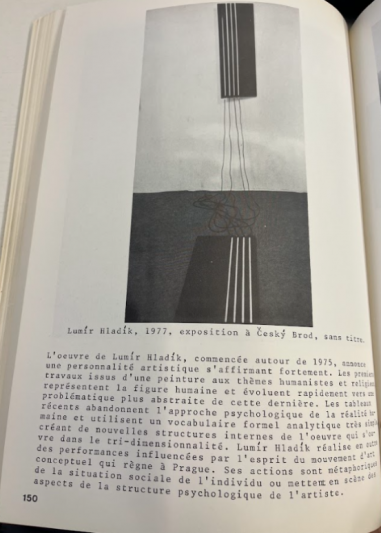

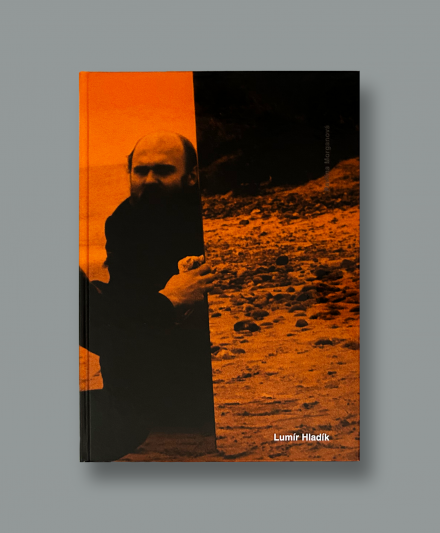

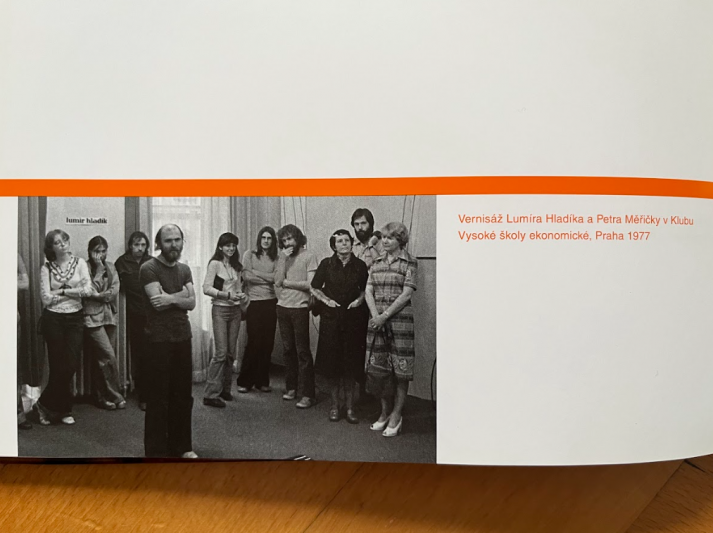

Lumír Hladík has lived in Canada since 1981, creating artworks on the borders of concept, action art, drawing, and video. The roots of his work, however, reach back into the 1970s, when action art was being defined on the fringes of the Czech art scene. Hladík was part of a circle of body artists that also included Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch, and Karel Miler, but the informal, low-key nature of his performances brought him closer to the work of his friend Jiří Kovanda. Hladík was one of the few to document his performances – which took the form of temporary interventions in the landscape – on film. This footage, originally shot on 8 mm colour film, was recently digitized at the National Film Archive and supplied with explanatory texts by the author.

These texts were taken from Pavlína Morganová’s book Lumír Hladík (SVIT Gallery, Prague 2011) with the kind permission of the author.

Ritual Murder of a Stupid Smirk (Rituální vražda pitomého úsměvu)

This performance was one of the few pieces of action art to take place in Hladík’s apartment. It betrays the artist’s interest in the everyday symbolism of small artefacts that can provoke him so much that he decides to destroy them. This was the fate that befell a wooden statuette of a jester exhibited in the shop window of a toy store near the apartment where Hladík lived at the time.

Czechoslovakia

1976

Anonymous Remained Anonymous (Neznámý zůstal neznámý)

Lumír Hladík often set his events in forests – both in totalitarian Czechoslovakia and in Canada. The character of the cultural landscape, or, in contrast, the Canadian wilderness, influenced the topics Hladík explored. In this event, Anonymous Remained Anonymous, he made a futile attempt to de-anonymise a tree.

Czechoslovakia

1977

My Personal “Eternal” Vector (Můj osobní „nekonečný“ vektor)

“I decided to become the proprietor of a cosmic vector.” On the basis of this decision, Lumír Hladík prepared an event: he placed a milestone and a sign in the landscape, both bearing the symbol of infinity. Both objects remained at the location for the following twenty-five years. Hladík was already living in Canada when his friend Petr Soukup shot the location footage. Soukup also made film recordings of all of Hladík’s previous performances.

Czechoslovakia

The event took place in 1977. The film documentation was made in the second half of the 1980s.

