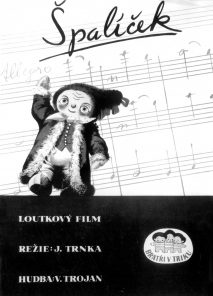

Jiří Trnka’s first feature puppet film, which won for instance the Gold Medal at the Venice IFF, was created by joining together six shorts originally filmed and screened separately. For the press in 1947, Czech Year represented an example of a mature work of art stemming from nationalness and folk traditions.

Trnka, a theatre stage and costume designer, painter, graphic artist, sculptor and illustrator, started his film career in 1942 as the costume designer of Miroslav Cikán’s unfinished fairy-tale Long, Broad and Sharpsight (Dlouhý, Široký a Bystrozraký). In 1945, he became the artistic director of the Bratři v Triku Studio (Formerly AFIT). Just a few weeks after the liberation of Czechoslovakia, on 15 June 1945, the studio began work on the first coloured animated fairy-tale based on a classic tale titled Grandpa Planted a Beet (Zasadil dědek řepu, 1945). It was followed by the short films The Gift (Dárek), Springman and the SS (Pérák a SS)and The Animals and the Brigands (all 1946).[1] In 1946, Trnka, along with Břetislav Pojar, Stanislav Látal and Václav Trojan, a composer of music for radio and operas for children, left Bratři v Triku and founded their Studio of Puppet Film (Studio loutkového filmu) under improvised conditions in the Chour Houses on Národní street in Prague.

The first of the six Czech Year segments was Bethlehem (Betlém). It was also Trnka’s first attempt to direct a puppet film.[2] At that time, constrained by the hectic filming schedule in the fall of 1946 (the film was supposed to be done by Christmas), Trnka didn’t yet consider making other parts of the film; it was supposed to be a test of a new graphic style and a new method of narration: “Until Czech Year, or until finishing Bethlehem, to be precise, I built my films exclusively around their artistic style. That determined their dramaturgy and the whole narration method. But the longer I spent working on the film, the less importance I saw in the artistic style, even though it was always me who still took care of it.”[3]

Realising the imperfections of the result, Trnka decided to accompany the 12-minute-long suite with another five episodes exploring folk customs and traditions kept in the Czech countryside during individual seasons. The framework was provided by Špalíček národních písní a říkadel (Book of National Songs and Rhymes), where Mikoláš Aleš offered illustrations to accompany national songs, seasonal lore and sayings. The tone was set in advance thanks to Trojan’s score, rooted in older and newer folk songs performed by the Kühn Children’s Choir. Let’s hear more about the genesis of the project from Václav Trojan himself: “In 1945, Jiří Trnka asked me to work on an animated film […] One year later, I was commissioned to work on Betlehem […] We used Christmas carols and their epic influenced the script. We were so immersed in our work that we, unfortunately, didn’t finish in time for Christmas. So we decided to make a whole year of national traditions […] and that’s how Czech Year was made.”[4]

A collective of 15 people including Trnka and producer Jílovec worked on the film for an entire year so that it would be ready for the following Christmas. The script, whose author was allegedly Trnka, was made according to individual bars of the score. The creation of puppets typologically inspired by folk art also proved to be quite a challenge. Trnka’s team first worked with puppets used in classical puppet theatre, but because of their fragile wire frames, they were breaking constantly. Therefore, the team decided to replace them with puppets with more durable metal frames and flexible metal joints that could stay in position for as long as necessary (each movement had to be filmed separately). The puppets’ faces are not movable, even though they have adequately dramatic expressions and eyes to make the film’s meanings comprehensible to the audiences. A more detailed analysis of the “performances” of Trnka’s puppets was offered by Marie Benešová: “The movement of the puppets includes basic dance figures which are, however, incorporated in the action on the screen; in style with realistic objects and background, their movement is transformed into a stylised gesture surprising with its smoothness, fluidity and expressiveness.”[5]

In 1980, Břetislav Pojar shed some light on the strenuous production process: “Bethlehem is a classic example of Trnka’s mastery: he was able to extract a strong emotional effect out of a static image and use it to portray the mental state of a puppet. It’s the scene with the one-legged veteran kneeling in front of the crib. It was shot with a long pan revolving around the Bethlehem hill all the way to a close-up of the kneeling soldier. In this respect, Trnka was a true master. He turned on a fan so that the puppet’s hair would move a little to create the impression that the figure wasn’t motionless. He concentrated everything else on the atmosphere, the expression of the puppet’s face, which he enhanced by lighting and the tiny detail of wind-blown hair. In connection with the music, he conjured up an impression of a person deeply affected by emotions.”[6]

Bethlehem, which was made first, is actually the last segment of the 75-minute-long film depicting a year in the Czech countryside as reflected in songs, customs, rites and festivities. The other segments are Shrovetide, Spring, Legend about St. Prokop, The Fair and The Feast.

In the surrealistic Shrovetide, we observe a whirl and twirl of masks and people looking forward to the coming of spring. The lyrical Spring shows shepherds climbing hilltops, animals frolicking in pastures and the beginning of the harvest. The mythological Legend about St. Prokop adapts a legend about a saint who repented for his sins in the forests near the Sázava River, accompanied by forest animals. The Fair depicts a procession to a chapel with a magical spring, while in the Brueghelesque The Feast, villagers enjoy a great banquet and Bethlehem, the closing segment of which some critics perceive as the weakest part of the whole, gives a vivid picture of a Czech Christmas in a carol about the birth of Christ.

