“It was late Saturday evening when I saw a young girl in the centre of Prague. She was dragging a worn suitcase but she didn´t seem to hurry anywhere, or that she wanted anything of anyone, and clearly she was no prostitute either. She seemed lost. But also that she didn´t mind it very much. I was curious. I started chatting with her and talked her into going home with me.” These are the words Miloš Forman uses in his autobiography[1] to give us an idea of where the initial concept for Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky) came from.

The girl worked in a textile factory in North Bohemian Varnsdorf, a town with many flaws, with one of the biggest being the lack of men as compared to women. The young lady thus deemed herself very lucky when she met an engineer from Prague who, after having spent a night with her, invited her to his home, to a city. However, she soon became disillusioned with men and the life in Prague when it turned out that her suitor had given her a spurious address. Forman then, together with the proven duo of authors Papoušek-Passer, turned her bitter experience into a tragicomic story of young love and unfulfilled desire, especially the desire for freedom.

“And the big love made my hair grow long and I have become a rowdy…” sings a girl leaning against the wall with an admirable passion during the opening credits, accompanying the lyrics of a favourite hackneyed song by the guitar. The scene, which resembles to Forman´s medium length pseudo-documentary film Audition/Talent Competition (Konkurs, 1963)[2] introduces us into the world of teenage love bamboozling, but also shows unrestrained youthful energy, a need for their, perhaps imperfect, but authentic voice to be heard. The symbol of rebellion against the deeply-rooted paradigm and official culture here is the guitar that the camera clings to again in the first scene of the film, taken in one of the rooms in the girl´s boarding school.

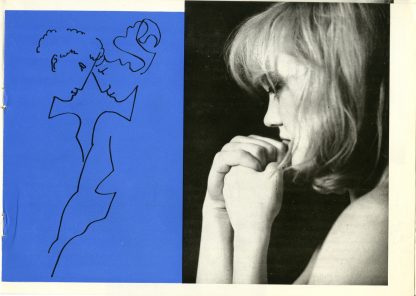

The “guitar symbolism” later acquires an erotic dimension when Milda (Vladimír Pucholt), in the process of getting closer with sixteen-year-old Andula (Hana Brejchová) impertinently compares the curves of his cursory romance to the guitar by Picasso. At that moment, while being alone in the room (with successfully closed blinds, at last!), the two young people are the closest to each other. This is the only time in the whole film when they don´t have to submit to other people´s looks or commands. The intimacy is also induced by the composition of the scene which is completely filled with two overlapping naked bodies sunk in duvets during their post-coital dialog, the two furthest refuges from the outer world.

The third time the guitar gets engaged in the story is in the last scene of the film. This time, however, only as a sound track. Andula´s return to her routine work in the factory is underlined by a guitar variation of Prelude C major by Bach´s Well-Tempered Clavier. In this scene, the instrument is not a symbol of liberation, unlike in other scenes, but of sadness and reconcilement, a subdued desire for an independent life.

Adding new layers of motives on particular objects links individual segments of the storyline and contributes to the film´s constricted nature. Right after the guitar scene during the first minutes of the film, our attention is caught by the ring decorating Andula´s hand. The girl in loves looks up to it as to a symbol of happy tomorrows that she is going to spend by the side of beloved Tonda. But Tonda proves to be a self-centred halfwit who first fails to arrive at the arranged meeting in the forest (at the tree marked by the tie that Andula later arrives in Prague with) and then seeks his loved one only to aggressively claim the ring back to which Andula responds with tears and cry.[3]

From this moment on, the ring is no longer a symbol of happy future, but of humiliation and restriction. A similar source of humiliation during a dance party becomes a wedding ring belonging to the bespectacled reservist Maňas (Ivan Kheil). In an attempt to conceal his marital status from the timid girls he takes the shining circle off his finger, loses it and then pursues it on all four amongst the legs of dancing couples and sitting ladies.

