“Nobody here really works with talent. The funny thing is that everyone here praises each other, but beyond our borders nobody knows Czech film. Nowadays, we often read about the catastrophic state of Czech culture. I wrote about this for years, but no one joined in then. Without criticism there is no art.”[1]

Czechoslovak film of the 1960s has been described extensively from many different angles. But we still lack, for example, a comprehensive account of the role of film criticism in the rise of the New Wave. There is just a general belief that its role was significant and that there was a lively exchange of ideas between film theorists and industry professionals. This historiographic gap is understandable. It is difficult to record and quantify the impact that writing about film had on the face of the industry, as many times it consisted of maintaining informal relationships and providing advice and recommendations. For the most part, we remain dependent on the recollections of those who experienced it. Verifiable facts are lost in a thicket of myths.

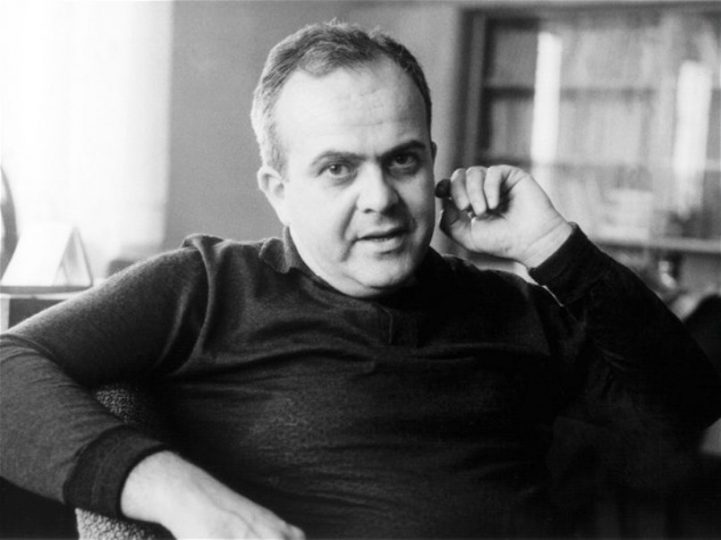

The publicist, dramaturg and public intellectual Antonín J. Liehm (AJL), who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year, was an almost mythical figure of Czech film criticism and the entire intellectual milieu around the Prague Spring. When he died in December 2020, most obituaries automatically hailed his contributions to the flourishing Czech cultural climate of the 1960s. Not only did he think about the local cultural scene in a global context, he also tried to articulate how it might be of relevance to the rest of the world. His writing and public appearances, which resonated abroad, are said to have had a positive impact on the international status of Czech film, literature and theatre.

Most interviews with Liehm published during his lifetime were also written in a spirit of adoration. They are full of quite understandable respect and admiration for the doyen of Czech cultural journalism, who found himself out of favour with the regime at the end of the 1960s and spent the normalization period in exile. Few people dared to question Liehm about the controversial chapters of his journalistic career, which in fact did not begin in the glorious times of political and cultural liberation that he himself most fondly remembered after August 1968 or November 1989, but almost two decades earlier, when Liehm celebrated the cheesy portraits of Stalin and scorned the Zionist conspiracy surrounding Rudolf Slánský. This was one of the main reasons why filmmakers, including those associated with the New Wave, perceived him as a contradictory figure and a model opportunist.

We know who we’re dealing with here

Liehm’s first major journalistic endeavour was the weekly newspaper Kulturní politika, which he began publishing immediately after the Second World War together with his friend, the theatre director Emil František Burian. At only twenty-one years of age, Liehm became the editor, then the managing editor and editor-in-chief of the new periodical. This was published for exactly four years, until the so-called “Nezval case”, when in 1949, a couple of students from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University wrote a dirty parody of Nezval’s The Great Orloj (Velký orloj), called Socialist Love. When the text was published on the pages of Kulturní politika, outraged party apparatchiks interpreted it as an attack on the Communist Party and the Red Army. The affair, investigated by Ministry of the Interior authorities, led to the dissolution of the magazine, or rather its formal merger with Lidové noviny.

