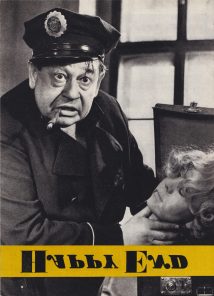

Following the success of Lemonade Joe (Limonádový Joe, 1964), Oldřich Lipský wanted to make an Italian co-production with foreign actors filmed in attractive locations such as Capri, Mallorca and the Alps. Even though he eventually couldn’t join forces with Italian producer Moris Ergas, Happy End (1967) is an exceptionally ambitious film in the context of Czechoslovak cinema. Not just thanks to its production value, but also thanks to its experimental form of narration.

“In Happy End, the story starts at the end. The film begins with the execution of a man who cut his unfaithful wife into quarters and took her away in a suitcase. I think the audience will have fun. But I also think that Happy End isn’t just a gratuitous comedy, I think it has scenes which will make the audience think whether they want to or not.”[1]

Upon an unwritten agreement with the audience, most live-action films respect certain narrative conventions. Consequences are preceded by causes, answers by questions, endings by beginnings. In the 1990s, terms like “mind-game films” and “puzzle films” started to describe films that don’t follow such rules. In these films, classic narrative methods are substituted by complex narrative structures with many deliberate gaps, blurred lines between reality and imagination, unreliable narrators and ambiguous meaning. The story can go in several directions at once or comprise several stories in one, taking place on different planes of reality or in different timelines. The Aristotelian story structure (beginning, middle, end) with a linear chain of causes and effects is usually not applied. In such films, commonly used cognitive schemes helping us to piece together many fragments to discover a coherent plot just aren’t enough. [2] Predecessors of films designed to confuse the audience can be found all over the world (for instance Resnais and Robbe-Grillet’s film labyrinths with no way out). One such film, whose intellectual requirements on the audience surpasses films such as Fight Club, The Sixth Sense and The Prestige, was made in Czechoslovakia fifty years ago. Just like Memento (2000), Bakha satang (2000), Irreversible (2002) and Five Times Two (2004) some thirty years later, Happy End (1964) by Oldřich Lipský and Miloš Macourek bends the conventional rules to conform to its own reversible world. It’s a manifestation of extraordinary playfulness and simultaneously the unwillingness to play with the others. But the film, perceived in the light of more serious production from the Czechoslovak New Wave as a banal “joke”[3] for one-time entertainment, is elaborate and multi-layered and deserves at least the same amount of attention as The Firemen’s Ball (Hoří, má panenko, 1964) and Markéta Lazarová (1964), released in the same year. [4]

Francis Scott Fitzgerald had the idea to tell the life story of his protagonist in reverse already in 1922, when he published his story The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, widely known thanks to its film adaptation by David Fincher. But in this case, the atypical content was presented to readers in a classic form with a chronological order of events. It’s just that the protagonist isn’t getting older but younger. Experimenting with the form isn’t very prominent and instead of building a reversible film world, the author uses the standard chronology of the actual world. While Fitzgerald required the readers to accept only the reversed flow of life, the first collaboration of director Oldřich Lipský and writer Miloš Macourek reversed the entire fictional world along with the hero. Other examples of literary works with reversed chronology created before Happy End include for instance Goodbye to the Past (1934) by W. R. Burnett, The Human Season (1960) by Edward Lewis Wallant and Christopher Homm (1965) by British writer C. H. Sisson. The history of films starting at the end in our country dates back to 1898, when Jan Kříženecký played a short film at the Exhibition of Architecture and Engineering titled Žofín Swimming Pool (Žofínská plovárna) backwards, to great amusement of the audience. [5] Thanks to reversing the reel, the swimmers jumped out of the water. The same “prehistoric” gag is used also in Happy End, which claims its allegiance to the beginnings of cinema by its setting (early 20th century) and sepia tone reminiscent of old photographs. The movement back is also manifested in its artistic stylisation. According to Dutch ludologist Johan Huizing, a precondition to accept the rules of a game that we don’t know is a desire to play it. [6] The game framework in Happy End is set already in the opening credits. The first words to appear are “The End.” After that, the credits say “Central Film Rental in Prague Presented.” At a certain point, traditional credits are replaced by a mirror text that is subsequently reversed so we can readily read it. The opening scene of the film is puzzled together piece by piece during the entire opening credit sequence. The resulting image shows the decapitated head of Vladimír Menšík, which winks at us and asks for cooperation. The authors play a game and challenge us to take part in it (puzzling, a very popular activity, is once again used to “put together” the wife chopped into quarters).

