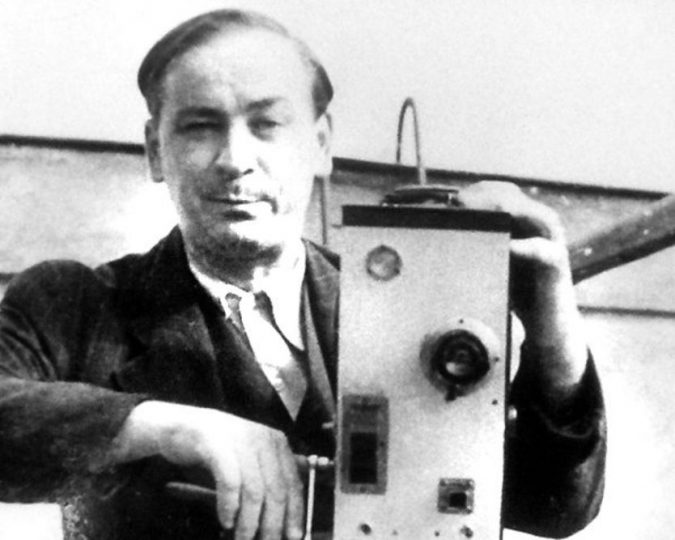

Film collector, restorer, and amateur filmmaker Bohumil Veselý (1903–1971) was an unforgettable figure of Czech film archivation who was sadly not very well-known by the general public. His passion for film can be traced back to an injury he suffered when he was six years old. He was hit by a horse-drawn carriage and his left leg had to be amputated.

For the rest of his life, Veselý used a prosthetic leg and harboured a grievance. Because of his invalidity, he quickly became an outsider. He was bullied, couldn’t fit in, and kept to himself. To compensate for the lack of social and sporting activities during puberty, the young loner became absorbed in film.

He frequented cinemas, read film magazines and from the 1920s also collected everything related to the relatively new invention. In addition to photographs, cuttings, autographs, various film apparatuses and later also phonographs with music from the first sound films, he managed to gather an admirable quantity of complete films and various footage which he used to compile thematic showcases (focusing for instance on sport, arts, film stars…). He was, in all probability, the first serious film collector here.

Although Veselý constantly struggled with a feeling of his own inferiority, he was an exemplary student and employee. His employers praised his diligence and thoroughness. After successfully finishing primary school in Prague and subsequently also a private Business Academy, where he learned accounting and German, he worked in about a dozen jobs between 1921 and 1935,

He worked mostly as an assistant for various film studios (Universal-Film, Biografia, Elektafilm). When film rental companies discarded worn out films, Veselý systematically salvaged them for his own collection. He also worked as a projectionist and that helped him to organise private screenings for his neighbours and artists in his own apartment. He later learned how to preserve and restore film material and became a sought-after intermediator of domestic trade with films and film equipment.

In addition to a private cinema and archive, Bohumil Veselý also had a museum of film curiosities. As he probably wasn’t employed anywhere after 1935, these activities represented the main source of his modest income.

Thanks to his language skills, he was able to sell films to Germany and before the Protectorate was established, he came into contact with the German Reichsfilmarchiv in Berlin. He cooperated with the archive even during the occupation. In a letter to his friend, Veselý defended doing business with the occupants by mentioning that Berlin appreciates his films more and can take better care of them.

When Jindřich Brichta laid the foundations of the Czechoslovak Film Archive in 1942, he offered a job to Veselý. As a film enthusiast, he refused the offer because he perceived a professional archive institution as his competition. His fear of losing his collection led to his confrontational behaviour and a tense relation with Brichta who was aware of the extraordinary extent and value of Veselý’s collection which allegedly contained over 300 thousand meters of film and naturally wanted to have the pioneer of Czech film archivation on his side.

Brichta partially succeeded in December 1947 when Veselý accepted his offer to become a part-time external employee of the archive. Due to the nature of his handicap and other health issues, he could take care of film copies and identify recordings from the comfort of his home. And thanks to the equipment he had in his apartment in Školská 38 in Prague, there were no further obstacles for him to do just that.

Veselý invited prominent personalities of Czech culture to his apartment where he filmed their short profiles. He expanded his exceptionally extensive film collection by several hundred of his own amateur films creating a unique gallery of important figures such as Konstantin Biebl, Jaroslav Seifert and Kamil Lhoták. Digitalised versions of these profiles are now accessible in the LINDAT repository.

Silent micro-portraits no longer than several dozen seconds share the same style: the invited person comes to a courtyard balcony, turns around to face the camera and poses at the railing. For a voluntary admission, Veselý invited people to see these original films which were not available elsewhere and whose value is documentary rather than artistic. However, he didn’t tax this income and that gave the Communist regime a pretence to imprison him for a year in late 1950s.

Veselý, in fact, already had an encounter with the Communists shortly after their rise to power in February 1948. In October 1949, two State Security agents came to search his apartment where he allegedly kept pornography. After four hours of coercive interrogation at the headquarters of the State Security in Bartolomějská street, Veselý confessed that he really kept a few “indecent” films in the attic. The incident triggered a further investigation and Veselý’s entire collection eventually ended up in the hands of the film archive. This was presumably the primary impulse to conduct the house search.

The rightfully bitter and frustrated collector “officially” sold his collection of more than 1000 boxes full of films to the state institution but before he received the agreed sum, a monetary reform was conducted in 1953. As a result, Veselý only received a fraction of the promised amount.

Despite this, Bohumil Veselý stayed in the Archive. He was officially let go shortly before his retirement in 1964 because of alleged unreliability, misconduct, and bad relations with his colleagues.

The man with a complicated life and personality who was responsible for preserving a great many unique films and shots died six years later in 1971. He left everything to his wife Marie.

Sources:

Luboš Bartošek, Filmový kalendář 1973. Praha: Tisková služba ÚPF 1973.

Jindřich Schwippel, Veselý Bohumil (1903–1971). Inventář NFA 2010.

Jan Trnka, Český filmový archiv 1943–1993. Praha: Národní filmový archiv 2018.

Digitalised films of the Gallery of Personalities and Filmmakers were published in the LINDAT repository with the support of the LINDAT/CLARIAH-CZ (č. LM2018101) project financed by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.