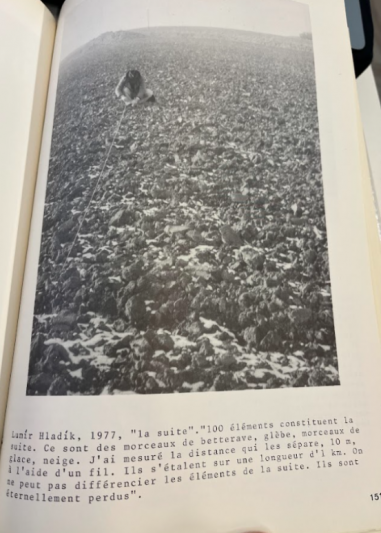

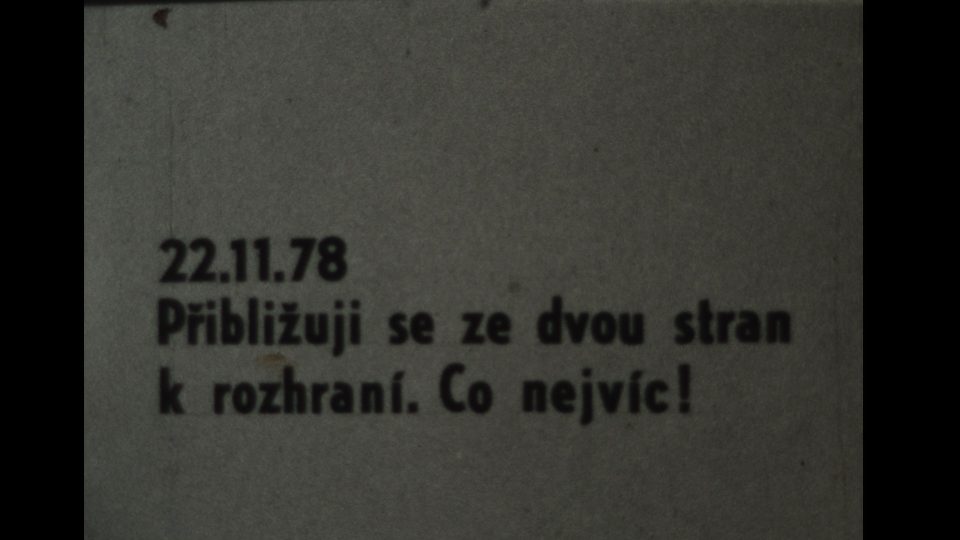

Boundary; A Question Without Answers (Hranice; otázka bez odpovědi)

Hladík’s seemingly simple events build on deeper considerations, often arising from conversations with friends and artists, who thus searched for an escape from the limited thematic repertoire of totalitarian society. Realising artistic performances was, to an extent, an empirical test of these conversations. For Hladík, the landscape served as suitable terrain for these artistic experiments in the form of subtle, personal interventions.

Czechoslovakia

1977

I Reduced the Diameter of Earth (Zmenšil jsem průměr Země)

In the 1970s and 1980s, art performances by Czech artists took place outside the public sphere of art. Their outreach was restricted to the community, or, as in the case of Lumír Hladík, was almost exclusively personal. Perhaps this is why Hladík was provoked by the idea of a “monumental” act – nothing less than an attempt to reduce the diameter of the Earth.

Czechoslovakia

1977

The Never Boulder (Už nikdy tenhle balvan)

In the second half of the 1970s, Lumír Hladík realised several events in the Central Bohemian Region, where he grew up. In retrospect, however, he says of his choice of landscape that it was a mere tool, like when you grab a piece of paper to draw on. In film documentation of his events, therefore, the landscape remains anonymous to a certain extent, and it is only the performer’s trajectory that draws out a theme. In this case, Hladík attempted to “put an end” to a rock that had provoked him since childhood.

Czechoslovakia

1978

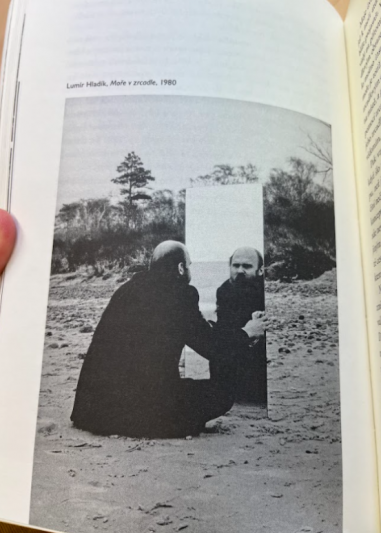

The Mirrored Sea (Moře v zrcadle)

“One day, I realised it had been two years since I had last seen the sea. The sea was always a symbol of freedom. I decided that two years is long enough (emotionally) for me to set out towards the sea again with the aim of ‘not seeing it’. I asked my friends to drive me – blindfolded and carrying a large mirror – to the shore of the Baltic Sea in East Germany.” It was thanks to this event that Lumír Hladík’s Czechoslovak works could be discovered, completing our view of action art of the period and its unique relationship to film.

Czechoslovakia

1980