Just like in the early years of cinema, Happy End uses the film medium as an attraction to entertain the public. The narrative flow stops several times and its integrity is compromised in order to offer the audience stimuli of an attraction nature inspiring awe and astonishment over the possibilities of the film medium (for instance, the very graphic murder of the wife, several minutes of pulling biscuits out of one’s mouth and the aforementioned jumping out of water.). Despite the presence of a simple plot line, Happy End often comes across as a showcase of attractions used by the first cinema owners in their programmes. The requirements placed on the receivers of audiovisual content are, however, much higher than in the era of cinematography attractions. The alteration of narrative and attraction organisational principles prevents the perception exclusively through sense stimulation. Due to the reversed order, we have to constantly evaluate the images and sounds and actively think about them. [7] Similarly, the film doesn’t settle for a shallow comical effect, and its humour is much more sophisticated than the humour we know from early film comedies.

The film’s images and diegetic sound force us to think in reverse. Bedřich’s monologue, on the other hand, complies with the chronological flow of time. The constant alteration between these two modes of reception and retrospective matching of plot incidents with statements uttered earlier is relatively demanding attention-wise. Constantly going back to performed actions and uttered lines doesn’t mean that the film’s humour is incomprehensible. In a certain sense, Happy End works in both ways. The verbal humour is built mainly on incorrect word order, which often creates short Dadaistic formations (– Were you born? – Not at all!). In one direction, the sentences are humorous, in the opposite direction, they make sense. We can enjoy Happy End as a nonsensical film pun without any trouble. The palindromic elaboration of the literary original that enables the two-way perception of the film was probably created by Miloš Macourek, who repeatedly demonstrated his Dadaist playfulness and penchant for paraphrasing popular genres and wordplay in his poetic work and his long-term interest in the work of Alfred Jarry (Macourek was the co-author of the script for F.A. Brabec’s King Ubu (Král Ubu, 1996). The reasons of this devotion to wordplay, which in Happy End is equal to physical gags, can also be found in the long tradition of Czech verbal humour epitomised for many by Hašek’s gabby Švejk.

The film can be characterised by a number of small inside games, whether on the formal or content plane. At one point, the film is livened up by slow motion – a horse race is shown backwards and in slow motion. Once again, we return to the beginnings of the cinematograph, which was originally supposed to serve scientific purposes by helping to examine animate objects. Muybridge’s footage of a running horse is one of the emblematic early attempts to animate still photographs. The playfulness of the film is manifested in multi-level contrasts. Thanks to the rewinding, morbid scenes are not only funny (a head jumping back on a neck, limbs “sawed onto” the body) but also stand in an opposition to some romantic moments, which are on the other hand disgusting (pulling cookies out of one’s mouth accompanied by an inappropriate adjective “excellent;” Bedřich’s dreams about his beautiful past at a slaughterhouse.) Another dichotomy repeatedly arises between Bedřich’s and ours (normal) perception of the circle of life. In the absurd reverse world, the death of his father-in-law is joyful news and the birth of a child tragic. We have Bedřich the murderer and Bedřich the creator. The object of his actions is in both cases paradoxically the same person, his wife. By seeing the story with elements of a murder ballad with his own inverted logic, Bedřich justifies all crimes he committed. As the narrator of the story, he refuses any alternative interpretations that would make him the guilty party. His commentary de facto isn’t in direct contradiction with what we see, but it denies the universally valid standards of what is admissible and right. Does that mean that Bedřich automatically becomes an unreliable narrator who bends the truth to suit his personal interests? Or does he speak the truth in his universe? Due to the fact that he comments on events that already happened to him and should be dead, Bedřich could be a post-modern narrator standing above the story and realising the importance of himself as someone who narrates the story. Just like the first commentators at film screenings, he tries to explain the sequence of images to the viewers who could get disoriented. It seems that his commentary influences occasional stops in the films (description of individual items that Bedřich was “presented” in jail.) Accepting Bedřich as a commentator of moving pictures would mean giving the film another attribute inducing the spectator experience from the beginnings of cinema. If formal experiments destroy the narrative coherence, the objects in the mise-en-scène help the comprehensibility of the plot and the characters. But their function is also ambivalent. The painting of lovers at the wall could at one point foreshadow what could happen between Julie and Ptáček – if the film wasn’t shown backwards. In the reversed chronology, the hint becomes a confirmation of a known fact. On the other hand, the function of the newspaper with a peephole is unquestionable. With its help, Bedřich pretends to be a private investigator. Switching between various roles is a motif developed throughout the entire film. Opinions about the film’s characters based on the first impression are mostly misleading. Based on his refined vocabulary, not many people would expect Bedřich to be a butcher (and this kind of self-stylisation takes us back to the unreliable narrators). Ptáček is described by Bedřich as a treacherous villain but doesn’t act like one. He is merely the lover of Bedřich’s wife. This volatility in the perception of the characters based on available information (and the order in which it is presented) and the necessity to constantly alter one’s opinion about individual characters is a part of the game, whose rules are evolving constantly.

