Once again, a certain film festival was held, and once again, directors were mentioned as the only filmmakers behind films. Even The Defendant was referred to as a film by Kadár-Klos, while…

I wouldn’t want to dedicate the first interview of my life solely to this issue. But it’s time to talk about it because it has grown to egregious proportions. I mean the status and situation of screenwriters in general. The directors are certainly not to blame, it’s the fault of the production system. Not even the structure of director remuneration for their dramaturgical and screenwriting cooperation is in order. Essentially, they’re supposed to define how the script should look like. This work is subsequently remunerated by a portion of the fee for screenwriting. And that’s where many misunderstandings occur. For instance, everyone would consider it absurd if the director demanded a fee for guiding the camera even though it is the director who determines the optics of the scene, the sharpness, position of the camera and the image tone. It would be equally absurd if the director was to get a part of the actors’ salary even though it’s the director who literally directs every movement of the actors. This, of course, cannot happen as during the time the director is in direct contact with other professions, i.e. during the shooting, his work is remunerated. That’s the usual and established convention. I don’t want to destroy it, as my words could suggest, I just find it important to point out these discrepancies most urgently in order to prevent the consequences stemming from this practice.

What consequences do you mean?

The morally-artistical profit at the end of the film; if it’s good. The public and mainly the press transfer the merit to the directors and that leads to embarrassing and even absurd situations, as I witnessed many times. If the film is bad, the reviewers usually don’t forget to mention the poor screenwriters without even reading what they wrote. That’s why I think the worst of it all is when the literary authors are actually freed from socio-moral responsibility. If screenwriters are ignored, they can write only for profit without caring about how the film is going to turn out. The film will not be theirs anyway. In the coming era of Czechoslovak and world cinema, this means a dangerous delay.

That’s one aspect of the problem. These conclusions are valid for the part of filmmaking with ambitions and artistic losses caused by professional shortcomings and wrong interpretations of the script which may bring forth a questionable reception of the film. But there aren’t many cases when a good script is ruined by bad directing. The consequences of this system are much worse for average screenwriters who prefer to choose a certain kind of uniformity guaranteeing smooth production and low-key premieres.

The danger of uniformity is certainly present. But it’s, of course, different with scripts written by renowned authors. They get more respect but I think that ultimately their films end up the same way. The situation is much more shameless with scripts not written by distinctive writers.

For instance those who adapt somebody else’s work? What’s the most shameless thing about that?

The negation of the morally artistic contribution to the film, the compression of merit only to one director or another.

And isn’t the “anonymity” of screenwriters caused mainly by the fact that not every screenwriter comes with an original theme and concept that would captivate and intrigue the public, forcing it to remember their name?

I don’t wish to speak for screenwriters, there are other people who can summarize that. I just found the same acerbating feelings that I have in my colleagues.

I think that not even the question of the “processors” isn’t simple. For instance Fellini’s collaborators are excellent screenwriters. And yet, after seeing a film by Fellini, we would hardly place their names on the same level as his. The value of his films is in the way in which the literary text of the script was brought to life. After all, no script, not even the most perfect one, cannot hold such validity as a completed film as it doesn’t include the imagery dynamics, its value can be estimated only by the extent to which it fulfils the requirement of being ready to be brought on screen, that’s its purpose. And if it can excel only in the form of a completed film – its final form – the director’s merit is important. The most important thing is the subject of the script itself, its concept, the original impulse which may come from the screenwriter as well as the director. Unfortunately, to screenwriters’ disadvantage, the inspirers behind most great films – evidence can be found in the history of cinema – were directors who knew exactly what they wanted from the script even before it was written. And the situation hasn’t changed. This applies not only to Fellini, but other directors such as Antonioni, Bergman, Resnais, Welles, Tarkovsky and many more.

Sure. But we also know the movement founded and led by Zavattini. It made a huge impression on me because it was an expression of a certain socially artistic movement. It spawned a series of films made by various directors. It was an expression of creative maturity of Italian cinema in a certain period of its development preceded by a period of searching, which we are witnessing here now. Today, after a certain renaissance of film professions, especially directing, the time has come for those who will have to do the same in screenwriting. I don’t want to deny the contribution of Chytilová and Forman because they break conventions which, as the time passed, clung to filmmaking, by searching for their own style. But their films give away a certain lack of screenwriting concept. As a result, their films aren’t rich in thought-provoking themes. That is yet to come. I think even Jasný’s The Cassandra Cat in some way represents the search for form. I think we’re still waiting for a well-founded dramaturgy, an erudite work with a pen which can give these original manuscripts a thought concept in addition to their professional concept. Sure, they can do it themselves. And that’s my point. Right now it’s negated, ignored. That’s why I say again that ignoring the work of screenwriters won’t get us any closer to this goal. What we’re missing is a parallel development of screenwriting. And that’s regrettable. I think that screenwriting can contribute to development to a much bigger extent than it does now. It seems to me that our film industry is split into a group of “professional” conventional films and a group of elite experimenting directors who achieve only partial success without good scripts.

