„I think that in the next few years, people like Čech, Josef Mach, Steklý, Balík, Vorlíček, Lipský, Brynych, Polák, Skalský, Hanibal, Ivo Novák, etc. will have the main say, the key importance and priority at Barrandov,“ Pavel Juráček wrote in his diary in December 1970, during the period of the upcoming normalization. His bitter sigh turned out to be prophetic. The 1960s were over, and with them the artistic bloom they generated. The focal point of Barrandov’s dramaturgy were once again average, unremarkable jolly dramas, crime dramas and agitprops, whose norms in post-war Czech cinema were anchored by the above-named men.

Juráček’s opinions were often unnecessarily harsh, but when we look at Josef Mach’s filmography, we find that he was not really a filmmaker who stood out. He was reliable in doing the work he was assigned. This was his strength, and thanks to it he was able to film without any problems in different times, countries, under various regimes and using diverse genres – from the Third Czechoslovak Republic to late socialism, from Prostějov to Babelsberg, from slapstick comedies to espionage films. Born in Prostějov on 25th February 1909, he would later go on to win the State Prize. Nearly sixty years later, he would direct one of the greatest hits of East German cinema, the western The Sons of Great Bear (Die Söhne der großen Bärin, 1966), at the Babelsberg film studios.

After completing his studies at grammar school in Prague, Mach worked as a journalist and actor at the Na Slupi Theatre. He played football competitively for the junior teams of Sparta and Židenice.[1] Already before WWII he worked in the film industry as an assistant director. He assisted Václav Kubásek at the Hostivař studios in directing the comedy Women at the Petrol Station (Ženy u benzinu, 1939), to which he also wrote the screenplay. During the time of the Protectorate he adapted, for example, a romanetto by Jakub Arbes, The Advocate of the Poor (Advokát chuďasů). Vladimír Slavínský made one of his most successful films, Lawyer of the Poor (Advokát chudých, 1941), based on his screenplay. Together with Karel Steklý and Karel Hašler, Mach wrote the screenplay for The Town in the Palm of His Hand (Městečko na dlani, 1942)[2], based on the popular novel by Jan Drda.

After the liberation of Czechoslovakia and the nationalization of film production, many filmmakers were able to return to making films. Among them was Václav Kubásek. He offered Mach creative guidance and made him his co-director. In 1946, they produced a comedy filled with confusion, The Big Case (Velký případ), set in a small Czech town just before the end of the war. Here, the local miller bears resemblance to a Nazi officer, which causes confusion among both the German occupiers and the Czech collaborators. Mach’s first solo directorial effort also follows in a lighter tone. Two years after the war, the satirical comedy Nobody Knows Anything (Nikdo nic neví, 1947) took the audience by surprise with its lighter take on the occupation.

Courageously unserious for its time, this film follows a couple of clumsy Prague tram drivers as they try to dispose of the body of a supposedly dead SS man. They overcome various obstacles in the spirit of silent slapstick comedies. In the process, Mach ironically mocks both German and Czech nature, which is characterized more by opportunism rather than heroism. For a long time to come this was the last occupation comedy. In terms of tone, only some of the tragicomic films of the new wave come close. Mach’s other films, however, did not stand out noticeably from contemporary film production. On the contrary. With a few exceptions, they would blend in with what the others were filming.

After his debut, Mach shot one to two films a year. He continued to distinguish himself as a specialist in genre filmmaking. In 1948, he shot an adventure film for children, The Green Notebook (Zelená knížka), based on a novel by Václav Řezáč. It is set in an old suburban house in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. As the story unfolds, it is revealed that the homeowner is enriching himself at the expense of unemployed workers. In the same year, Mach made another children’s adventure film, On the Right Track (Na dobré stopě), about a group of boy scouts who beat a band of German saboteurs. Although children’s content had been on the production teams‘ agendas since before 1948, it was Josef Mach who laid the foundations of Czech children’s film with these two pictures.

Mach also made two films in 1949. The Family Problems of Clerk Tříška (Rodinné trampoty oficiála Tříšky) is a comic story of a retired housing office clerk who spends his holidays with his large family in the border region. The main character is played by Saša Rašilov, who was awarded a national prize for his depiction of the good-natured official. This optimistic comedy was a reaction to the housing situation at the time. While the industrial centers, to where workers from surrounding areas gathered, were overcrowded after the war, the periphery of the Republic was empty. Therefore, there was an effort to encourage seniors to leave the big cities to live out their lives in the countryside.