While we can sympathize with unhappy Andula thanks to the empathetic portrayal of her situation,[4] the look at the middle-aged man, eagerly chasing a tiny round object, is amusing. Not only because of the embarrassment of a man. Forman uses his smallness and clumsiness also to ridicule the Czechoslovak armed forces (just like at the beginning of the film where the soldier in a snow-covered forest, ineptly suggests Andula to listen together to the sounds of grunting deer) and the institution of marriage, limiting one to unfold (as we can also see during the last part with Milda´s parents).

Paradoxically, marrying one of the members of the newly established garrison is the thing, which is supposed to bring happiness to the women working in the textile factory in mainly feminine town of Zruč nad Sázavou (where the setting has moved to from Varnsdorf). At least, this is what the army deputy (Jan Vostrčil) and the workshop master Pokorný (Josef Kolb), men in high posts, in advanced and old age respectively think, while, with lecherous fondness, label the girls as “flower buds” waiting to be kissed and hugged. Both men mistakenly presume they understand the socialist youth and are thus qualified to think and make decisions in their stead. So it comes as a no surprise that the young heroes find it hard to assume responsibility for their words and actions, to stand their ground.[5] Since they have always had to subdue to someone else’s idea of how they should behave, they never had the chance.

Making contact between the blooming girls and the withered reservists, detached to the town against their will instead of being the brave defenders of their homeland, should take place during a dancing party in the local community centre. A strained, top-down directed get-to-know-you party however doesn´t unfold as planned, regardless the permanent smile of Pokorný, who embodies the unrelenting party´s supervision in the role of a musical conductor of a kind (the same role of an overseer, responsible for smooth manufacturing process and working socialist system as such, Pokorný also fulfils in the textile factory, where he walks among the women and checks that they are doing their job well; the goals of fulfilling the plan and seducing in order to procreate are put at the same level).

Both camps exchange silent looks which are a mix of embarrassment, lack of understanding and doubts, sometimes accompanied by astonishment or disgust. Neither the brass band music plying the song Hej, panímámo seems to be an effective way of speeding the dating process up because it contrasts with the dynamic title song, while the text corresponds to the obscene point of view of the older generation and their rigid ideas of young people and love. The formality of the entire event is increased by the feeling of subjection penetrating the whole film, creating almost tangible embarrassment, in the staging of which Forman was second to none. The individuals are not having a spontaneous fun, but are mere fulfilling a pre-set purpose, having their personality sacrificed to the system.

Only thanks to the rejection of the compulsory programme and escaping from the hall Andula meets her peer, emotionally just as clumsy, but more experienced piano player Milda. However, the liberation (sexual) doesn´t go well either and the satisfaction it brings is only temporary. After the scene, in which Andula tries on Milda´s coat (and figuratively also the life under his protection) follows a quick cut back to the factory where the women once again become insignificant cogs in the huge manufacturing wheel, mechanically and rhythmically performing the work they have been assigned.

Andula´s romantic dream of living the life side by side with her spouse, which she has adopted as her ideal due to the social indoctrination, falls to pieces shortly after her arrival in Prague where she doesn´t get the warm welcome she has been expecting. On the contrary, she finds that her role in Milda´s life is just as replaceable as her role in the textile factory. In the scene preceding Milda´s return home, which was eventually cut out from the film, her substitutability is even more evident. In it, Milda is persistently trying to win another girl who is, however, immune to seducing techniques used by urban womanisers and is able to shake the importunate young man off.[6]

Fulfilling the desires of a young person in socialist Czechoslovakia seems impossible, moreover if the person is a young woman. Just like the female comrade educator tells the girls in her moralizing appeal at the boarding school: “A girl´s honour isn´t an easy thing.” A girl has to deserve a good boy by her honourable behaviour. If the boy is not nice to her, it is her fault and she should be ashamed. The boy, on the other hand, doesn´t have to do anything. At the most to transfer the guilt on someone else if he is blamed (just like Milda does at the end of the film while defending himself before his father by saying that he hadn´t invited Andula to Prague). The scene, which offers to be interpreted as a political allegory, also reveals the self-sustaining mechanism of authoritative regimes. The girls, at the instigation of the comrade educator, vote on the proposal that they should think about themselves and mend their ways. All are in favour. No matter how obviously they rise above the situation (this scene is followed by another with Andula hitchhiking a car to take her to Prague), they still accept their role in the system.