On 17 December 1947, Czech Year received permission for public screening. Eight days later, symbolically on Christmas, the film had its premiere (it was screened with Trnka’s short film The Gift. In Filmové noviny, Bohumil Brejcha recommended a national perspective for viewing the script: “Czech Year needs to be received […] with an open heart and open mind; one must identify oneself with the fates of the film’s characters and explore the morale of these stories in order to find a piece of life’s truth embedded in them by centuries of Czech national traditions.”[7] Thanks to its “formal purity, technical perfection, stylistic and artistic innovativeness,” but also for its “nationalness,” Czech Year received the newly created award of Czech film journalists, who didn’t forget to note that the film first and foremost was a success of the nationalised Czechoslovak cinema.[8]

On Wednesday, 18 August 1948, the Venice IFF began. Trnka’s Czech Year won the festival’s Gold Medal for best puppet film. A testimony to the political perception of cinema was the fact that the Minister of Information published his congratulations in the press: “I would like to sincerely congratulate Czech Year for the immense success and the received award. I am pleased that you bring fame to the nationalised Czechoslovak cinema.”[9] The work of Trnka’s studio became a mark of quality and paved the way that Czech animation was to take in the following years, represented at foreign festivals by Trnka himself along with Břetislav Pojar, Hermína Týrlová and Karel Zeman. Also the participation of other renowned Czech artist from various fields played a significant role (Josef Lada, Kamil Lhoták, Zdeněk Seydl, E. F. Burian, Ilja Hurník, František Škvor, Jiří Brdečka…).[10]

In the 1960s, Trnka himself – also in the light of the international presentation of his work (the first segment of Czech Year was selected to be a part of a gift to Stalin for his birthday) – took a stance against using films to spread ideology and concepts (nationalness, Czech character) conforming to the ruling regime. “In puppet or animated film, you cannot just serve daily needs. You have the press for that. Our work is of long-term character, and the validity of the stories cannot vanish with time. Their message must be deeper.”[11] Let’s respect his point of view and use the opinions of experts to perceive Czech Year as an aesthetic object instead of ideologic.

Oldřich Kautský tried to describe the film’s effect on viewers: “Its rapid cuts and exclusive symbolism of some images requires not only imagination but also some eye fatigue. As a reward, it gives the viewers this undefined feeling of joy of a new experience and a perfect catharsis for adults who become children again for two hours.”[12] Marie Benešová used a specific segment of Czech Year to illustrate its qualities: “The puppet play about the Turk and Kateřinais Czech Year’s most beautiful sequence; it is superb in its emotionally compelling compressed story and masterful montage, but mainly in its message in which the plot permeates Trnka’s artistic expressions and his faith in magic and the suggestive power of art.”[13]

One of the most avid supporters of Trnka’s film was the multimedia artist Emil Radok, co-founder of Laterna magika: “The whole film, unimaginably charming, oscillates from the purest artistic expression to reality and beyond; however, the purpose of these shapeable devices leads to a majestic artistic realism. Only a few live action films have such a supreme script as Czech Year. Not one single image, not one single scene is pointless; not one single transition is flawed. The colour achieves such perfection that live action films cannot even dream of.” [14]

Martin Šrajer

Notes:

[1] The Animals and the Brigands won the Grand International Prize for the Best Animated Short in Cannes in 1946. This wasn’t the only big success of Czech animation before The Czech Year. At the 1947 Brussels IFF, puppet film Bethlehem and animated film Ready, Let’s Go (Hotovo, jedem, 1946) were awarded special mentions. At the 1947 Venice IFF, the International Prize for the Best Animated Film was awarded to Atom at a Crossroads (Atom na rozcestí, 1947) and the Prize for the Best Puppet Film to The Feast (Posvícení, 1947).

[2] The film was inspired by Trnka’s oil painting of the same name.

[3] Jaroslav Brož, Dvacet let čs. filmu. Vypovídá Jiří Trnka. Film a doba 11, 1965, no. 6, p. 290.

[4] Jaroslav Kovaříček, Hned několik důvodů k rozhovoru s Václavem Trojanem. Kino 22, 1967, no. 11 (1st June), p. 2

[5] Marie Benešová, Od Špalíčku ke Snu noci svatojanské. Praha: Orbis 1961, p. 11.

[6] Marie Benešová, Návraty. Zamyšlení nad migrací motivů v tvorbě Jiřího Trnky. Film a doba 33, 1987, no. 2, p. 79.

[7] Bohumil Brejcha, Špalíček. Filmové noviny 1, 1947, no. 51 (20th December), p. 3.

[8] Oldřich Kautský, Cena kritiků Špalíčku. Filmové noviny 2, 1948, no. 1, p. 1.

[9] Congratulations to puppet film. Filmové noviny 2, 1948, no. 2 (10th January), p. 1.

[10] Selling colour copies of puppet and animated films abroad was difficult because of the lack of colour material and preview copies.

[11] J. Brož, Jaroslav, c. d., p. 290.

[12] Oldřich Kautský, Čemu jsme dali věnec. Filmové noviny 2, 1948, no. 1, p. 7.

[13] M. Benešová, Návraty, p. 80.

[14] Emil Radok, Démant české kultury – světové dílo. Práce 1947, no. 297 (21st December), p. 6.