„It is probably best to say from the very start that Mach’s new comedy is not a piece of high artistic quality. It is first and foremost fun. A funny piece with taste and moderation so that it fulfils a purpose more necessary in today’s circumstances than any other – and that is to entertain in an acceptable way and to make people laugh as much as possible,“ said a contemporary review.[3] In a similar spirit – appreciating craftsmanship rather than artistic qualities – were also the reviews of Mach’s other films. But as the 1960s drew closer and the audience’s tastes changed, these superlatives would gradually dwindle. For example, his second film from 1949, the comedy The Village Revolt (Vzbouření na vsi), would hardly receive as enthusiastic a response a decade later as it did when it premiered.

The rural comedy, for which Mach received a national award, marked the director’s return to the work of Václav Řezáč. The women of the village of Čirá want to build a municipal laundry. However, they encounter resistance from the men. Through a humorous clash of the sexes, the film illustrated why small-scale farming needed to be replaced by cooperative farming and why some manual activities needed to be mechanized. So, on a second level, it was again an agitprop promoting the government’s agenda to adapt the audience to the ongoing social and technological changes.

In 1950, Mach produced the comedy Mr. Racek Is Late (Racek má zpoždění), the theme and script of which were co-written by Karel Feix, Ivan Osvald and Oldřich Lipský. The hero of the film is a baker, Mr. Racek, who gets a temporary job in a coal mine, where he reevaluates his opinion of the miners‘ work. The intention was again not only to entertain the audience, as the reviews said, but also to emphasize why coal work brigades were necessary. A year later, Mach delved into the waters of the adventure genre with the same pioneering zeal. Operation B (Akce B, 1951), based on a screenplay by Eduard Fiker, tells the story of the heroic struggle of members of the Czechoslovak army and the national police (SNB) against the “Banderites” in 1947.

The celebration of the Communist Party’s role in protecting the homeland earned Mach an even higher award, the State Award of the Second Degree. Consideration was apparently also given to the difficult outdoor filming in the Slovakian mountains, conducted in cooperation with the Ministry of National Defense and the Ministry of National Security. Operation B today is notable for its schematism and static character. But in its time, it was screened at the Karlovy Vary IFF and praised for its freshness, high level of suspense and ability to portray contemporary issues in an audience-friendly way.

The folklore musical Our Native Land (Rodná zem, 1953), which tells the story of the birth of a folk-art ensemble, was also created mainly in Slovakia. This joyous, colorful celebration of the Slovak people’s creativity follows a few boys and girls who were discovered in different corners of Slovakia and who now come together to sing, dance and laugh in an artistic collective. The aim was to capture the fusion of different generational approaches, traditions and modernity, or to display „the plethora of songs, dances and customs with which the Slovak people celebrate their lives and from which Slovak national culture draws, so richly forming in the new conditions of Slovakia’s turbulent economic and industrial development.“[4]

After the challenging production of Our Native Land, Josef Mach’s directorial career experienced a prolonged break. His next film, Playing with the Devil (Hrátky s čertem, 1956), premiered in 1957. This Christmas classic was based on the play of the same name by Jan Drda, which had already been successfully performed since 1945. This colorful fairy-tale comedy depicts a retired soldier’s battle with all of hell. A decade after his debut, Mach decided to experiment here again and preserve the theatricality of the original. The distinct artistic style of the film was determined by Josef Lada’s drawings. In addition to the setting, the actors‘ performances were also stylized. All this puts Playing with the Devil at the crossroads of theatre, feature film and animation.

In the same year that Playing with the Devil premiered, Mach produced the comedy The Bus Leaves at 1.30 (Florenc 13.30, 1957). This film describes the events that took place during a long-distance bus ride on the route between Prague and Karlovy Vary. Sitting behind the wheel is a laughing Josef Bek. The passengers represent a cross-section of Czech society heading for a better future. In order to reach their destination, they must suppress their selfish private interests and conform to the greater whole. Mach was expected to make a new type of modern comedy. But according to the critics, however, only the props were new, otherwise the film used the same familiar schemes.

Based on subject matter by Jan Procházka, who at the same time made his debut as a screenwriter, Mach produced a drama set in a contemporary village, Bitter Love (Hořká láska, 1958). The plot featuring a stubborn farmer and his two sons was criticized for being unconvincing and for the corny motifs it used.[5] Nevertheless, Mach continued his collaboration with Procházka and made a comedy from a military environment, The Missing Cannon (Zatoulané dělo, 1958). The criticisms were similar. Procházka allegedly drew from hackneyed situations and did not show much knowledge of the environment he chose to portray.