But unlike the students, Liehm was not penalised. He was not expelled from the party; he was only reprimanded. Back then he was studying at the Political Faculty of the University of Political and Social Studies in Prague and was already working in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs press department, where he started working as an avid Communist two months after the events of February 1948. He was recruited to the post of liaison officer for foreign journalists by Vladimír Clementis, who was executed in 1952 after the political Slánský show trial. It remains a cruel irony that three days after the execution of Clementis and other prisoners, on 6 December 1952, he wrote in Literarní noviny that “the trial of the anti-state conspiracy centre revealed the full extent of the activities of international Zionist organizations in the service of American imperialism.” He concluded his pamphlet with on a cautionary note: “We know who we are dealing with, and we shall align ourselves accordingly”[2]

Liehm had contributed to Literární noviny since the newspaper’s founding in 1952. Prior to that, he served his compulsory military service at the publishing house Naše vojsko, joined the foreign editorial office of the Czechoslovak News Agency and contributed to Lidové noviny (in 1968, he would briefly become its editor-in-chief). If he wanted to keep his job in the editorial office, he had no choice but to follow the party’s ideological line. He was also pressured by State Security Service (StB), to whom he began to leak information about his colleagues in July 1954 under the code name Tonda.[3] According to a quote from the journalist and documentary filmmaker Adam Drda, his files state that he initially regarded his cooperation “positively and performed his tasks conscientiously”, but according to a later assessment, he did so “out of fear of being in conflict with the Party and his superiors.”[4]

Liehm also wrote strongly socially committed texts about cinematography, on which he focused most of his attention from the second half of the 1950s onwards. The intensity with which he did so was known, for example, to director Jiří Weiss, Liehm’s roommate at one time. But when it came to meeting the standards of socialist realism, their friendship went out the window. Liehm’s criticism of Weiss’s film The Last Shot (Poslední výstřel, 1950) was uncompromising, even crushing. He accused Weiss of being insufficiently ideological, and of being a cosmopolitan following the fashion of British “bourgeois civilism”.[5] Liehm’s objections to Weiss’s children’s film, Doggy and the Four (Punťa a čtyřlístek, 1955), had a similar tone. What bothered him about the story of a group of friends caring for a stray dog was its lack of ideology, an absence of pioneer movement organizations, and how it avoided the big questions of the past and present.[6]

As Weiss states sardonically in his memoirs, Liehm later apologetically explained to him that “such were the times” and he had to carry out his editor’s instructions.[7] In the same book, Weiss presents an anecdote testifying to Liehm’s sudden transformation from an ardent Stalinist to a progressivist. While in the 1950s he allegedly gave everyone The Fall of Berlin (Pád Berlína, 1949) as an example of “the greatest film he had ever seen”, in the second half of the 1960s he referred to the director of the Czechoslovak State Film, Alois Poledňák, as an ideological conservative who should make way for New Wave directors. When Weiss reminded him on that occasion how he had once admired a film glorifying Stalin, he allegedly fell silent.[8]

Closely watched films

In the press, Liehm’s transformation into a supporter of reforms manifested itself in his increasingly frequent references to non-Czech or non-Soviet films. From 1956 onwards, he regularly attended the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, where he made use of his excellent knowledge of English and French (from which he also translated books by Aragon and Sartre) to interview foreign filmmakers. From October 1960, he had his own section in Literární noviny called Cinema and Us, where he covered, among other things, the latest film news from the West and Japan. From 1961 onwards, he regularly reported on the Cannes Film Festival in Literární noviny (he visited the festival for the first time right after it was founded in 1946). Back then, he was already working in the newspaper as a member of the editorial board and head of the foreign and film section.

In addition to his home newspaper Literární noviny, Liehm wrote (mostly) about film for Kino, Film a doba, Večerní Praha, Divadelní noviny and Orientace. He usually dealt with specific films in a broader cultural and political context, setting them in the context of domestic and foreign stylistic or distribution trends, for which he had a particular eye. He also gained respect for his overview of modern art in general. He always understood film as a medium dependent on the surrounding conditions of reality, production and society. Even after the revolution of 1989 he would continue to hold the position that the political establishment was primarily responsible for the fate of film industry. It is hardly surprising that in the 1960s, when film was discussed throughout society and at high political levels, he understood film criticism as a form of “political journalism”.[9]