If I understand this correctly, you want a generation of screenwriters, or rather authors such as Kapler and Gabrilovitch in Soviet cinema and Prévert and Spaak, and lately Duras, in French cinema, who managed to give a new direction and concept to world cinematography thereby predetermining future quality standards?

Yes, I’m talking about a similar situation. You can see that my estimate in this direction is probably right. I have no idea who the most important screenwriter will be and who will establish such movement or group. So far, we can only talk about such person and wait for someone to come with a big script on a silver platter. But even with this kind of script, it won’t be easy. There are situations when a screenwriter’s only chance to get moral satisfaction is to apply for the director’s seat as well so that they have a guarantee their intentions won’t be twisted. But it would be more meritorious if they stuck to screenwriting. If such writers leave dramaturgy, it’s unhealthy.

So you would be satisfied with directors such as Kramer, who provide a guarantee of an intelligent “interpretation” of the script, perfect directing, but are sometimes a bit impersonal in professional perfection; directors able to stay behind the scenes and avoid affecting the film with the heat of their temperament, put out the sparkles of immediate improvisation and not imprint their exclusive distinctiveness upon the film?

Thy should be responsible for 70 to 80 % of film production in every industry, because there aren’t many directors-screenwriters. The rest, presented as such, are only megalomaniac attempts.

I agree with you. But directors-screenwriters have always been huge triumphs of cinema and their films its milestones.

When I think about films made in 1963-64, I cannot recall more than two or three authorial films. All the other films have a fleeting value, they will be forgotten. Because they didn’t have screenwriters. I have a very good relationship with Vojtěch Jasný, whom I’ve known for many years. He’s a director who can be a screenwriter, but he can also direct someone else’s script with an honest dose of professionality and it’s always a creative act.

But he was always best with “his” themes – Desire, The Cassandra Cat.

But he cannot keep doing that every year. I wrote Desire together with him. I witnessed his most intensive creative process while working on it. I say that no director can keep doing that every year. They have to rest and search and explore topics for their new films. For a director-screenwriter, each film represents a certain period of life. Jasný, therefore, manages to make an “ordinary” film between “his” films. I’m currently working on a script for him. He is interested in the script but his relation to it is not so “authorial” as it is with The Cassandra Cat. But he has his own authorial film, The Chimneysweep which he has postponed, letting the theme mature. It’s always a longer process, it needs its time. I can also closely observe Vláčil’s work. He’s got a similar process. He definitely cannot release an authorial film every year. That’s beyond human capabilities. That’s an entirely different category of film production I’m not mentioning in relation to the script issues. Such films will always be in the limelight, and deservedly so.

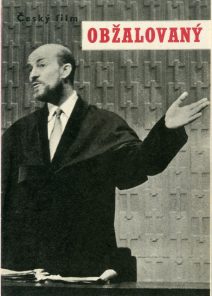

Let’s get back to The Defendant and to the reason it was labelled an authorial film. The critics might have been familiar with Hašková’s story, from which the film differs in many points; they know the previous work of the duo and therefore so enthusiastically praise new elements in their direction. But the original process of the very birth of the film, the screenwriting process which crystallised the concept of The Defendant, remained unknown to them. Could you illuminate this important phase of production?

