When talking about films such as The Bagpipes Play (Hrály dudy, 1953), On a Green Field (Na zelené louce, 1955), Children’s Spring (Dětské jaro, 1956), Rosana (1956), Piana Ligna (1961) and Concerto Glassico (1962), only a few film historians and enthusiasts remember the name of their director Ladislav Rychman. When considering the whole extensive filmography of this filmmaker, the abovementioned films represent but a mere fraction. However, we shouldn’t perceive them as marginal and insignificant production because without the experience gained making them, Rychman’s best-known work – first Czechoslovak musical The Hop-Pickers (Starci na chmelu, 1964) – would only hardly resonate in our cultural memory. Through work on the aforementioned folklore films and advertising formats, later also on television songs, Rychman not only gained filmmaking experience, but mainly established and refined his creative trademark connected to his life-long passion for music and subsequent interest to innovatively combine audio and video elements of films. As a result, it became characteristic of his work.

Artistic career of Ladislav Rychman encompasses theatre, polyecran projects, advertising formats, short and feature films, various genres from detective stories to sci-fi horror comedies, but his domain were musical films and musicals. But the list of Rychman’s work cannot be reduced only to cinema. An inseparable and significant part of his diverse multi-media career trajectory is formed by formats designed for television screens: television songs as predecessors of today’s music videos, musical revue and a wide range of entertainment programmes, short stories and edited archive footage. In his work, Rychman didn’t focus only on direction, he also actively searched for topics to adapt, wrote scripts, significantly contributed to musical dramaturgy, deliberated over the technical concepts of his films and, using his experience from advertising, planned promotional campaigns for his projects.

By combining all elements of artistic expression, i.e. music, spoken word, dancing and singing, Rychman became a synthetic artist. His ability to transfer between cultural industries, several media and various formats as an inter- and multimedia creator, secured him a unique position in our audiovisual culture; only few other filmmakers were able to keep such profile continually and over a long career – in case of Rychman spanning over five decades.

Ladislav Rychman is also an example of a genre filmmaker primarily, purposefully and systematically pursuing popular entertainment. This field may be attractive for audiences, but from the perspective of socially critical reception, based on the historical opposition against “high art,” it’s rather debatable. This was evidenced by a mixed reception of his work after The Hop-Pickers which was used as a benchmark for anything that came after it. That’s why Rychman considered himself to be “a man cursed by The Hop-Pickers.”[1] But Rychman always placed the audience first and – due to his own traumatic experiences from the war – wanted to give them a relaxing escape from reality linked to a spectacle or an impression of something unique. But he always appealed to their morale and included a motif for contemplation. And it was entertaining genres, mainly with music and dancing, that enabled him to do just that.

Before for The Hop-Pickers

As far as Rychman’s feature films are concerned, his film musicals were preceded by two genre films based on scripts assigned to Rychman by the Barrandov Film Studio which approached him in 1956. In 1957, he debuted with The Case is Not Yet Closed (Případ ještě nekončí), a detective story about an investigation of a theft of an anti-Tetanus serum patent from the National Institute of Experimental Medicine. Two years later, he directed an intimate psychological drama The Circle (Kruh) about a mother of three who tries to come to terms with her husband’s infidelity and in the process finds a path to emancipation. Rychman couldn’t influence the selection of the scripts, but he saw it as an opportunity to move from short films to feature live-action films which he wanted to do. In retrospect, he viewed the authorship of these films rather detrimentally as it diverted him from the preferred musical path.

On his way to the first musical, he also had to overcome the reserved attitude of Barrandov to this genre, as it didn’t fit the ideological criteria of the late 1950s and early 1960s. During that time, however, Rychman worked in Czechoslovak Television where the rules for entertainment programmes were not so strict so he could use his invention there. In 1958, he made a New Year’s special titled A Night with no Flaws (Dnes večer bez závady) according to the script by Vratislav Blažek and included a film/television version of a song titled Dáme si do bytu. He later said that this idea was more or less a coincidence as he needed to fill some time and decided to film a song, but due to his professional orientation and artistic background, Dáme si do bytu seems to be a logical conclusion and materialisation of his creative visions. He filmed several more songs for television such as Mackie Messer, Obnošená vesta, Dominiku, Chtěl bych mít kapelu and more.