The harsher Liehm’s criticism of how Czechoslovak films were being managed and the louder his calls for freedom of speech, the more he found himself in conflict with the authorities. For example, his reflection on Jan Němec’s film The Party and the Guests (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966) could not be published in Literární noviny. Even his article On the Long Track, or Thoughts on Romance for the magazine Film a doba did not pass the censorship process, and his interview with Ester Krumbachová for Literární noviny had to omit the following passage “Or when I answered ‘Hi’ to his ‘Hello, comrade’ and answered his subsequent question ‘How are you greeting me?’ with ‘In Czech’. After that I couldn’t get a job for a long time.”10]

Liehm’s stylistic proficiency and ability to think in more general concepts were also evident in his famous interviews with leading personalities of Czech and foreign films. Most students of film studies have probably come across them thanks to the book series Closely Watched Films, which was first published in English and only many years later also in Czech.[11] Liehm outlined his method of conducting interviews in the introduction to The Interview: “The interview, as I understand it, includes also everything I know about the person I am talking to, what interests me and what I am thinking about; it is also the time when the interview took place, and the reader who will read it.”[12] He usually needed to meet the interviewees repeatedly to understand what was typical for their way of thinking. When doing so, he made do with just a pencil and a notepad. Although he always had the resulting text approved, his writing style was consistent and reflected his own personal expressions.

Some of the interviews from Closely Watched Films were originally published in the newspaper Filmové a televizní noviny, where Liehm found authorial refuge after being banned from Literární noviny in 1967. This biweekly, initiated by the Union of Film and Television Artists, was published from 1966 to 1969. For the first issue published on 8 November 1966, he interviewed Miloš Forman and gave it the title “Miloš Forman is Famous”. He later agreed with the senior editor, Otakar Váňa, that it would be good to capture the attitudes of other emerging personalities of Czechoslovak cinema using similar, half-serious titles.[13]

Keeping up with the times

The interviews with Forman, Papoušek, Passer and Chytilová, revealing their way of thinking and what was essential to them, were not Liehm’s only contribution to the formation of the Czechoslovak cinematic miracle. He wrote insightful, usually positive reviews of the films of the new generation – for him, for example, Daisies (Sedmikrásky, 1966) was “a landmark that revealed new possibilities for cinema and made us see it in a new way”[14] – and in many of his articles he attempted to capture the entire phenomenon of young cinema and the parallel reformist efforts.[15] He credited the Czechoslovak New Wave with a high potential to make a breakthrough in Europe.

Liehm also contributed to the formation of the Czech film scene more directly, as one of the dramaturgs of the Barrandov group Šebor-Bor. According to his diaries, Pavel Juráček describes how Liehm came to his office at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to consult him on the script for The Silver Comet (later named Ikarie XB-1) and was met with overwhelming criticism.[16] Later, however, it was Liehm’s belief in his talents as a director and screenwriter, as manifested, for example, by his favourable review of Every Young Man (Každý mladý muž, 1965), that helped him gain confidence. Nevertheless, Juráček remained sceptical of the dramatic ideological transformation of Liehm and other critics of the time, such as Miloš Fiala and Jan Žalman. According to Juráček, the artists of the New Wave were also on good terms with these reviewers because, unlike the aforementioned Weiss, they had not experienced them as ruthless Bolsheviks. For the critics themselves, defending the younger generation meant showing that they were on the right side and keeping up with the times.

For the sake of illustration, we will quote one of Liehm’s answers from a big interview for the newspaper Divadelní noviny in June 2015: “For example, Jan Procházka and Karel Kachyňa were people I respected, but sometimes I thought they made mistakes and that they should have done things differently. Procházka disliked me very much for that, and this caused tension between us. One day at a writers’ convention he made a critical speech. Afterwards, Jiří Hendrych came up to the microphone and yelled at him for his speech. So, I took the floor and reacted in completely the opposite way. Procházka then came up to me and he thanked me very much. From that moment on, I was on very good terms with him and his children.”[17]

Otakar Vávra had a chance to get to know both the old and the new Liehm, who was able to adapt to changing circumstances with the same grace. In his memoirs, Vávra describes him as a leading communist critic, who then made a turn and began to celebrate formally and thematically progressive films inspired by foreign works instead of communist schematism. Nevertheless, he credits Liehm with contributing significantly to his own artistic rehabilitation when he writes about how, after The Golden Queening (Zlaté reneta, 1965), the critics once again embraced him, with “the signal for this being primarily given by A. J. Liehm, who directly praised me.”[18]

Bohumil Šmída, a dramaturg, producer and communist functionary of Czechoslovak film, provides another piece to the puzzle that helps us understand Liehm in his contradictory or variable nature. He recalled the famous film critic as a man who – before he began to promote the work of the younger generation – “was enthusiastic about every Soviet film that was shown in our country in the 1950s, whether it was excellent or just average.”[19] All of these quoted recollections could, of course, be distorted by memory, personal antipathies, and the ideological demands of the time. What we encounter here is the unreliability of the sources when reflecting backstage relations, mentioned in the introduction.