I had to fight very hard for The Defendant’s concept. It was against conventions and some shortcomings of the script were caused by the fact that I had to add some things, such as the journalists, in order to make it – in a nutshell – clear what was happening in the proceedings. This is naturally a fault of the whole concept, an expression of distrust to this kind of engaged film. You can find proof in the technical script which changed the entire concept of my literary script. I’m not saying that the director has no right to make changes. You see, films are made in studios and it’s a matter of the screenwriter’s honour to make sure that his work on the film doesn’t end with script approval. If the director is interested, the screenwriter should be present in the studio and contribute to the final shape of the film. Everything in the production process – actors, camera – should be aligned with the script and the script should be aligned with it. With The Defendant, everything happened on the go because Kadár and Klos approached the concept differently. I appreciate the tolerance they have while considering other opinions which they are in the end capable of accepting, provided that they’re good. The concept of the film isn’t always exclusively determined by the director. With our The Defendant, it was important that there was an opening to make and engaged film. The term itself was discredited in the past because films of this type used to be deceitful. The biggest victory and pleasure from the awards The Defendant won, was that the film proved that it is possible to go this way. On this occasion, I would like to mention the story Angel from Desire – it was the same case as Accused. Perhaps even more. I say it because every new script of this type will meet a lesser trust in its how it will turn out. Because until the moment Kadár and Klos backed the script after the first discussion of the artistic council, there wasn’t much belief in the film’s artistic outcome. Its dialogue shape and its seemingly low attractiveness didn’t bring much hope. I was afraid that I was writing the script only to put it in the drawer.

So what made you continue?

There is a certain moral and thought inspiration. I still felt convinced that the closer I get to the truth and the more courage I will have to tell it, the more it will guarantee the film’s success. Far more important than the script’s overall shape was to create the film’s hero. In this regard, I appreciate its success the most. I’d say that our hero is a tragic type of the present. It’s a person who serves social development, a person who is the salt of the earth and gets no gratitude for his work.

Is he really tragic?

I think he is. I see the tragedy in that it’s not an exclusive and only case. There are many people like that. They are torn in a conflict between sense and dogma, sense and hypocrisy, honour and lies or cowardice.

Did you think about using this theme in a literary work?

I prefer working for film and television. It offers a maximum potential for my work and I get satisfaction, pleasure and ambition. I could put the immortality and the dynamics of an individual film’s message in direct opposition. The fact that a socially engaged film makes an impression on millions of viewers within one or several seasons means that it spreads its message. This naturally means that such work is drained much more quickly than a book as the message of a book, whose effect is much slower and less potent and collective than a message conveyed by film and television.

Do you consider this type of engaged films as the most significant expression of modern film art?

I definitely feel that socially engaged films has a future. As long as society has thorny problems, there is a future for this kind of films.

As the trends in world cinematography suggest, socially engaged films stopped being exclusive for socialist cinemas. Such films, and good ones, I must add, are now made all over the world, even though their focus is diverse and they don’t always serve a good purpose.

The danger for this kind of films arises when they get in tow of a political machinery. If artists willingly or unwillingly start to serve falsely treated social orders. After all, we experienced that in the previous decade and it drove audiences away from the cinemas.

What is your opinion on the American “engaged” film The Best Man?

I didn’t find it satisfying. I saw better American films of this kind. For instance Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Twelve Angry Men, which served as a certain morally legal inspiration for The Defendant, made a much bigger impression on me. The Best Man lacks something. I think the author didn’t manage to put a sufficiently formidable force and personality against the negative type. Naturally I don’t know how truthful my assessment is. I cannot give a decisive assessment. I haven’t been to the US.

And what do you think about Kazan’s America America?

Kazan said he made the film for Americans in order to remind them of their immigrant origins. I would say democratic. But I see something more universal in this film. When looking at the film, I deduce a passionate declaration of human right to choose the place and country to live. People like Stavros exist to this day. They are certainly not heroes, they’re perhaps just selfish, their desire to leave transforms into passion to which they’re willing to sacrifice morale, but I don’t see any right a society can have to put obstacles into the way of such people. And it’s in the reflection of these issues where I still see the film’s engagement.

What do you think is the biggest benefit of engaged films?

Unlike literary documentary testimonies and non-fiction literature, they don’t dwell on capturing the outer shape of the world, they are serious contemplations on important questions, on the meaning of life. It means that they are or are supposed be tantamount to any work of art. They don’t strive for aesthetic perfection, but they want to exceed the boundaries of the viewers’ artistic experience. They aim to affect their lives. And if they succeed and get a response, that’s the benefit.

For the moment… But a part of artistic ambition is the longevity of the work. Will our engaged films still be valid in the future?

I’m afraid that those who “knowingly” create something for a bright future, tend to be forgotten. I have seen enough human sorrows and pain, but also pettiness caused by all those events recorded in capital letters. I haven’t thought about immortality, but I believe that works of art honestly trying to liberate their generation from such conflicts, will inspire response even later on. Because only the truth can survive, not an illusion. And that’s the answer to the question of engaged film’s place and importance in history. Making films for people is something more than just a ticklish comforter on the silver screen, something more than a mere shadow illusion.

Galina Kopaněvová

Film a doba 10, 1964, no. 10, pp. 508–511.