This inconspicuous short format gave ground for a phenomenon popular among the audiences. It not only gradually became a stable part of the programme and bigger programme blocks, but it inspired collaboration between cultural industries and helped to establish the cult of popstars.[2] In addition, television songs achieved international success in the 1960s and became a sought-after export article.[3] In 1961, Czechoslovak Television management approached Rychman with an offer to make an entertainment programme that would represent Czechoslovak Television at the first International Festival in Entertainment Broadcasting in Montreaux, Switzerland. Pressed for time, Rychman chose several completed songs by various directors from the archive and filmed connecting scenes adding a narrative cohesion to otherwise disparate pieces. His revue Thousand Looks Behind the Scenes (Tisíc pohledů za kulisy) won the Bronze Rose and opened further possibilities for popular music to storm the television screens. In this revue, Rychman also explored the dramaturgy of bigger musical programmes. He utilised all experiences in The Hop-Pickers and other film musicals.

Musical Triptych

The basic principle of a musical is an organic blending of music, dance, singing and spoken word into a synthetic shape in which all elements push forward the narrative. From Rychman’s filmography, the following three films are in accordance with the abovementioned principle: The Hop-Pickers (Starci na chmelu, 1964), The Lady of the Lines (Dáma na kolejích, 1966) and A Star is Falling Upwards (Hvězda padá vzhůru, 1974). Rychman later described these films as a musical triptych. The Hop-Pickers, exploring the theme of generational and moral confrontation, used modern songs and many known and unknown actors to attract young people to the cinemas. Rychman conceived The Lady in the style of a popular light opera, the script was written for popular actress Jiřina Bohdalová and with the plot revolving around marriage and female emancipation, the film was intended for a more mature audience. Star was an adaptation of Josef Kajetán Tyl’s stage play Strakonický dudák and was supposed to be centred around a popular singer.

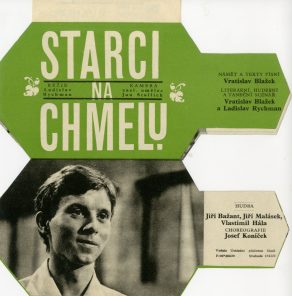

The first two films, often reprised to this day, stand out from the triptych as well as Rychman’s filmography mainly for two reasons. They were both written by Vratislav Blažek whose scripts were unique in that they smoothly transferred from spoken word to song which were subsequently and naturally linked to dialogues and helped to drive the narrative, thus creating a coherent work. The second is reason is the score selected by an “audition method.” All three composers – Jiří Malásek, Jiří Bažant and Vlastimil Hála – composed music for individual songs independently and then, on a meeting with Rychman and Blažek, they chose the most suitable music for the scene together. Rychman had the decisive vote as he not only saw specific scenes in his head, but he also heard them as well. Jiří Malásek, his long-time friend and collaborator, said: “Collaboration with Rychman is truly unparalleled. He is a musician and he knows exactly what he wants from people.”[4] Their collaboration bore fruits in the form of hits which subsequently cemented their place in our popular music and culture.

The tried and tested team of Blažek, Rychman, Malásek, Bažant and Hála worked on a modern musical paraphrase of Scheherazade. But in light of the changes in social and political climate after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the project was shelved. Not long after that, Vratislav Blažek emigrated and Rychman found himself without a unique musical screenwriter he wasn’t able to replace. Unlike The Hop-Pickers and The Lady, the third musical A Star is Falling Upwards was created by a different creative group in different production conditions. When The Lady of the Lines was released, Rychman announced: “I would like to make one more big musical, a true show with Matuška, Gott, Neckář, Hegerová and genuinely catchy melodies.” In 1967, he filmed several television songs with the signers from the Apollo theatre whose founders and managers were Jiří and Ladislav Štaidl and main star Karel Gott. Together, they created A Star is Falling Upwards released in 1974. The origins of this project date back to the years 1967–1968. In December, Ladislav Štaidl wrote a film story Comets and Admirers (Komety a ctitelé). It is evident that the story was written as a star vehicle for Karel Gott. What’s also evident is the influence of the normalisation ideology on the final version of the film. Due to various production, social and political circumstances and because the creators and actors had other engagements, the film was made in 1973–1974. Although benefiting from a skilled directorial approach and style, the film has a bad script and long running length. Karel Gott was able to utilise his voice and star power, but his acting performance was sub-par. In addition, the Štaidl brothers, authors of many hits, didn’t manage to write attractive songs that would become hits and draw attention to the film. But despite the fact that critics and some historians condemn and ridicule this project and viewers prefer Rychman’s previous musicals, it remains interesting for research purposes.

