“And the silence was not stilled.”

Arnošt Lustig, “Darkness Casts No Shadow”[1]

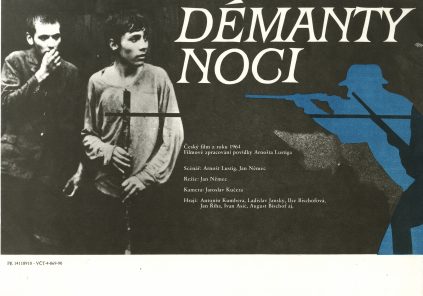

This film about two boys fleeing a death transport – or rather about complete human degradation, humiliation, the animalistic fear of death, the force of power, dictatorship, and ideology, as well as the desire for life and freedom – Diamonds of the Night (Démanty noci) is one of those cinematic masterpieces that is not easily forgotten. Its forceful moments accumulate over time, never letting the viewer relax, just like the hunt for the main characters never lets up. Shots overlap, stack, and multiply, leaving behind an indelible mark. Murmuring, whispering, breathing. Breath, between sound and silence, the signal of life and the foreshadowing of death. Rhythmically regular, fitfully pulsating. Terrifying ritual, disturbing hallucinations.

The film’s power can be attributed to director Jan Němec’s modernist conception – the film is structured around the blending of temporal levels, a complex shaping of the characters, simple plot development, a lack of action, minimal dialogue, and the emphasis on events beyond the film frame. These techniques are partially rooted in Arnošt Lustig’s short story “Tma nemá stín” (Darkness Casts No Shadow) on which the film is based, however, the film achieves unprecedented originality mainly thanks to its (audio-)visual component.[2] Lustig’s writing contains many descriptions and evocative settings, it is rich in visual details and atmospheric compositions, yet the conversion into film language is an unparalleled achievement. This is particularly due to the varied range of cinematographic techniques, methods, and ideas employed by cameraman Jaroslav Kučera, who maintains perfect control over the cinematic medium, the fictional world of the film, and the audience.[3] The unforgettable breathing certainly does not belong only to the characters, there is also the breathing of the image, (specifically) of the film material itself. The image, its lines, abstract patterns, textures, structures, spaces, surfaces, and contours, its grains and its frame, are constantly pulsating, gently shaking, inhaling and exhaling. The rhythm of breath, heartbeats, and the boy’s flight through the landscape is dramatically composed by the sophisticated and precise editing of Miroslav Hájek, “a virtuoso of the frame”.[4] The precisely timed pace of the images further accentuates the characters’ surroundings, which are muddy, dirty, slippery, or covered with dust.[5]

The camera is not just a tool of observation, an instrument of the gaze watching this struggle for life, but also one of the film’s protagonists: it does not pursue, but is rather pursued; it does not record, but rather participates. Intense close-ups, extreme proximity. The film strip is not only a witness, but also the “skin” of the filmic body, a highly (light-)sensitive medium, into which all the fear, exhaustion, and panic of their experience is inscribed. This anthropomorphisation of the camera completely eliminates any space between the viewer and the story, any critical distance, any space for empathy. Instead, the viewers are “sewn” into the story, getting out of breath and disoriented together with the characters, subject to the claustrophobia of this absurd situation, of time and space.

Supported by the film’s distinctive sound component (supplied by František Čech and Bohumír Brunclík), which often accentuates the sound of breathing, the breath of the characters and the breath of the film material merge, creating a harmony, a polyphony that synthesises the absurdly escalated dualities, paradoxes, and ambiguities that arise especially at times of madness. The impressive personalisation of the technical means together with the unusual awakening of worn down film characters thus give rise to a profound tension between corporeality and disembodiment both in the diegetic world and beyond it. Murmuring, whispering, breathing. Rhythmically regular, fitfully pulsating. The extreme evocation and authenticity of experience is not only the result of the well thought out and functionally structured camera operations (e.g., the shaking camera that follows the characters in great detail as they run through the forest or the long static shots that allow insight into the characters’ progressively fading past), but is the product of highly conceptual creative work on all levels: from the choice of film stock to the lighting to the post-production effects. The austere image that documents the story is increasingly disrupted, questioned, stylized, and formalized; the textures and the film material itself increasingly emerge from the image. The initially realistic story takes on hallucinatory dimensions, its fictional world falls apart, as do any ethical limitations. Terrifying ritual, disturbing hallucinations.