The critics agreed that „The Missing Cannon [is] a step backwards […], a return to the old trite comedy, to hackneyed jokes and figuration.“[6] According to some, Josef Mach’s entire career as a director developed in an unfortunate direction: „Bitter love only confirmed that Josef Mach is increasingly lowering the standards for his own work. Despite all the shortcomings of the script, he is partly to blame for the fact that the only rural film of last year was a loss. The situation wasn’t much better with The Missing Cannon either.“[7]

Despite the negative critical responses, Mach continued to receive lucrative assignments. In 1959, he went to Koliba to collaborate on the first Slovak feature-length fairy tale, The Nobleman and the Astronomer (Pán a hvezdár, 1959) by Dušan Kodaje. A year later, he started shooting a wide-screen color film about the Second National Spartakiad, Waltz for a Million (Valčík pro milión, 1961), again scripted and written by Jan Procházka. The musical drama depicts the story of the trumpeter Franta, who comes to the Spartakiad with the student orchestra of an agricultural school. In the Czech capital he meets a gymnast named Jana. Their acquaintance is interspersed with spectacular shots of Spartakiad performances.

The reviews, like those of the previous two films, praised Mach’s directorial skill, but were very critical of Procházka’s unconvincing script.

Young viewers in particular, however, flocked to see this romance set in jubilant Prague. So Mach had no reason to leave the light-hearted comedy genre. His next film, Florián (1960), was an adaptation of the grotesque Jírovec and His Saint Patron (Jírovec a jeho patron) by K. M. Čapek-Choda. The film, which mocks selfishness and greed, combines a fairytale motif with a realistic depiction of smalltown Czech life. Similarly, the comedy Please Do Not Disturb (Prosím, nebudit!, 1963) tells the story of a girl who makes her everyday life more interesting using fantastic dreams.

The comedy Three Men in a Cottage (Tři chlapi v chalupě) premiered at Christmas 1963. Jaroslav Dietl wrote the story and screenplay based on his series of the same name. It’s about three family generations living in the village of Ouplavice. Overall, however, Mach, like other formerly active directors, found himself outside the main interest of domestic dramaturgy and criticism during the 1960s. Also, due to the smaller workload in his homeland, he was able to accept the offer of Hans Mahlich from the DEFA film studio in Berlin. The director, perceived also abroad as an experienced filmmaker, thus became the founder of the „red“ East German westerns (so-called Indianerfilme), which were supposed to serve as a counterbalance to the West German adaptations of Karl May.

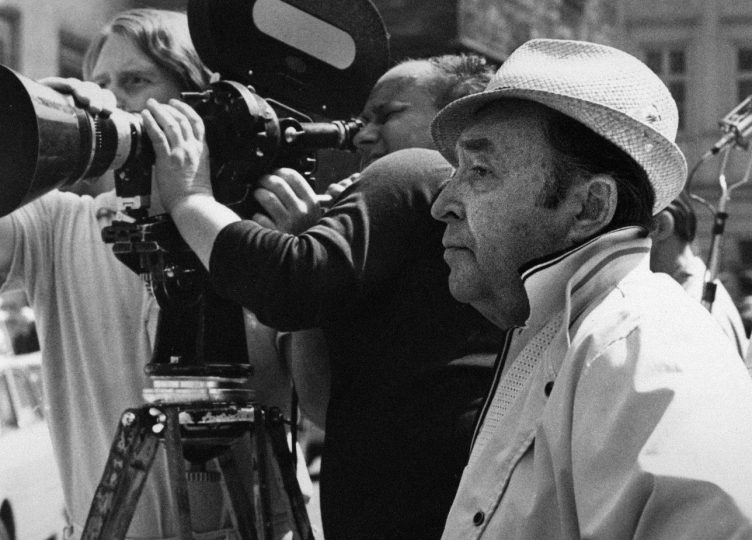

Mach made one of the studio’s most commercially successful films – The Sons of Great Bear. The story about the struggle of North American indigenous tribes with colonizers was based on the novel by Liselotte Weiskopf-Heinrich. Filming took place in Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria in addition to Babelsberg Studios. Gojko Mitić was cast in the lead role, which was his first major acting part. Although Mach took credit for discovering him, which allegedly took place on the streets of Belgrade, Mitić had already appeared in Winnetou (1963). In 1966 in East Germany, Mach was still directing Black Panthers (Schwarze Panther) set in a circus environment.