Creative Approach and Aesthetics

Although the films of the triptych differ in some aspects, they share characteristic methods and attributes of Rychman’s style identifiable not only in his feature films and musicals. It is also apparent that Rychman made an effort to vary them.

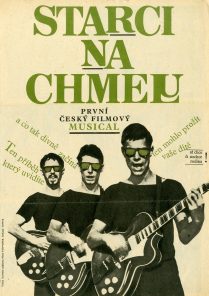

In terms of narration, Rychman typically comments the plot with a “choir.” Regarding the inspiration for the three guitarists in The Hop-Pickers, he said: “I believe in fate. And in Greek tragedies, fate is always somehow present. There is also a choir providing commentary. So I thought I would replace the ancient Greek choir with three anonymous guitarists who would provide narration and commentary.”[5] In The Hop-Pickers, these characters are not directly involved, but they appear in separate scenes in suitable moments and play their songs. Dressed in black, guitars over their shoulders and with sunglasses, they symbolise the rock’n’roll fever of the 1960s. Thanks to their image, the guitarists were so attractive that they were included in the promotional campaign, appeared on posters, on the book cover, and a folding picture-book with the score for the film’s theme song Milenci v texaskách was shaped as a guitar. In The Lady of the Lines, the role of the choir is assigned to various groups of characters: plasterers, passenger of the tram driven by the film’s protagonist Marie, voices of female neighbours, bank clients, drivers taking their cars for a weekend drive. In A Star is Falling Upwards, there are three Fates. They endow the protagonist with talent, prophesy his destiny and help him fulfil it. In this case, the mysterious women are also included in the narrative and the plot. They don’t appear so often, but they do appear as various types of female characters in various costumes – for instance when Švanda needs to be persuaded to keep his lucky suit and when he needs a push to make his first public performance which launches his career.

Rychman used his traditional method also in his television work. For instance in 1975, he recycled the successful guitarists from The Hop-Pickers in a television film titled Summer Romance (Letní romance) or “an almost criminal ballad” starring Helena Vondráčková and Lubomír Lipský. Three men in flares typical for 1970s fashion appear at the very beginning when they hang the opening credits on wooden poles and recite poems from Erben’s Kytice. They reappear several times throughout the film, using modified poems by Erben and creating visual compositions with the protagonists who ignore them as the guitarists should remain anonymous and invisible to them.

Rychman used a different variation of the choir in Six Black-Haired Girls (Šest černých dívek anebo Proč zmizel zajíc?) from 1969. In this otherwise non-musical detective comedy based on Josef Škvorecký’s story A Crime in the Manuscript Library (Zločin v knihovně rukopisů), the role of the choir is assigned to non-diegetic female singing voices who at first foreshadow the detective plot: “The Book of Psalms went missing, missing, missing,” and “Professor Zajíc went missing, missing, missing” and later humorously lament the events: “Christ, what a mess,” “It can’t be, it can’t be,” “What a time, there’s no morals, what a time.” The choreography of the six girls’ movement and creating composition of these characters dressed in black imbue this purely detective film with light erotic tone with gracefulness and dance-like elements, thus alluding to similar stage set-up in Rychman’s television songs as well as The Hop-Pickers and Lady.

With his trademark style, Rychman also approached the adaptation of another text by Škvorecký, a film story titled How a Woman Bathes (Jak se koupe žena), one of three stories about Lieutenant Borůvka released in an anthology film titled The Crime at the Girls’ School (Zločin v dívčí škole, 1965). Rychman expanded the original titled Scientific Method with passages including music and dancing which are not self-serving or a mere creative lavishness. The rhythmical and lively opening scene with western elements takes place on the stage of a night club where a rehearsal of the evening’s show is underway. Rychman pulls the viewers directly into the film in which one of the dancers is murdered, acquaints them with some motifs and characters and outlines their personality traits so important for the subsequent investigation.

