On 15 December this year, Evald Schorm, the film, stage and television director who was unafraid of asking his audience questions without simple answers, would celebrate his 85th birthday. He was an existentialist philosopher and a great moralist of the Czechoslovak cinema's New Wave.

„Everyone around Evald had one thing in common. When they had him around, they felt uplifted; his presence inspired security, confidence, honest self-respect, admiration for life, as well as strong and unescapable awareness that there was something above us that brought humility and respect to our neighbours, whose faith is ours. [1] (Jan Kačer)

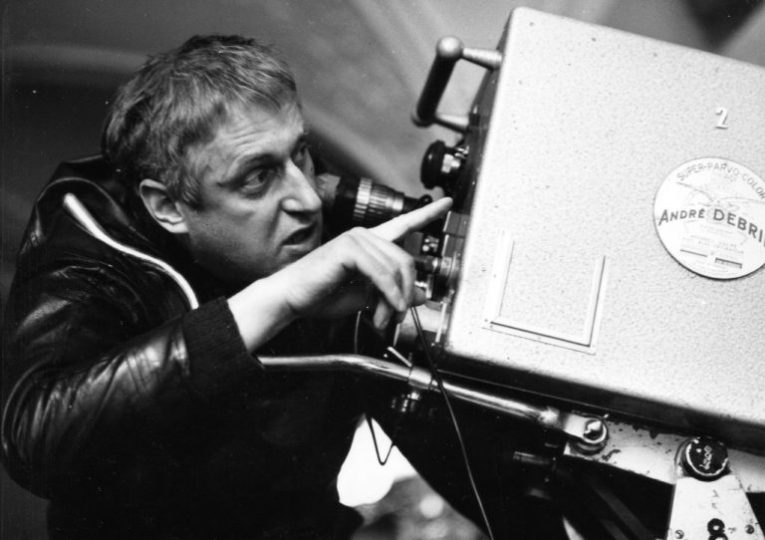

When chosing actors for his film parable A Report on the Party and the Guests/O slavnosti a hostech (1966), director Jan Němec reportedly applied the criteria of certain character traits for each of the roles. Evald Schorm was cast in the role of a taciturn husband, a convinced individualist, standing aside with his sad face, doubting the point of the whole event only to eventually leave the party prematurely. He is the only one to show a character strong enough and a taste sufficiently refined to know right from wrong, to be able to defy the group and refuse to play a game he loathes. This man, habitually wearing a beret, a leather jacket and corduroys, was for many an incarnation of decency and humility. He made his colleagues feel important, he gave them the conviction it is them who constitute the quality of his works. When directing, he never ordered, always encouraged. Similarly, his films do not preach, they ask questions and they inspire.

Although his birth certificate states Prague is his place of birth, Evald Schorm spent most of his childhood in the countryside. His mother arrived to the maternity hospital in Prague from an estate in Elbančice, a village on the border of central and southern Bohemia. Not far from Elbančice, there is the town of Mladá Vožice, where Evald went to primary school. During his childhood years, his regular attendance at Sunday masses shaped Schorm’s warm attitude towards Christianity. Although he had not remained a practicing Christian, his faith always constituted an integral part of his life and work. Schorm left the countryside at the age of 14, when he took up studies at the Higher School of Economy in the town of Tábor. There, he later met his first, and until his death also the only, wife, Blanka Dolejšová (they got married in 1954), who was also the mother of his son, Oswald (1961). After being expelled in the senior year as a son of a „kulak“ (the communist regime’s derogatory designation of farm owners) during the onset of the stalinist era, and after the confiscation of their family farm by the state, Schorm and his parents moved to Zličín near Prague. Later, he was allowed to pass his final exams after all, which allowed him to find temporary employments as an accountant, a tractor driver or a construction worker. In 1954, having completed his obligatory military service, he became a singer at Army’s Art Company lead by Vít Nejedlý. The young man dreamt of a career as an opera singer. That was why he sought admission at the The Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. In 1956, he was finally admitted by the Academy, but not to the Theatre Faculty, but the Film Faculty. Between 1957 – 1962, he was a student in Otakar Vávra’s film directing class alongside Věra Chytilová, Jiří Menzel or Jan Schmidt. In the dramaturgy and screenwriting classes, Antonín Máša or Pavel Juráček were his classmates. The latter noted in his diary that except Schorm, there was probably „not one talented and conscientious person.“ [3]