Paradoxically, one of the film’s main atmospheric and narrative means is colour, even though it was shot in black and white. Kučera perceived black-and-white film stock as “colourful” material, whose colour is only eliminated by the grayscale. He considered black-and-white film to be an (extremely) stylised variant of colour film, a variant that is always aesthetic and aestheticised. In both the individual photographic images as well as in the overall conception of the film’s visual component, stark black and white surfaces regularly alternate, while shades of gray are significantly reduced.[6] The image is ultimately dominated by a deep blackness, similar to the time period it depicts. “Is everything lost in the dark?”[7]

The two narrative levels, the real and the unreal, are governed by completely different pictorial and chromatic concepts. The escape scenes were filmed without artificial lighting on Ultrarapid stock, a highly sensitive, coarse-grained film material typically used for news reporting, and the negative was processed using special developers. The image therefore has very high contrast, allowing it to reflect the darkness of the forest and to achieve a certain plasticity, a haptic quality. Contemporary criticism comments on the raw, almost documentary quality of the image: “The raw photography evokes an impression of authenticity, such that the viewer has the impression that he is watching a compilation film, edited together from various pieces of documentary footage.”[8]

The film’s sense of dynamism and naturalism was enhanced by Miroslav Ondříček, who in some ways served to counterbalance Kučera’s aestheticism. The prevalence of dark spaces emphasises the dramatic nature of the situation as it steadily intensifies, attaching itself to the heroes and pulling them into its centre. “Death was like a quagmire now.”[9] When operating on the level of dreams, visions, and memories, the image loses its strong contrasts and sharp contours due to the use of positive or expired stock, which adds emphasis to bright, illuminated areas – which in turn results in a reduced sense of drama, inducing a suggestive feeling of warmth that also approaches the faded, vague nature of memories and deviated states of consciousness, but which offer no consolation.

This erasure of bright lines and disruption of the illusion of three-dimensionality creates a feeling whereby objects lose their relevance, reality and its traces disappear, and the image transforms into a mere interplay of geometric structures with minimal differences. The cameraman’s son, Štěpán Kučera, has drawn attention to the specific spatial construction of these dream images, in which the two-dimensional spatial composition or, conversely, depth and perspective are alternatively emphasized. Either way, movement within the images is minimised (in contrast to the nervous and hurried movements of the escape scenes), and “architectural fragments are composed like creative still lifes, whose relevance to the figures is out of balance.”[10] The shots of decrepit buildings and crumbling plaster further contribute to this impression of a fading reality. The feelings of ambiguity and uncertainty are supported by means of an experimental use of sound that works with actual noises of the city. Anxiety once again returns to the image. Neither remembrance nor illusion offer salvation.

The pictorial reflection of a disintegrating reality, which seems to release us from the force of gravity, is even more powerful in scenes where it is also accompanied by a disintegration of temporality, just as the main heroes have “lost all sense of time”.[11] Fundamental to this deformation of the temporal plane – the deformation of linearity and causality being just one of its components – is the film’s work with luminosity, reflections, and illumination as specific formal elements inherent to the visible and coloured objects. Cinematographer Henri Alekan has described the duality of “light” thus: while direct, cosmic light escapes our power and always carries with it a temporal determination, light that is by contrast artificial, indirect, and diffused eliminates time and results in a suspension of the perception of temporal structures. The escape scenes employ direct and modulating light that possesses temporal qualities, such as that described by Alekan in his book Des Lumieres et des ombres (Of Lights and Shadows): “in their form, position, and density, the depicted shadows become a materialisation of temporal data that allows us to perceive the abstract dimension of its flow.” [12] By contrast, in the dream scenes, Kučera uses diffused light, which lacks a clear source (though presumably located within the space), which brings them closer to timelessness. Darkness or light, which casts no shadow; the only shadows are the boys’ bodies.

