The Film Archive of the Army in Exile

The outbreak of World War II introduced an entirely new and unprecedented chapter in the history of cinema. Given the number of propaganda films that were made at this time, we can say without exaggeration that film also went to the war front. Whereas during World War I, world rulers were discovering the potential of the print press as a tool of propaganda, during World War II thein attention was focused on cinema. Film inevitably became an important tool for shaping public opinion – it was intended to prepare citizens for war, motivate them to action, and maintain social morale, among other things.

Some of the best-known films depicting Allied operations include the American cycle Why We Fight (Frank Capra, Anatole Litvak, 1942–1945), which covers the most important events of World War II; the British-American co-production The True Glory (Carol Reed, Garson Kanin, 1945), which documents the Allied victory on the Western Front; and Berlin (Fall of Berlin – 1945; Yuli Raizman, 1945), which follows the advance of Soviet troops from the onslaught at Stalingrad to the conquering of Berlin. These films contributed to the mythologisation of the great Allies, whose struggle against the Axis powers was not only a defence of their own statehood, but also a struggle to liberate weaker nations from Hitler’s oppression.

Lingering in the shadows of the films dealing with the war operations of the main Allied powers are others that describe the activities of smaller Allies, such as Australia, South Africa, Poland, and the Netherlands, as well as the Czechoslovak resistance. The motivating idea for those who created such productions was aptly described by director Jiří Weiss: “The average Brit is presented with Allied propaganda on a daily basis. Yet how does he perceive the content of those words, or thein importance? […] We should also show him the face of Poland, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia… The nations of the British isle and its Dominions as well as the United States would invest greater effort in industrial production and elsewhere if they saw real stories of the many different nations, which have laid aside their recent quarrels and now stand side by side. Have you seen how the British are redoubling their efforts to supply materials for the needs of our Soviet ally?”[1]

Although this call was only partially heeded, many film crews from individual countries, working in coordination with their respective governments-in-exile and the army, sought to capture on film the fight against the enemy. Films about the war in occupied nations were made primarily with the help of the British studio called the Crown Film Unit and the British Ministry of Information (MOI), however filmmakers with the Kuybyshev Newsreel Studio in the USSR and directors associated with the United States Office of War Information (OWI) and the Canadian National Film Board (NFB) also contributed to the creation of these films.[2]

Many of the productions made during World War II are now publicly available, but there are still other materials in film and military archives that are worth publishing – including footage that depicts the operations of peripheral Allied forces through their own lens. The collection We Will Remain Faithful contains just such material: films that document the Czechoslovak army operating on various fronts of the Second World War. While there are other films from the period that present this topic from the perspective of various Allied nations,[3] this edition focuses on the hitherto marginalised material shot by Czech filmmakers. Like the films of the other Allies, these works also responded to the film propaganda of the Axis states. Yet, as Jiří Weiss stressed, these films place simple soldiers at the centre of the action, and thus, together with other works of the Crown Film Unit, also provided a counterweight to the productions of the film establishment in Hollywood, Billancourt, or Barrandov.[4]

It should be noted that these films only present a narrow portion of the soldiers’ lives, which was, moreover (with the exception of some amateur film footage), extensively staged and “modified” for propagandistic purposes. Therefore, the goal of this edition is not only to present important factual information from Czech history, but also to initiate a consideration about the process of national mythologisation. The films provide examples of how Czechoslovak soldiers were perceived within the context of the worldwide armed conflict. They are a testament to the time of their origin and a sort of historical monument; they immortalise the contributions of Czechoslovak elites operating in the international arena and illustrate the nation’s struggle for freedom.