As an artist oscillating between music, film, television and theatre, Rychman transferred his gradually acquired creative know-how between various formats. In addition to his experience with filming television songs, the aesthetics of his musicals benefited also from his work on folklore and ethnographic films from the 1950s. In 1952, during the Festival of Folk Songs and Dance in Strážnice, he filmed various dances from various corners of Czechoslovakia. The result was a series of black-and-white instructional dancing videos aiming to create an audio-visual archive of disappearing cultural heritage. Rychman captured several dance partners and groups and gradually moved to increasingly detailed footage of individual steps and sequences. While making coloured suits On a Green Field (Na zelené loouce, 1955) and Children’s Spring (Dětské jaro, 1956), Rychman had more artistic freedom so the films look much more poetic. Rychman uses wide shots to emphasise the landscapes and villages in which he places children playing or young people singing and dancing. In dancing scenes, he often films the dancers from below and combines the footage with detailed footage of feet while dancing. He composes the image in several plans and switches focus – for instance looking through parts of dancing bodies to whole figures in the second or third plans. His work with complex scenes and mass dancing scenes, just like framing the detail through various opening is typical for the aesthetics of The Hop-Pickers.

Genre Modifications

Ladislav Rychman almost defied the stereotypical genre labels and expectations and “suffered” from a restless creative tension, wanting to cultivate the genre and make every new project special. He had the same plans for his project titled Lovers from a Kiosk (Milenci z kiosku) which eventually remained shelved. The script, based on a theatre play by Vítězslav Nezval and adapted by Rychman and Václav Nývlt in 1969, suggested that some dialogues were spoken and were meant to be sung, often changing in the middle of a sentence. In addition to the original characters, the authors added two extra characters who were supposed take on the role of an opera choir and even change costumes in in front of the cameras.

The effort to introduce constant innovation and formal changes to musical eventually proved counterproductive. Rychman didn’t want to promote his musical film Love at Second Sight (Láska na druhý pohled, 1981) as a musical at all and described it as a rhyme film with epigrammatic structure or a film with a musical commentary. But even socialist cinemas needed to attract viewers and the connection of Rychman plus musical did the trick. But labelling Love at Second Sight as a musical wasn’t the only reason behind unfavourable reviews. But although Rychman once again worked with fresh young faces (main roles were portrayed by Ilona Svobodová and Jan Čenský) and a more or less stable crew, wasn’t afraid to use modern technique and for dynamic and showy portrayal of mass dancing scene in a student use a Steadicam, the film lacked freshness and authenticity.

Although Rychman was often described as young in spirit, we can assume that in case of Love at Second Sight, a certain generation gap played its role because the authors were already in their sixties. Important is also the fact that the script had been in preparation for quite some time and wasn’t originally intended as a musical which meant the songs were added later. And Rychman himself rarely talked about this film in retrospect.

In 1982, Rychman got an offer from the Bratislava Koliba: “I should direct and original Slovak musical titled Cyrano from the Suburbs (script written by Alta Vášová) with music by Pavol Hammel and Marian Varga which promises and interesting work in itself.” [6] But the film version of this otherwise very successful theatre musical was never made. The last feature film Rychman made is a multi-genre version of a comedy with elements of sci-fi and horror Grandmothers Get Boosted (Babičky dobíjejte přesně, 1983). Due to health reasons, he subsequently focused on work for television and made many short films with popular actors. After 1989, as a life-long television fan, he began writing reviews for television programmes for magazine Svobodně slovo. From his long and varied career, Rychman himself paradoxically most appreciated an acclaimed and succesful project which is not very known in the Czech Republic – Noricam, a co-production polyecran made with scenographer Josef Svoboda and others in the 1970s for the city of Nurenberg to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the birth of German painter Albrecht Dürer.

Miroslava Papežová

Notes:

[1] Helena Hejčová, S Ladislavem Rychmanem: O jednom vzácném koření, Kino 37, 1982, no. 20, p. 5.

[2] Miroslava Papežová, Marta Kubišová: ne-herečka s cenou Thálie. České pop-hvězdy 60. let mezi divadlem, filmem a televizí, Iluminace 30, 2018, no. 2, pp. 77–92.

[3] Miroslava Papežová, Kdo, s kým, o čem, pro koho: Geneze formátu televizní písničky a spolupráce kulturních průmyslů v 60. letech v Československu, Iluminace 32, 2020, no. 2, pp. 5–29.

[4] Karol Sidon (ed.), Starci a klarinety. Prague: Orbis 1965, pp. 119–120.

[5] Andrej Halada, Filmový muzikál dnes neletí. Interview with Ladislav Rychman, Kinorevue, 6th November 1992, 23/92, p. 28.

[6] Helena Hejčová, op. cit., p. 5.