However, the fragments collected here show at least that Liehm was not a man with one role and one face, whose every action and statement would only benefit Czech culture and society. Though he later moved away from Stalinist-type communism to reformist communism, he did not publicly distance himself from the texts that legitimized the totalitarian regime for many years, and he did not want to talk about his cooperation with the StB. Not even after his emigration abroad.

Liehm initially travelled to Paris as a foreign representative for Czechoslovak Film. In the summer of 1969, he decided to remain abroad with his wife Drahomíra, who was also a film critic. In the years that followed, he taught at European and American universities, and in 1984 he founded the cultural and political magazine Lettre internationale in France. In addition, he edited magazines and anthologies and, by organizing various shows, continued to raise the profile of the New Wave and thus kept its cult alive, which in this country, thanks to Liehm’s nostalgic evocation of past eras, would gain in strength again in the 1990s.

When it came to film, his premises remained similar. It remained an essential part of the national culture, and he was convinced that the reform of the film industry had to begin with a transformation of the production conditions. The nationalization of film was, he said, “to give it the possibility of becoming at least partly a form of art that would not constantly have to consider the box office and the market.”[20] It is clear from his reflections and responses that he continued to hope for the introduction of a reformist socialism that would provide a stable production base for filmmakers and ensure every citizen a job, a salary, and also freedom. After the Velvet Revolution and his return to the Czech Republic, Liehm did not accept the transformation of art from a social and political instrument to a form of entertainment and product and was one of the most outspoken critics of the “Americanization of culture” (although he defended selected American filmmakers, such as David Lynch). Young domestic filmmakers in his view, failed to find their own themes and aesthetics.

Such a viewpoint can be considered an expression of elitism, nostalgia or hypocrisy, but it would be a shame to universally reject everything Liehm said and wrote after November 1989. Many of his texts and his overall way of thinking about Czech society and culture remain extremely thought-provoking. To give one example among many, let us conclude with his call for artistic criticism, partly answering the question of what gave criticism such an exclusive position in the 1960s: “Criticism should show that you enjoy writing it and that you are interested in the work. Whether you write about it negatively or positively. It should always be clear from your writing that you are not writing it with bad intentions, but that you feel that way.”[21]

Literature:

Petr Bednařík, Jan Jirák, Barbora Köpplová, Dějiny českých médií: od počátku do současnosti. Prague: Grada 2011.

Robert Buchar, Sametová kocovina. Brno: Host 2001.

Adam Drda, Zamlčovaná minulost A. J. Liehma. Bubínek Revolveru. Available online: <https://www.bubinekrevolveru.cz/zamlcovana-minulost-j-liehma> [quoted 5th August 2024].

Pavel Juráček, Deník III. 1959–1974. Prague: Torst 2018.

Jiří Knapík, Martin Franc, Průvodce kulturním děním a životním stylem v českých zemích 1948–1967. Prague: Academia 2011.

Jan Gruber, Lukáš Rychetský, Radostná hra s cizím psaním. S publicistou Antonínem Jaroslavem Liehmem o „dělání novin“. Advojka.cz. Available online: <https://www.advojka.cz/archiv/2014/19/radostna-hra-s-cizim-psanim?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR1uMV9SWmmgdpNEHMiaX4PPXHIhb0qsxoXKHxqCXOIMpGSzucFNq6DjGRM_aem_2qv1ng32xb8wL1JBPxYTPQ> [quoted 5 August 2024].

Hulec, Vladimír, Hledání v paměti (Velký rozhovor s A. J. Liehmem). Divadelní noviny. Available online: <https://www.divadelni-noviny.cz/hledani-v-pameti-velky-rozhovor-s-a-j-liehmem> [quoted 5th August 2024].

Antonín J. Liehm, Minulost v přítomnosti. Brno: Host 2002.

