If we look for Czech traces in films by Alfred Hitchcock, we discover several characters of Czech origin (Czech-American John Kovac in Lifeboat (1944), Doctor Hartz from Prague in The Lady Vanishes (1938) and at least two actresses of Czech Origin. Kim Novak, who portrayed the mysterious Madeleine in Vertigo, was born in Chicago but her unusual surname is the heritage of her Czech ancestors. The birthplace of Anny Ondráková was the Polish town of Tarnov, but both of her parents were Czech. Her collaboration with Hitchcock made her the arguably most famous personality of Czechoslovak silent cinema.

Ondráková started her film career when she was 17 years old. Most frequently, Ondráková starred in films by Jan S. Kolár and her partner Karel Lamač (e.g., The Poisoned Light (Otrávené světlo, 1921), The Lumberjack (Drvoštěp, 1923) and White Paradise (Bílý ráj, 1924). Together with Lamač, she also ventured into business through the companies KALOS and Ondra-Lamac-Film. Soon enough, she started to star in German and Austrian films as Anny Ondra. She also appeared in popular situational comedies made by the production company Sascha-Film, founded by Czech automobile racer Count Alexander “Saša” Kolowrat.

After a few years of starring in various European productions, Ondráková became an international star whose fame outgrew the possibilities of our market. Projects planned by the Degl brothers had to wait, as in December 1927 Ondráková signed a contract with the British company First National. As Anny Ondra, she was twice directed by Graham Cutts and twice by his talented assistant, Alfred Hitchcock. Apparently, she must have impressed him on the set of one of the playful comedies she filmed with Lamač in Berlin studios. But Hitchcock cast her in more serious roles.

The first role was in The Manxman (1929), an adaptation of a Victorian novel about passion and betrayal set in a fishing community on the Isle of Man. Ondráková portrayed the emotionally torn daughter of a harbour innkeeper. The young woman haunted by guilt is one of the protagonists of an unfortunate love triangle. During filming, Ondráková lived in a house with Hitchcock and his wife Alma. That’s probably where her life-long friendship with the Hitchcocks was forged.

In an interview with François Truffaut, Hitchcock said The Manxman was his last “silent one.” In reality, he made one more silent film, an adaptation of a play by Charles Bennett. The thriller Blackmail (1929) was originally made as a silent film, but it was later partially reshot with sound and premiered as the first British sound film. However, cinemas without sound equipment screened the silent version, which – to make things more complicated – included several scenes filmed during the reshoot.

Because of its innovative usage of music and sound, expressionist mise-en-scène, and rhythmical montage reminiscent of urban symphonies by Walter Ruttman and Dziga Vertov, Blackmail is considered to be a fundamental work of Hitchcock’s early career. At the same time, it includes many motifs and narrative procedures that are now attributed to Hitchcock: a blond damsel in distress, death by stabbing, fleeing from the law…

Ondráková portrayed Alice, a woman who in self-defence stabbed a man who tried to rape her. Her fiancé is charged with the investigation. In the opening eight minutes of the film, there are no dialogues, the characters open their mouths but no words come out. The whole sequence of apprehension, interrogation, and incarceration, accompanied by non-diegetic music, creates the impression that we’re watching a silent film.

The director’s artful work with sound technology is manifested also in the very first dialogue we hear. It doesn’t deal with anything important; it’s a seemingly accidentally overheard conversation of two men standing with their backs to the camera – Hitchcock used this to elegantly tackle the issue of imperfect synchronisation of image and sound common for early sound films.

The film includes several examples of inventive work with sound. A textbook example is one of the first instances of sound bridge and subjectively perceived sound (emphasising the word “knife”, which Alice hears another character say).

The lead actors stick to expressive acting from silent films, but in some scenes, sound enhances their performances. A good mood is expressed by whistling a jolly melody, laughter doesn’t have to be accompanied by exaggerated gestures, the state of mind of the heroine haunted by guilt is mirrored in a crowd laughing on the street…

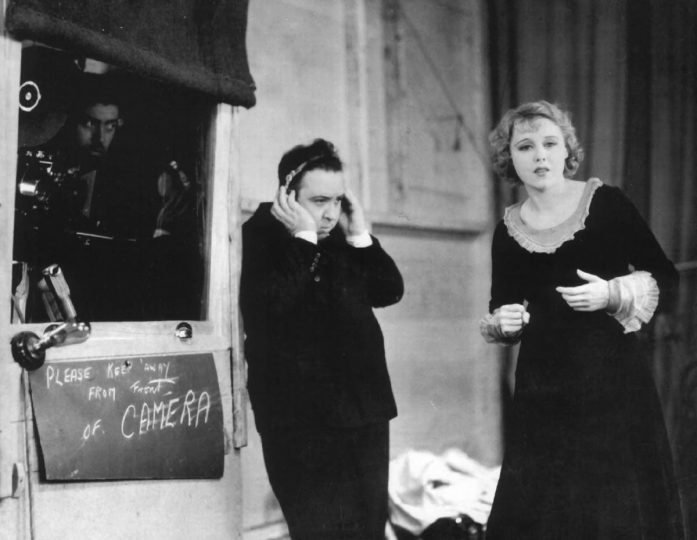

Unlike the result, the production itself was a bit problematic. The film was originally made as a silent film, and Ondráková wasn’t supposed to talk in front of the camera. But the problem wasn’t her insufficient language skills. In her later films, she had no trouble speaking or even singing in German or French. She just didn’t have a chance to prepare for English dialogues with a cockney accent as the role demanded. Her attempts can be seen in a short sound film titled Sound Test for Blackmail capturing Ondráková joking around with Hitchcock during sound tests.

Because of the absence of dubbing studios, the crew had to come up with a solution directly on the set. Hitchcock refused the producer’s suggestion to recast the actress with an unsuitable voice. He became fond of her, and she was the type he wanted in the film. He therefore hired her English colleague, Joan Barry. During filming, she stood away from the scene and read the lines into a microphone, while Ondráková only lip-synced. But this fact didn’t do any harm to her performance in the eyes of reviewers. A review in Variety from 1929 praises her acting by saying that “Ondra is excellent as the girl”.

In any case, Blackmail marked Anny Ondráková’s end in British cinema. She returned to Germany, left Lamač, and married boxing champion Max Schmeling, with whom she stayed until her death. The Hitchcocks apparently visited her every time they were in Germany. In return, she sent them cards every Christmas.