We realize how important it is for a totalitarian system that its citizens keep checking each other while watching the last of the three spatiotemporally closed blocks that constitute the narration. Milda´s mother (Milada Ježková), interested in what hides in Andula´s suitcase, first asks her spouse (Josef Šebánek) to perform the girl´s luggage check. He, above all things, prefers silence and relaxing. His apathy illustrates the spiritual smallness of the indifferent and grown-lazy generation of fathers. That´s why the initiative mother subsequently assumes the task and, with the sound of the state anthem! playing in the background opens the suitcase and inspects its contents.

Andula´s preceding interrogation is the cause of similar, uncomfortable feelings, because it puts her in the position she shared with other girls before the female comrade. The parents’ generation understands the young just as little as the communist party. They don´t listen to them, neither they can hold a dialog with them. They only make commands or – just like Milda´s mother – ask questions they don´t expect to be answered. Even though it was Milda, who acted in a silly and irresponsible way by inviting Andula to his home without the knowledge of his parents (and without expecting that she might actually take him seriously), she is the one who should be ashamed because she “let him dupe her right away”.

At the end of the sequence, the girl, being the subject of a secondary victimization, finds herself out of the family discourse and also the camera´s focus. While we are having a great time watching the legendary bedroom scene with oppressed Milda and his mutually incompatible parents we tend to forget about Andula listening behind the door. When the camera finally returns to the kneeling and crying girl, we have to think again about whom and what we were actually laughing at and what kind of laughter it in fact was.

Loves of a Blonde shows the topic of intergenerational conflicts and the effort to get one´s individuality through regardless the forming pressure of their environment with a mix of irony and empathy. The captured moral climate, however, makes one shiver. Everyone refuses guilt and no one is able to take responsibility for their actions, let alone for the actions of others. People are mistrustful, controlled by the party and fear.

These social phenomena, which Forman´s second feature film illustrates with a series of casually staged situations (rather than by telling a continuous story or looking into the characters´ souls) most painfully falls on unhappy Andula. She, however, shows the biggest courage (and individuality) by confronting violent Tonda and by leaving the town which doesn´t offer many opportunities for spiritual or other growth but her act of resistance doesn´t have a lasting effect. On the contrary, we might start to speculate whether it won´t reinforce the same kind of resignation on a quality life, just as it is most faithfully represented by Milda´s father.

Martin Šrajer

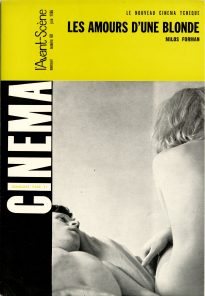

Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky, Czechoslovakia, 1965), director: Miloš Forman, screenplay: Jaroslav Papoušek, Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, director of photography: Miroslav Ondříček, music: Evžen Illín, editor: Miroslav Hájek, cast: Hana Brejchová, Vladimír Pucholt, Vladimír Menšík, Ivan Kheil, Jiří Hrubý, Milada Ježková, Josef Šebánek et al. Filmové studio Barrandov, 77 min.

Notes:

[1] Forman, Miloš, Novák, Jan, Co já vím? Brno: Atlantis 1994, p. 119.

[2] You can watch the films Konkurs and Kdyby ty muziky nebyly on a YouTube channel called Česká filmová klasika: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lavhN6cHLpw&t=1940s

[3] In the technical script, Tonda´s actions are explained by the need to earn money through selling the ring in order to pay for the abortion of a girl Tonda had cheated Andula with.

[4] Such as the incidental remark of her attempt to commit suicide during the conversation with Milda on the stairs.

[5] And it is exactly self-defence that Milda teaches Andula in one of the two cut-out scenes which precede the scene with Hana Brejchová´s naked back. It is a part of his plan to seduce the girl and bed her.

[6] The girl directs Milda towards the window of someone else´s flat. Similar to the struggle with the window blind, follows a situation which reminds us of silent slapstick comedies. The tenants consider Milda a thief and he attracts unwanted attention from two public security members (policemen), from whom he then starts to flight.