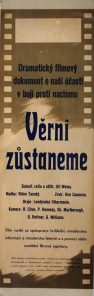

This edition is structured around the feature documentary Věrni zůstaneme (We Will Remain Faithful) – the first film to summarize the history of Czechoslovakia from the 1938 Munich Conference to the 1944 Allied landings in Normandy, France, with an emphasis on the resistance movement abroad. In addition to the sheer scale of this project, it is also important to note just how much weight was attached to the film’s mission. Years later, director Weiss recalled: “That immense faith, the vision of the future… (…) The crazy hope that film can affect people’s lives, can help change the world. It was the ideal of my generation to draw one’s heart like a sword and use art to fight for one’s convictions”.[5] The filmmaker was so convinced of the power of the documentary’s message that he allegedly organized an airdrop of copies of the film during the Allied deployment in support of the Slovak National Uprising.[6] The official premiere took place on October 12, 1945 in the Blaník cinema in Prague with the President of the newly restored Czechoslovak Republic in attendance. Several period reviews highlight the educational and patriotic value of the work. The journal Filmový přehled (Film Overview) described the documentary as a “living political textbook”, but also commented that it contains too little information about the units of General Ludvík Svoboda in the USSR, presumably due to the unavailability of such material.[7]

Of course, the complexity of the issues surrounding the operations of Czechoslovak units-in-exile demanded that the topic be presented from the broadest possible perspective. Czechoslovak soldiers were not only active on different fronts, on the ground and in the air, but were also subordinated to different political factions. It must be remembered that the discourse about the war had many modes of expression and went through various stages of development; it was nearly just as syncretic and extensive as the war itself. For this reason, the collection represents a diverse range of genres – documentary films, feature propaganda documentaries, newsreels, and amateur films – as well as raw footage from various fronts.

One group of works contains films made on various front-lines of battle (including the Western and Eastern Fronts, as well as fighting in Africa). The research for this project revealed that the collection of the Czech Národní filmový archiv (National Film Archive – NFA) are primarily dominated by materials about the operations of Czechoslovak troops on the Western Front. One of the reasons for this is the aforementioned Jiří Weiss, who was the most active Czech exile filmmaker during the war and later donated a collection of his films to the NFA. In addition to the documentary that lends its name to this collection, the extras include other film material shot by Weiss: the newsreel footage for Čechoslováci u Dunkerku, březen 1945 (Czechoslovaks at Dunkirk, March 1945) and Generál Liška hovoří o významu Dunkerku pro Československo 9. dubna 1945 (General Liška Speaks About the Significance of Dunkirk for Czechoslovakia on April 9, 1945) as well as the short documentary about the 311th Czechoslovak Squadron Night and Day (1945). From a film-historical point of view, the film The Czechoslovaks March On (1943), directed by Karel Lamač, also provides a remarkable portrait of Czechoslovak soldiers on the Western Front. This documentary stands out among the standard film propaganda of the time due to director’s subtle use of irony and the distance he maintains from his subject. It is worth noting that this film (like the documentary Night and Day) was produced by the Czechoslovak Film Unit. Although no detailed information has yet been found to this effect, it can be assumed that the film was created thanks to the financial support of then Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk.[8]

The situation of Czechoslovak airmen in England is also captured in the film material of 310. stíhací peruť (310th Fighter Squadron, 1940–1943) – one of the few examples of amateur footage in colour from the period, shot by military doctor Zdeněk Vítek on Eastman Kodak stock. The authentic atmosphere of the recorded moments is enhanced by the cameraman’s personal affiliation with the airmen and ground staff, who are filmed as they carry out their daily duties, engage in lemure activities, and participate in ceremonies and visits by representatives of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile (e.g. Jan Masaryk). The amateur footage consists of essentially continuous shots of individual events, which have barely been modified by subsequent editing and which are not even arranged chronologically in the preserved print. Given this lack of structure in the archived footage, the editors of this collection have decided to present this material in two edited fragments that illustrate as clearly as possible the diversity of the whole content.

In addition to the films made on the Western Front, the collection also includes the Soviet documentary Chekhoslovatskaya voynskaya chasť v SSSR (Czechoslovak Military Unit in the USSR; dir. A. Kiryukhina, 1942) – the only original film about Czechoslovak soldiers in the East maintained in NFA collection, whose footage was included in many compilation documentaries in the past.[9] Unlike the other extras, this film was shot by a Russian crew. After the war, the film was given to the Československý filmový ústav (Czechoslovak Film Institute), as well as to the Vojenská půjčovna filmů (Army Film Rental Service), which used some of its sequences in their own propaganda documentaries, which were subsequently censored after February 1948 in order to remove images of then politically undesirable officers. This Soviet documentary is complemented by the newsreel segment Slavnostní přísaha a předání bojového praporu 2. čs. samostatné brigádě (Ceremonial Oath and Handover of the Standard to the 2nd Czechoslovak Independent Brigade), which presents unassembled footage depicting the 2nd Czechoslovak Independent Parachute Brigade in the Soviet Union in 1944.