During his FAMU studies, Schorm directed short feature film exercises Who can’t take their heaven/Kdo své nebe neunese (1959) and Autumn 1945 [4] For the school magazine Žurnál FAMU: První občasník he made short Kostelník/Sacristan (1961), elaborating on a story of a sacristan stealing from the church’s donation box. He graduated with restrospectively narrated Turista/Tourist (1961), introducing the first of a series of his typical uprooted heroes who are prevented from living a fulfilled and honest life both by their personal characteristics and the outer circumstances. The part of the alcoholic who despises himself as much as he is despised by his surroundings, was played by Vlastimil Brodský. Antonín Máša was the author of the script. Both artists later worked with Schorm on his full length films Courage for Every Day (Každý den odvahu,) and End of a Priest (Farářův konec). Shorm later directed several dramatic texts by Máša on the stage of Laterna Magika, a theatre combining live actors‘ performances with film projections,

While still a student at FAMU, Evald Schorm gained his first real life experience in Barrandov studios, where he worked on Zdeněk Podskalský’s Spadla s měsíce (She Fell off the Moon, 1961), as a lighter and one of the director’s three assistants. After his graduation, Evald Schorm started working in the Studio of documentary film as a news co-author and he gradually worked his way up to the post of a documentarist. After some time, however, he returned to FAMU and betwenn 1966-1971, he worked there as an assistant professor at the directing department under Václav Wassermann and Otakar Vávra.

„I like working on documentaries, because they make you see the context. By context, I don’t mean causes and consequences, but connections like understanding, sense for underlying core of things and for the path that leads to it. Even the most careful explicitness must be useless, because reality is always deeper and more complex. „[5] (Evald Schorm)

Evald Schorm first work of non-fiction was Blok 15 (1959)., a news report celebrating with the obligatory grandiloquence the exertion of concrete workers during the construction or the Orlík Dam. After the concrete workers, Schorm next paid a film tribute to the toils of gravel workers in Země zemi (Soil to soil, 1962: his first collaboration with cameraman and documentarist Jan Špáta), loggers in Stromy a lidé (Trees and men, 1962) and railway workers in Železničáři (Railwaymen, 1963) The last mentioned film was awarded with the Bronze medal at the 14th International Documentary Festival in Venice for its unconventional depiction of a working environment, according to Jan Bernard similar to the classical British documentary, Night Mail (1935),[6]. Schorm is also stated as the director of Helsinky (Helsinki, 1962) about the 8th World Festival of Youth and Students. In reality, he only edited the material shot by Polish filmmakers and Jiří Volbracht from the Czechoslovak Television. Althought the subject of the before-mentioned films was imposed on creators from „on high” (Trees and men, for instance, was an assignment from the Ministry of Economy), Schorm was able to surpass the task and create timeless essays. Besides the human toil, he took interests in other things, too: he was asking himself about the purpose of the hard work and its benefits for both the society and the individual.

Similarly to how Schorm’s first documents make a contrast between veristic records of working people and lyrical views of nature accompanied with poetic voiceovers, Schorm himself was interested in the work of not only blue-collar workers, but also artists. Jan Konstantin, zasloužilý umělec (Jan Konstantin, Artist of Merit, 1961) is a portrayal of the National Theatre’s opera singer, showing the balance between artistic activity and the artist’s active rest. Žít svůj život (Living Your Own Life, 1963) shows the work of Czech photographer Josef Sudek, using not only his photographs, but also shots fashioned according to his photos and co-authored by Jan Špáta. It was thanks to Špáta and composer Jan Klusák that Schorm’s best documentaries were accompanied by captivating audiovisual symphonies, rebelling against the convention of documentary exposés from the stalinist era, often undistinguishable from propagandist weekly news reports due to their lecturing tone, authoritative commentaries and repeated stereotoypes. [7]