The authors resourcefully play with the sound. Words sometimes pointlessly describe what we hear (“click”) and act as intertitles in silent films; other times they describe what we see (“hand”, “head”, “leg”) and underline the action nature of some scenes. An example of an original usage of sound as a musical background can be found towards the end (i.e., the beginning) of the wedding ceremony when the sounds of kissing set the rhythm of the scene. Every listed example works with sounds differently than we’re used to – the sound doesn’t supplement the information presented by the images but doubles it. The playfulness of Happy End is also manifested in smooth transitions to musically stylised dance numbers. However, only the form is musical, not the content. Bedřich elegantly dances with the body of the murdered Julie; Julie, in an effort to hide her lover, frantically dances with Ptáček. The tango, danced later by Julie and Ptáček, is downplayed by mooing of cows in the background. These discrepancies have a comical effect and contribute to the perception of Happy End as a film whose driving principle is a deliberate reversal of logic known from standard live-action films. The links between the film’s comical effect and used narrative means could be summarised in a paraphrase of a quote by Charlie Chaplin: “Life is a tragedy, when lived from the beginning to the end, but a comedy in reverse.” [8]

Bedřich sees the confiscation of his property in jail as creating a socially just society in which everyone is equal because no one owns anything. The obvious political connotation of this situation, actually a literal representation of an anecdote popular during socialism, reveals another layer of Happy End. Its unrestrained playfulness disregarding the existing rules has almost anarchistic qualities. The closest thing to abstract meaningless declarations in the film is not surprisingly the communication of official authorities. In Happy End, Havel’s ptydepe language has a fitting film form. But it’s not malicious anarchism intended to destroy and harm, it’s an anarchism governed by a childishly impish desire to subvert the established order.

Scenes portraying revolt against the established order are mostly gastronomical, as was typical for this period. A year before Happy End, Věra Chytilová’s Daisies (Sedmikrásky, 1966) sparked outrage at higher places because it included scenes in which food was wasted (this was also used as the official explanation for the film’s limited distribution). [9] As an ironic commentary to disapproving reactions on wasting food, Happy End includes anti-consumerism scenes. The characters don’t actually eat the food but produce it. The ensuing self-production system changing the consumer directly into the producer is a playfully exaggerated but biting example of what a communist utopia could look like in reality. Happy End is a unique film not only in Czechoslovak cinema. By implementing its own set of rules and disregarding the existing ones, it represents a unique conversion of Dadaistic poetics to film. Just like many New Wave filmmakers, Oldřich Lipský and Miloš Macourek used games as a distinctive method of approaching reality. The time definition of the most expressive displays of playfulness in Czechoslovak cinema could tempt one to perceive games as a phenomenon bound to the culture of the 1960s, but as several examples mentioned above indicate, probable sources of Happy End’s playfulness are far older than that. For political reasons, it was impossible to make similarly playful films for two decades after Happy End was released. It seems that, in addition to a creative tandem like Lipský – Macourek, contemporary Czech cinema lacks the courage to fully give itself over to game.

Martin Šrajer

Notes:

[1] Oldřich Adamec, Dvanáct nových rolí Vladimíra Menšíka. Kino 22, 1967, no. 10 (18th May), p. 11.

[2] More detailed to the concept of mind-game film see Thomas Elsaesser, The mind-game film. In Buckland, Warren (ed.), Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell 2009, pp. 13–41.

[3] Such elitist classification of Lipský’s comedy came from Jan Žalman. Umlčený film. Vimperk: KMa, s. r.o. 2008, p. 253.

[4] In an interview with Antonín J. Liehm, Oldřich Lipský complained about an ignorant view of critics on his comedic production because of the comedic genre itself.

Ostře sledované filmy. Praha: Národní filmový archiv 2001, p. 174.

[5] Sometimes also named Výjev z lázní žofínských, Zdeněk Štábla, Český kinematograf Jana Kříženeckého. Prague: Československý filmový ústav 1973.

[6] Johan Huizinga, Homo ludens: O původu kultury ve hře. Podlesí: Dauphin 2000.

[7] With certain simplification, we could apply the concept of intellectual attractions synthesising intellectual and visceral film experience on Happy End. Radomír D. Kokeš writes about it in relation to contemporary Hollywood action films: Kinematografie intelektuálních atrakcí: jistá tendence blockbusterového filmu. Cinepur 59, Sep-Oct 2008, p. 25–31.

[8] Chaplin allegedly said “Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long-shot.” See Jeffrey Vance, Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema. New York: Harry N. Abrams 2003, p. 56.

[9] The interpellation of MP Jaroslav Pružinec in the Czechoslovak National Assembly is now infamous. 15. schůze. Poslanecká sněmovna Parlamentu České republiky [online]. [quoted 2017-02-08]. URL: <http://www.psp.cz/eknih/1964ns/stenprot/015schuz/s015015.htm >.