Another topic concerns the actions of Czechoslovak troops in North Africa. Extensive research has shown that the unassembled amateur film Československá jednotka v severní Africe (Czechoslovak Unit in North Africa, 1941–1943) preserved in the NFA collection is one of the few surviving films dealing with this topic. Due to the critical condition of the film material and the low technical quality of the image, we have decided to supplement the film with period photographs from the Vojenský ústřední archiv (Military Central Archive) and from Jaroslav Čvančara’s priváte collection.

Another part of the edition focuses on important moments associated with the return of Czechoslovak troops to their homeland in 1945. The film Cesta domů (The Journey Home, 1945) documents a Czechoslovak brigade as it goes through training, transport to France, fierce fighting near Dunkirk, and finally the return trip to Prague. Miroslav Tiller, who was officially responsible for film activity in the brigade, had no formal film education and shot this film with a staff of amateur cameramen. The only professional filmmaker among the soldiers of the Czechoslovak army on the Western Front at that time was Kurt Goldberger, who had a signifiant influence on the final form of this work.

An essential component of the end of the war and the liberation of the state were the military parades of the liberators. Thus, the edition includes segments from post-war newsreels depicting soldiers from the Eastern and Western Fronts being welcomed as heroes. Several military parades took place in 1945 and included such figures as General Patton, General Harmon, Field Marshal Montgomery, and, among the distinguished Czechoslovaks, General Alois Liška. Footage from these events also shows the ceremonial, yet also relaxed and joyful atmosphere as the Red Army was welcomed to Prague, as well as the last public presentations of Czechoslovak troops from the West for many years to come.

As a whole, this edition seeks to introduce a new voice to the ever-present debate about the role of Czechoslovakia in World War II. The film materials it contains should serve not only historians concerned with the image of exile army forces, but also researchers working on the topic of national memory and the politicisation of history. The collection is also intended for the general public, especially those who have an interest in depictions of combat activities in Europe.

Iwona Łyko Plos

Notes:

[1] Quoted in: James Chapman, The British at War: Cinema, State and Propaganda. London: IB Tauris 1998, pp. 216–217.

[2] See United Nations: United Nations Day in Great Britain (Ministry of Information, Crown Film Unit, 1942), Parad polskoy chasti (Parade of the Polish Unit; Kuybyshevske studio film-chroniky, 1942), Brazil at War (US Office of War Information, 1943), Fighting Norway (Sydney Newman, National Film Board, 1943).

[3] See Czech Army in England (Gerry Massey-Collier, 1940), Fighting Allies: Czechoslovaks in Britain (Louise Birt, 1941), Liberated Czechoslovakia (Osvobozhdennaya Chekhoslovakiya; Ilja Kopalin, 1945).

[4] See A. J. Liehm, Ostře sledované filmy. Československá zkušenost. Praha: Národní filmový archiv 2001, p. 96.

[5] Jiří Weiss, interview by Elmar Klos, April 8, 1984, Národní filmový archiv, Oral history collection. See also A. J. Liehm, Ostře sledované filmy, p. 97.

[6] Weiss most likely speaks about the version of the film that did not yet include a filmed statement by Minister Hubert Ripka at the beginning.

[7] Věrni zůstaneme. Filmová kartotéka, 1946, no. 6, p. 5. The text by Alena Šlingerová addresses the film in more detail.

[8] Jiří Weiss, interview by Zdeněk Štábla, Pavel Taussig, Václav Merhaut, June 11, 1983. Národní filmový archiv, Oral history collection.

[9] For example, in the Czechoslovak documentary Generál Svoboda (General Svoboda, 1968) and the Russian newsreel Sovremennik (Modernist).