Schorm’s sociological survey Proč? (Why?, 1964) is definitely one of the highlights of his work, opening the thorny subject of a declining birth rate and a rising number of abortions (according to the film, half a million abortions were carried out in Czechoslovakia between 1958 and 1963). Schorm and Špáta interrogated married couples, women at work or doing shopping, railwaymen and retired people. What they wanted to know was why so few children were being born. The authors do not judge or argue with their respondents. All answers are accepted as evenly important and none is deemed definitive. It is therefore up to the audience to answer for themselves the question from the film’s title, based on the information they get. Besides unveiling the regime’s incompetence to create dignified conditions for a happy life (where existence would no longer be considered a burden), the documentary also captures attention with its style, inspired by French cinéma-vérité. We are aware of the presence of the camera that the social actors respond to, the film was shot „in the field“ instead of artificial studios, with the emphasis on spontaneity and capturing raw reality. In his book on Czechoslovak documentary film, Antonín Navrátil summarizes the starting points and objectives of the new wave in documentary film, represented not only by Schorm and Špáta, who was, among other creators, the most consistent one to develop the tradition of Schorm-like reflexive documentary essay, but also by Karel Vachek and Vít Olmer:

“At that time, there emerged a need of such a documentary film that would abide by the philosophical stance of the creator, a documentary film that would reflect reality and make others reflect it, a documentary film that would not just take notice of reality, but also analyze it.“ [8] (Antonín Navrátil)

Schorm took similar approach as in Proč?, winner of the Trilobit award, in his Zrcadlení (Reflections, 1965), a meditative essay on the phenomenon of leaving, the inevitability of death and the unceasing search for a meaning of life; a film complementary to the preceding survey about birth. Besides gravely ill patients, we see and hear doctors, nurses or youths who had attempted suicide. Each one of them provides a personal view of the elementary questions about human existence. It is again the audience’s call to choose which of the stances is closest to them and to carry on with the reflections after the end of the film. The film gives voice not only to the interviewed, but also to verses by Vladimír Holan, that also gave the film its title, read by Jan Kačer. The poem works with the idea that extreme life situations are a starting point to begin questioning what we thought was granted (an idea confirmed by some of the respondents). [9] Zrcadlení also won the Trilobit award and the Bronze Medal at the XVI. International Documentary Film Festival in Venice, the Special Prize of the Jury at the 7th Days of Short Film in Karlovy Vary, and the main prize at the 3rd International Short Film Festival in Krakow.

„I do have a rather pessimistic view of reality, but not to the extent to moan about it. I try to keep the ability of self-irony, I don’t want to make tearful dramas. It is tragic enough that in our narrowmindedness, all of us consider ourselves far more important than we are.“[10]

While in documentaries, the censorship more or less tolerated subjects contradicting the cheerful socialism-building spirit of previous years, in featured films, there was no possibility to hide behind a newly-awaken interest in sociology and to make films pass for a tool of public opinion research; expressing pessimistic views therefore bore far greater a risk for the creators.

Shorm made Zrcadlení in the same year as his Odkaz (Legacy) and Žalm (Psalm). The former was commissioned by the Czechoslovak Airlines in order to popularize Greek destinations. The latter, an uncommented cut of footage from Jewish cemeteries and a synagogue, was also an assignment, this time for the Commission for Film Promotion Abroad. Carmen nejen podle Bizeta (Carmen Not Only According to Bizet, 1968) is another film usually cited among Schorm’s documentaries. It presents an anarchistic and playful half-an-hour digest of the parody on Bizet’s Carmen staged in Studio Ypsilon in Liberec. Schorm’s next documentary was made for the Short Film company at the occasion of the 80th anniversary of Czech Philharmonic in 1976. The result, Etuda o zkoušce (Study of a Rehearsal) was a portrait of conductor Václav Neumann. Following the opening shots, presenting the musicians‘ preparations before a rehearsal of the first movement of Beethoven’s Symhony no. 5 and the conductor’s reflection on the meaning of music, we see a ten minute long shot, motionless and uninterrupted, yet vibrant with energy, showing Neumann conducting the orchestra. Etuda o zkoušce was awarded the Silver Bear for the best short film at the Berlin International Film Festival.