Antonín J. Liehm, O věcech se musí mluvit nahlas. Brno: Host 2024.

Antonín J. Liehm, Ostře sledované filmy. Prague: Národní filmový archiv 2001.

Antonín J. Liehm, Rozhovor. Prague: Československý spisovatel 1966.

Slovník české literatury po roce 1945. Available online: <https://slovnikceskeliteratury.cz/> [cit. 5th August 2024].

Bohumil Šmída, Jeden život s filmem. Prague: Mladá fronta 1980.

Kamila Trojanová, Kulturní publicista A. J. Liehm. Diplomová práce. Prague: Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Fakulta sociálních věd 2013.

Otakar Vávra, Podivný život režiséra. Prague: Prostor 1996.

Jiří Weiss, Bílý mercedes. Prague: Victoria Publishing 1995.

Notes:

[1] Jan Gruber, Lukáš Rychetský, Radostná hra s cizím psaním. S publicistou Antonínem Jaroslavem Liehmem o „dělání novin“. Advojka.cz. Available online: <https://www.advojka.cz/archiv/2014/19/radostna-hra-s-cizim-psanim?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR1uMV9SWmmgdpNEHMiaX4PPXHIhb0qsxoXKHxqCXOIMpGSzucFNq6DjGRM_aem_2qv1ng32xb8wL1JBPxYTPQ> [quoted 5 August 2024].

[2] Antonín J. Liehm, Sami se odhalují. Literární noviny 1, 1952, issue 44, p. 2.

[3] In his memoir The Past in the Present (Minulost v přítomnosti), Liehm quite understandably does not mention this fact. He does not forget to mention, however, that when he went to foreign film festivals, the StB kept an eye on him.

[4] Adam Drda, Zamlčovaná minulost A. J. Liehma. Bubínek Revolveru. Available online: <https://www.bubinekrevolveru.cz/zamlcovana-minulost-j-liehma> [quoted 5th August 2024].

[5] Antonín J. Liehm, Poslední výstřel – neúspěch velkého tématu. Lidové noviny 58, 1950, no. 184 (8. 8.), p. 5.

[6] Antonín J. Liehm, Děti vůbec a děti naše. Literární noviny 4, 1955, no. 21, p. 4.

[7] Jiří Weiss, Bílý mercedes. Prague: Victoria Publishing 1995, p. 99.

[8] Same source, p. 99 and 101.

[9] Antonín J. Liehm, Ostře sledované filmy. Prague: Národní filmový archiv 2001, p. 17.

[10] Kamila Trojanová, Kulturní publicista A. J. Liehm. Diplomová práce. Prague: Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Fakulta sociálních věd 2013, p. 40.

[11] In addition to filmmakers, Liehm also liked to talk to writers and intellectuals, such as in his book Generation (Generace), where he talks to Václav Havel, Josef Škvorecký and Milan Kundera. Antonín J. Liehm, Generace. Prague: Československý spisovatel 1990.

[12] Antonín J. Liehm, Rozhovor. Prague: Československý spisovatel 1966, p. 12.

[13] Liehm also dedicated a separate book, The Miloš Forman Stories (Příběhy Miloše Formana), directly to Forman, which he based on a conversation they had during the first years of the filmmaker’s stay in the United States.

[14] Antonín J. Liehm, Sedmikrásky. Literární listy 1, 1968, no. 5, p. 10.

[15] Např. Antonín J. Liehm, Není zázraků. Orientace 4, 1969, no. 2, pp. 85–91; Antonín J. Liehm, Bilance zázraku, Literární noviny 16, 1967, no. 16, p. 3.

[16] Pavel Juráček, Deník III. 1959–1974. Prague: Torst 2018, p. 184.

[17] Vladimír Hulec, Hledání v paměti (Velký rozhovor s A. J. Liehmem). Divadelní noviny. Available online: <https://www.divadelni-noviny.cz/hledani-v-pameti-velky-rozhovor-s-a-j-liehmem> [quoted 5th August 2024].

[18] Otakar Vávra, Podivný život režiséra. Prague: Prostor 1996, p. 237.

[19] Bohumil Šmída, Jeden život s filmem. Prague: Mladá fronta 1980, p. 266.

[20] Robert Buchar, Sametová kocovina. Brno: Host 2001, p. 5.

[21] Vladimír Hulec, c. d.