The original film by Pavel Juráček, loosely inspired by the third book of Gulliver’s Travels, offers an anti-utopian vision of a country which is strangely familiar to Czech viewers. At the same time, it is a deeply personal piece of work. The author connects a political allegory and lyric layers.

The decadent order of the Balnibarbi society and the adventures of Gulliver correspond with the Czech experience of early socialism: the citizens look up to a leading figure under whom there is nothing but darkness; the country runs according to ridiculous instructions given by the Academy for Inventors; formally, people are governed by a smug governor (resembling Vasil Biľak); there is a ubiquitous figure of a conspicuously inconspicuous cop. The presumably scientific ideology and monarchist authority are used to promote fallacies (for example when the king suggests that even sewing machines could be used as calculators, and asks the academics to “creatively develop” pulleys, levers and shaft wheels to add those to the sewing machines, it reminds us of Stalin’s cybernetic mistake). The regime punishes poets for writing poems “alienated from our heart and soul” and employs “People’s Militias” which kill a student from time to time (the violence against the youth reminds us both of the student protest in Strahov in 1967 and victims of the August 1969 demonstration; the scene in which the students carry their fallen classmates also reminds us of Jan Palach). The mock justice system offers a place to a “judge from the common people” in a folk costume: “I am just an ordinary woman… And they call me out of nowhere to come and to sentence people, even to death; this really gets one thinking…” The variety show-like execution is accompanied by both a brass band and a gymnastics event (even in the darkest times, the regime still organized Spartakiades), and Vilma, volunteer Seid’s wife, remembers the lantern processions organized when she was young. People are wary of foreigners; they are interested in foreign opinions but cannot imagine crossing the border. The citizens repeat a banal sentence which the king says in his New Year’s speech every year, and they become hopeful when it seems to them that the accents in the word “sun” have changed.

Since the “shadow-like”, unauthentic lives of the Balnibarbi are contingent on the Laputa cult, Gulliver cannot find authentic life even in Laputa itself: there is a cult of an absent king, the minister of ploughing is a gardener, and the princess dreams of living among the common people. The mysterious structures of power, guarded from the “bottom” with terror, habits, good will and fear of knowing, prove to be piffling on the “top”. Yet the subjects are not happy with the reveal because they cannot live knowing heaven is indifferent – they would lose their purpose in life as well as their hard-earned personal dignity.

Juráček’s scepticism does not spare the opposition either. The conspiring students also need to believe in an authoritative figure. They think they have found it in the prince Munodi. They see him as a chance for a reform, and they too cannot cope with the loss of their illusions. The poet remains a tragicomic role.

Case for the New Hangman (Případ pro začínajícího kata) is, among other things, a film about the methods used for bamboozling people, making them passive, so that they are not only unable to organize their liberation but even unwilling to do it. It is a society building a totalitarian regime, driven by inertia and even by the feeling of living fulfilled lives, even though it goes downhill: “Listen, Vyskoč, is the watch going backwards, or is it just me? – But he said: Why do you have to scrutinize it like that – is it not enough for you that it ticks?” Case for the New Hangman outstrips other allegories of the time with its poetics and the important line of the personal, romantic story. Juráček wrote that what excited him about it was to bring a childhood world to life. He did not want simply to be juicy in a backhanded way; he would not settle for a mere satire. Balnibarbi is a dream mirror of Gulliver’s conscience; he looks for himself in the fairy-tale land. He goes through his 30-year crisis and gets lost in agonizing memories. He is full of remorse for the drowned Markéta whose face he sees in many Balnibarbi girls; he constantly talks with this ideal beauty of his, yet wakes up next to the voluptuous Dominika, an archetype of a prostitute, every morning. The story is therefore about a bad political conscience as well as individual, metaphysical, and erotic ones: “Maybe she hasn’t drowned, Mr. Gulliver,” says Niké, “maybe it was just you getting afraid. Maybe she is still alive. Maybe that you started crying at the time because you suddenly realized that she will never be what you would like. Maybe she is alive and happy and does not know that she is supposed to be drowned. Mr. Gulliver, that Markéta of yours is just what you wanted her to be – dead!”

The project working title, The Land of Kind Fairies, precisely depicts the archetypal way of addressing the audience used by Juráček: a combination of a fairy-tale, kindness, and fiction. The initial story is familiarly Czech from the very beginning. The landscape with a village chapel is “generally Czech” (Kučera). The ancient, familiar architecture of the Balnibarbi capital city with its cobbled streets, cathedrals, and vaulted ceilings inside tells us that Balnibarbi used to be a thriving country, possibly not that long ago. In Laputa, Gulliver finds typical Czech squares, streets, a tower. Several times, the viewer is surprisingly beguiled by the subconsciously familiar motifs, such as the dressed hare known from Alice in Wonderland. The fiction world unexpectedly offers several characters known from the audience’s world and time: Charles de Gaulle, Gagarin. There is the man with the cat from Juráček’s Joseph Kilian among the condemned people.