The 30 minute documentary Zmatek (Confusion) is accompanied by an unusual copyright information (1968-1990). It presents an illegal collection of footage from the days and months following the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops to Czechoslovakia, shot by Stanislav Milota, Jiří Macák, Josef Ort-Šnep and Ivan Vojnár. Zmatek shows unrests in the streets of Prague and also the extraordinary 14th convention of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. The cut made by Schorm in cooperation with Vlasta Styblíková is accompanied by the themes of Tchaikovski’s Swan Lake. We would never be able to see Zmatek if it were not for the then Barrandov Film Studio director Vlastimil Harnach’s protection and the Film Archive director Myrtil Frída’s hiding of the film coils in the depository of the film archive in Štěchovice, labelled as discarded, „confused“ material (hence the ambiguous title „Confusion“) [12].

Schorm’s typical originality of form, or at least his depth of thought, were the trademark of his TV productions, too. Having directed a few songs for music programmes (including the playful collage Gramo von balet, 1966, see also below), he made a conversational mini-comedy based on Maurice Brering’s play The King and the Woman (Král a žena, 1967), in which Jan Werich was king Henry VIII and Jana Brejchová his sixth and last wife, Catherine. Most of the film shows both characters having breakfast in the royal bedroom. Rozhovory (Dialogues, 1969) presented a similarly intimate atmosphere based on conversations between a man sentenced to death (Eduard Cupák) and his judge (Jan Kačer). A reflection of the volatile character of law and justice contained direct references to fabricated political trials from the early 1950s and indirect comments on the situation in the country following the Soviet invasion, which had proved that right is on the side of whoever is the strongest. The story unfolds in an undefined space-time continuum and is interspersed with footage from the editing room, where the director’s character (Miroslav Macháček) tries to prove the changeability of the notion of justice, quoting various reference books and remembering what court practice had been like in the past. Rozhovory was soon banned and could only be broadcasted again in 1993. That was also the fate of the Koncert pro studenty (Concert for Students, 1969) music show, confronting the greatness of music and the pettiness of crimes committed by people. Despite the film’s apolitical character, the television’s leadership understood it as a criticism of the Soviet presence in the Czechoslovak territory.

As for the Gramo von Balet film, influenced by op-art and resourcefully combining cutout animation with live actors, its co-creator, painter and set designer Miloš Noll, described its creation in an interview made at the time: „Evald does not like revue, neither do I, and so we thought we could get the whole thing to another level, that of a fantastic world. That would create something new, something, that is not exactly revue, but that has something in common with it in a sense. We wanted to create a sort of a play. Not a dramatic play, but children’s play, like when kids play duck, duck, goof or blind man’s buff, like when they have a cord, they look at it and think of what it could be, what they could pretend it to be. That means: a train engine, a crane, or even daddy, if we go to extremes. We didn’t take a cord, we took a girl that we disintegrated, and the round stuff we got, we played it on a gramophone. It’s not surrealistic, or dadaistic, it’s rather poetic. A poetic play, a search, an anticipation where it’s going to take us, what and where is going to inspire us to let us go on.“[13]

Křepelky (Quails, 1969), is one of Evald Schorm’s less known TV films. It is a rural insight into the life of working-class youths with off-camera commentary read by Iva Janžurová. Its subject is reminiscent of Věra Chytilová’s Pytel blech (A Bagful of Fleas, 1962). For political reasons, Přemysl Prokop had to be stated as the author of the film. A year later, Schorm directed the TV film Lítost (Regret, 1963), written by Jiří Hubač, exploring the relationship of a hypocrite father (Rudolf Hrušínský) and a son (Jan Hrušínský) trifling with his life. It is a grim picture of bourgeois society made of unscrupulous individuals with no authorities worth following. It was banned shortly after its release and could not be screened again until 1990. Besides Schorm’s scepticism, the ban was in part probably also due to the participation of Vlasta Chramostová, who played the passively on-looking mother. In the early 1970s, Schorm was able to finish a few more TV productions, including Sestry (Sisters, 1970), a study of failing family communication, based on a story by Iva Hercíková; a musical programme Z mého života (From My Life, 1971), and two more dramas, Lepší pán (A Better Gentleman, 1971) and Úklady a láska (Intrigue and Love, 1971)[14]. The latter two were banned right after their release on Christmas Day 1971 on the incentive of communist leader Vasil Biĺak. [15]