Josef Mach returned to his homeland in 1967, when he filmed The Detour (Objížďka), another small-town comedy, based on his own story and script. In the film, the life of a small town is turned upside down after a detour from the main road is channeled straight through it. As with Macha’s other comedies, the star cast, namely Jiří Sovák in the lead role and Jana Hlaváčová or Josef Bek in supporting roles, guaranteed the audience’s interest.

As Juráček predicted, Mach’s transition to the post-1968 structures of state cinematography was a smooth one. While some filmmakers were expelled from the Barrandov Studios after employee background checks, Mach, who had been in the shadows in the 1960s in Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, regained the limelight, as did Oldřich Lipský, Jiří Sequens and Otakar Vávra. He remained faithful to his undemanding genre work. However, he also tried a new genre different than comedies or adventure films. Based on the book Series C-L (Série C-L) by Eduard Fiker, he produced the detective film The Murderer Waits on the Rails (Na kolejích čeká vrah, 1970).

Mach’s most significant contribution to the consolidation process was the film Man Is Not Alone (Člověk není sám, 1971), in which Jiřina Švorcová, with the help of the always helpful Czechoslovak secret police, tries to clear the name of a scientist suspected of abetting saboteurs. Mach returned to the comedy genre with The Three Innocent (Tři nevinní, 1973), writing the main triple role for his favorite actor Jiří Sovák (they made a total of nine films together). On 3rd May 1974, Josef Mach was awarded the title of Meritorious Artist for his lifelong (pro-regime) work. Oldřich Lipský and Vladimír Menšík received the same award from the Minister of Culture.

Until his death in 1987, Josef Mach produced only two more films, a biography of the painter Josef Mánes, Palette of Love (Paleta lásky, 1976), and a spy film from the pre-February 1948 period, The Quiet American in Prague (Tichý Američan v Praze, 1977). In the latter, a group of American intelligence agents plot a government coup in Czechoslovakia. They want to take over positions in the government and the army using their people. This naive, rightfully forgotten spy story concluded the filmography of a director, who one critic in 1949 had described as someone that made „good average movies,“[8] which had been true for three decades.

Mach’s works generally did not impress in terms of formal design. He did not choose ambitious, provocative, out-of-the-box subjects. He was a people’s director in the best sense of the word, because he was able to identify which themes were pressing and current for society, and then he processed them in a way that guaranteed – often thanks to the use of comedy genre – entertainment.

Literature:

Daleká cesta k Missouri. Kino 21, 1966, no. 1 (13th January), p. 2.

Miloš Fiala, Prosím, nebudit! Kino 18, 1963, no. 14 (4th July), p. 11.

Jiří Hrbas, Josef Mach. Film a doba 22, 1976, no. 1, pp. 6–19.

Štěpán Hulík, Kinematografie zapomnění. Prague: Academia 2011.

JJ, Za režisérem Josefem Machem. Záběr: časopis filmového diváka 20, 1987, no. 12 (28th July), p. 2.

Aleš Merenus, Výborné divadlo jako hezký film aneb Archeologie filmových Hrátek s Čertem. Iluminace 28, 2016, č. 2, pp. 77–103.

Jan Pilát, Valčík pre milión, film pre 4 milióny. Film a divadlo 4, 1960, no. 18 (30th September), p. 5.

Posledný z generácie. Film a divadlo 31, 1987, no. 21 (28th September), p. 8.

Pavel Skopal (ed.), Filmová kultura severního trojúhelníku. Brno: Host 2014.

Pavel Skopal (ed.), Naplánovaná kinematografie. Prague: Academia 2012.

Notes:

[1] Later on, Mach will live his love for sport during regular football tennis tournaments of Barrandov staff.

[2] This was the last film on which Karel Hašler collaborated. Shortly before finishing the exterior scenes, he was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo based on a denunciation.

[3] ŽLM, Rodinné trampoty oficiála Třísky. Kino 5, 1950, no. 2 (19th January), p. 34.

[4] K dokončení filmu Rodná zem. Filmové informace 4, 1953, no. 49 (10th December), p. 12.

[5] The film did not have a great reputation even at the Barrandov Studios. Based on the memories of dramaturge Marcela Pittermanová, the script was called „kulak in plaster“. Štěpán Hulík, Kinematografie zapomnění. Prague: Academia 2011, p. 134.

[6] Jaroslav Boček, Na okra našich nových filmů. Kultura 3, 1959, no. 16 (23rd April), p. 5.

[7] A. J. Liehm, Poznámky k bilanci. Film a doba 5, 1959, no. 4, p. 238.

[8] Jaroslav Dvořáček, Zelená knížka. Kino 4, 1949, no. 13 (23rd June), p. 188.