Similarly to Franz Kafka’s prose, both Laputa and Balnibarbi shock with their everyday banality; with the depressing yet common mess in which people are moving around with dignity, some of them still with the aristocratic routine of polite gestures. Lemuel climbs up a cluttered tower in Laputa. Where he expects a magical space, he finds only collapsed fragments of the old times, seen almost like through a young boy’s eyes. Lemuel himself is dressed in a featureless way, as a white-collar character. By incorporating the dream-like, surreal, fanciful motifs unto an informal everydayness, Juráček manages to create an atmosphere of disturbing uncertainty and intimate closeness at the same time.

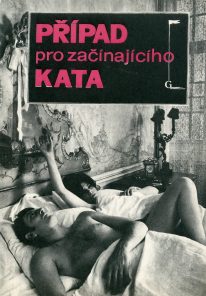

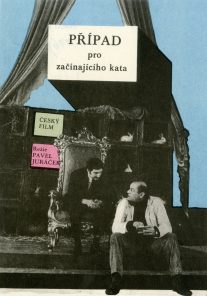

The informality of his vision is accented by the classical format and the black-and-white colouring. Cameraman Jan Kališ keeps the story realistically sober, as if we were simply observing it, with only a few deviations into the surrealistic (Markéta as a slightly brightened entity within the historical architecture; slow motion or hectic capturing of certain dramatic scenes). The atmosphere is further enhanced by Luboš Fišer’s music – by passages offering fairy-tale-like melodic comfort, orchestrion-like playfulness dominated by the piano, army-like briskness, and a mysterious song sung by a children’s choir: “Above the land of wolves, above the rocks of scorpions, Gloria Hallelujah…”

The story is divided into twelve chapters – into a rosary of episodes, not that different from picaresque novels, which leave the main protagonist seemingly untouched. The “discausal set” (Kučera) of causally unlinked, to a certain extent autonomous blocks, offers the viewer a wide intellectual and emotional space for associations, deductions, and personally intimate interpretations.

Case for the New Hangman is the best of Pavel Juráček’s (1935–1989) lifework and one of the best of the Czech New Wave and Czech cinematography in general. It is a synthesis of the author’s multiple talents, tendencies and efforts, as well as a synthesis of the European cultural memory – Jan Kučera finds it linked to the mediaeval folk theatre structure, but we can also see it as a tribute to baroque, to picaresque and humanist novels, novels of the Enlightenment, highly romantic stories, fairy-tales, surrealism, and absurd theatre. In the context of the Czech film industry, it is a synthesis of the sensually lyrical mode and the irony of those intellectually rational.

But Case for the New Hangman was shot too late to become internationally renowned like other films from the Czech New Wave. The film was almost unknown abroad (the new management of the Czechoslovak film industry no longer sent it to festivals); yet it was seen by about 28,000 Czechoslovak citizens. It was screened by film clubs till the end of 1975 (and even longer in Slovakia), as if by a miracle, and later was screened at least occasionally. It was therefore one of the very few available samples of the Czech film industry of 1960s in the darkest Normalization era; and in the narrow circles of club audiences, it was considered a cult film for a relatively long time.

Jaromír Blažejovský

Case for the New Hangman (Případ pro začínajícího kata, Czechoslovakia, 1969), director: Pavel Juráček, screenplay: Pavel Juráček, director of photography: Jan Kališ, music: Luboš Fišer, editor: Miroslav Hájek, cast: Lubomír Kostelka, Pavel Landovský, Klára Jerneková, Milena Zahrynowská, Luděk Kopřiva, Slávka Budínová et al. Filmové studio Barrandov, 103 min.

Bibliography:

BK [Luboš Bartošek], Případ pro začínajícího kata. Filmový přehled 1970, no. 28.

Případ pro začínajícího kata. Filmový přehled 1990, no. 6.

Pavel Juráček, Případ pro začínajícího kata. Film a doba 14, 1968, no. 5, p. 235-248.

Oldřich Adamec, Gulliver v arcibiskupském paláci. Záběr 2, 19. 4. 1969, no. 8, p. 3.

Sláva Pek, Případ pro začínajícího kata. Kino 24, 1. 5. 1969, no. 9, p. 2–3.

Pavel Juráček, Případ pro začínajícího kata. Film a doba 15, 1969, no. 7, p. 382-386.

Senta Wollnerová – Pavel Juráček, Odsouzeni ke Gulliverovi. Filmové a televizní noviny 3, 17. 9. 1969, no. 17, p. 1.

Pavel Juráček, V krajině vlídných bludiček. Ed. Miloš Fikejz a Zuzana Vranovská, 199. ZO Svazarmu, Praha 1989.

Stanislav Ulver, Případ pro začínajícího kata. Dramatické umění ’90, no. 1, p. 130–132.

Jan Kučera, Variace na téma z Jonathana Swifta. Dramatické umění ’90, no. 1, p. 133-148.

Pavel Branko, Fenomén aj výstraha doby. Dialog 1990, no. 11, p. 5.

Jaromír Blažejovsky: Příběh Lemuela G. Kino 48, 23. 2. 1993, no. 4, p. 31.