The sense of timelessness is also amplified by temporal disorientation, the alternation between the present and the past, reality and imagination, presence and absence, movement and immobility. “He’d got to kill her. Everything else died away within him. (…) He felt dizzy. His eyes fell on the table with its red linen cloth with a white fringe. But he saw the rest of the room too. Chairs with square carved backs. A blue dresser with yellow mugs and a bread tin. A china coffee mill hung up on the wall, with a wooden handle. His head was reeling. The only thing he could hang on to was the stick and the thought that he was going to kill her.”[13] The famous scene from Diamonds of the Night in which a woman is (possibly) killed was shot with a handheld camera, the action was repeated and re-filmed several times with minor shifts and is intercut with shots of the nearly static protagonist and images of the interior. Movement (or the lack thereof) and the collage technique are thus transmitted to the narrative plane and underpin the (non-)linearity of the narration – fragments of the present, the past, and the (hypothetical) future can be assembled in a non-traditional fashion, not necessarily according to chronological or causal links. Individual shots become multivalent representations, inviting associations, moving away from reality and returning back to it through the subjective response of the viewer. The denial of natural motion due to the film’s collage-like form, the repetitive nature of the sequences, and the destruction of narrative linearity constantly unsettle the viewer while at the same time opening up a space for imagination that allows for the necessary reconsolidation.

This film, which communicates subliminally through a distinct and constantly accentuated materiality, and the level of audio-visual mastery that it achieves without becoming a flamboyant, emptied gesture or ornament, is a very powerful, raw, authentic but at the same time aesthetically sensitive spectacle – very risky material for restoration. Its breath could be suffocated. The subtle shimmering, the hardly perceptible differences, the relationships between surface and depth, or light and darkness, are so fragile that even some prints made from the original film material have managed to wipe them away, thereby weakening the film’s overall impression. Fortunately, this is not the case with this digitisation: the open ending points to immortality rather than death, the breath of the image has been preserved, as well as its murmuring, its whispering, its regular and fitful rhythms, its terrifying ritual and its disturbing hallucinations.

Kateřina Svatoňová

Diamonds of the Night (Démanty noci, Czechoslovakia, 1964), director: Jan Němec, screenplay: Arnošt Lustig, Jan Němec, director of photography: Jaroslav Kučera, editor: Miroslav Hájek, cast: Ladislav Janský, Antonín Kumbera, Ilse Bischofová, August Bischof, Ivan Asič, Jan Říha et al. Filmové studio Barrandov, 67 min.

Notes:

[1] Arnošt Lustig, Darkness Throws no Shadow. In: Lustig, Diamonds in the Night. Prague: Artia 1962 (translation by Iris Urwin), p. 178. NOTE: All quotations from the story “Darkness Casts No Shadow” are taken from this publication. There is also an expanded version of the story published separately as a stand-alone story/novel, in (a different) English translation: Arnošt Lustig, Darkness Casts No Shadow. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1985 (translation by Jeanne Němcová).

[2] Jiří Cieslar even labeled Diamonds of the Night as “pure film”. Jiří Cieslar, Snové tělo Démantů noci. In: Cieslar, Kočky na Atalantě. Praha: NAMU 2003, p. 446.

[3] The second camera, as well as the independent shooting of some scenes, was taken on by Miroslav Ondříček, assisted by Ivan Vojnár.

[4] Jiří Cieslar, Když si film začne o něco říkat: Rozhovor s Janem Němcem. In: Cieslar, Kočky na Atalantě. Praha: NAMU 2003, p. 461.

[5] Loosely based on various descriptions of the characters’ surroundings in the story “Darkness Casts No Shadow”. Lustig, Darkness Throws no Shadow.

[6] This black-and-white stylisation actually anticipates his later structural and material film experiments – multivalent counterpoints, the sharp alternation between two story levels, and the contrasts within individual scenes and images function almost like “flicker effects” in underscoring the perception that they constantly betray.

[7] The opening epigraph to “Darkness Casts No Shadow”. Lustig, Darkness Throws no Shadow, p. 108.

[8] Ivan Bonko, Útěk do tmy. Práce, 2 October 1964.

[9] Lustig, Darkness Throws no Shadow, p. 143.

[10] Štěpán Kučera, Porovnání obrazové koncepce v hraném a dokumentárním filmu. Magisterská diplomová práce. Praha: FAMU 1995, p. 8.

[11] Lustig, Diamonds in the Night, p. 178.

[12] Henri Alekan, Des Lumieres et des ombres. Quotation translated from the Czech translation of the original in the bachelor’s thesis: Marek Loskot, Koncepce světla v knize Henriho Alekana O světlech a stínech. Bakalářská diplomová práce. Brno: Masarykova univerzita 2009, p. 44.

[13] Lustig, Darkness Throws no Shadow, p. 152.