„You need to have at least a few places where you feel secure and supported. Most people build a support system in the mediocrity of their lives, they try to avoid all „snags“ and die under a quilted blanket, as Meyerhold used to say. But it’s all far more complicated than that. „[16] (Evald Schorm)

(Continue reading here.)

Notes:

[1] Lukeš, Jan, Lukešová, Ivana (eds.), Mlčenlivý host Evald Schorm. Plzeň: Dominik centrum s. r. o., 2008, p. 27-28.

[2] Also his role of chaplain seeing to hotel guests‘ devotion to God in Antonín Máša’s allegoric Hotel pro cizince (Hotel for Strangers, 1966) can be considered autobiographical. Jan Žalman believed that had Schorm lived in in the Middle Ages, he would have most probably become a religious reformer. See in Žalman, Jan, Umlčený film: Kapitoly z bojů o lidskou tvář československého filmu. Praha: Národní filmový archiv, 1993, p. 65; the fate of Evald Schorm and other prohibited authors also served as an inspiration for Máša’s Byli jsme to my? (Was It Us?, 1990), telling a story of a stage director trying to get around censorship at the time of oppression. Máša dedicated the film to Schorm and Pavel Juráček.

[3] Juráček, Pavel, Deník (1959-1974) Praha: Národní filmový archiv, 2003, p. 231.

[4] Neither of the films has survived.

[5] Janoušek, Jiří (ed.), 3 a 1/2 podruhé. Praha: Orbis, 1969, p. 19.

[6] Bernard, Jan, Odvaha pro všední den. Evald Schorm a jeho filmy. Praha: PRIMUS, 1994, p. 15.

[7] Jan Klusák was the composer for a number of Schorm’s medium-length films, documentaries and TV films, he also composed the music for Návrat ztraceného syna (The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1966) and the biblical parable Den sedmý, osmá noc (The Seventh Day the Eighth Night, 1969). He often combined his original music with compositions borrowed from both modern and classical composers. In Farářův konec (The End of a Priest, 1968), for instance, he underlined the hybrid genre of the film using music of many different styles and genres at the same time. In the film, the music is heard from loudspeakers and radios.

[8] Navrátil, Antonín, Cesty k pravdě či lži. 70 let čs. dokumentárního filmu. Praha: Akademie múzických umění, 2002, p. 242.

[9] It was Holan’s poem Zrcadlení (Reflections) that had supposedly inspired Schorm to make the documentary, when it had helped him to find new will to live during his illness.

[10] Hepnerová, Eva, Návrat ztraceného syna. Kino, 1966, vol. 21, no. 26 (29 December), p. 3.

[11] The actors from Carmen were subsequently cast by Věra Chytilová in her biblical parable Ovoce stromů rajských jíme (We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, 1969).

[12] See the memory of Jaromír Kallista in Lukeš, Jan, Lukešová, Ivana (eds.), Mlčenlivý host Evald Schorm. Plzeň: Dominik centrum s.r.o., 2008, p. 18-19.

[13] -vm-, Gramo von balet. Kino 1967, vol. 22, no. 7 (6 April), 9. [8].

[14] TV records of Sestry and Lepší pán were deleted in the late 1970s. See Bernard, Jan, Odvaha pro všední den. Evald Schorm a jeho filmy. Praha: PRIMUS, 1994, p. 144.

[15] It was probably that exact TV drama made for Slovakian television, where political intrigue interferes with the relationship of a young couple, or rather Biľak’s peevish reaction to it, that contributed to the definitive prohibition of Schorm’s work for both film and TV.

[16] Hepnerová, Eva, Návrat ztraceného syna. Kino 1966, vol. 21, no. 26 (29 December), p. 3.