One of the indicators of how advanced a society is can be its approach to its most vulnerable members and how it treats its national, religious or ethnic minorities, as well as people with various kinds of disadvantaged backgrounds. This applies both to behaviour in real life and to how they are depicted in the media, as both are closely connected. The media’s importance increases precisely when we lack direct personal experience with a particular social group. According to media theorists and sociologists, in such cases we are more likely to accept what the media present to us as reality (and what is usually a reflection of the prevailing stereotypes and predominant values). A very broad and sensitive area is the depiction of mental illness.

Since the expansion of mass media, people have been informed about issues tied to mental illness by the daily press. A more profound insight into living with mental illness has been provided by fiction. And over the last 120 years or so, the awareness that some people are somewhat different has also been significantly shaped by the cinema. Films give voice to deep-rooted, time-conditioned representations of a particular group of people, including their characteristic behaviours and appearance, allowing us to put ourselves in the position of a person who thinks and acts differently. From their earliest childhood years, audio-visual works can foster greater empathy with viewers, but they can equally generate false and stigmatising ideas about how mentally ill people will act in the real world.

A well-known example of the media’s extraordinary influence on public awareness of mental illness is the American melodrama Rain Man (1988), which in many ways gives a highly simplistic representation of the autism spectrum disorder. Nonetheless, many people still base their perceptions of people with autism on this Oscar-winning film starring Dustin Hoffman. The lack of media literacy means that audiences don’t sufficiently consider how distorting media representations are by definition, especially the fictional ones. Much is omitted, and some things are highlighted for dramatic effect at the expense of other characteristic features. It is always a matter of choice and conversion into the code of the given medium.

The American sociologist Erving Goffman understood stigma as a phenomenon in which some people are marginalised from society by the so-called normal majority due to a certain characteristic that distinguishes them from others. While society can usually „handle“ cancer or other bodily ailments, a mental illness is not visible and is more difficult to accept. Rather, more often than not, people suffering from mental illness are framed as undesirable or dangerous – their social standing is devalued. In the Czech Republic for instance, a March 2020 survey by the Public Opinion Research Centre showed that 59% of the interviewed Czechs would not want a mentally ill person as their neighbour.

Although this represents a slight improvement compared to previous years, the results of the survey still indicate a relatively high level of stigmatisation towards people with mental illness, and consequently a small willingness to include these people in their lives. One reason for this may be the selectiveness of the media. Serious illnesses such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, which lead to a distorted perception of reality, receive more media attention than the following more widespread conditions – depression, panic disorder or anxiety. Moreover, we often hear about people with a psychiatric condition in connection with committed criminal offences, where a link between the act and the illness is automatically assumed. This fosters the common myth that people suffering from mental illness are dangerous.

Social exclusion is thereby added to the diagnosis itself. It is not uncommon for patients to adopt this negative thinking about their own health, and as a result they bear a double burden. Given that, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, mental illness affects around 30% of the Czech population, this is not a marginal issue.

According to Cultivation Theory, our perceptions of the world can change following long-term exposure to the media. When certain information and perspectives are presented over a long period of time, it creates a specific framework and leads to the internalization of patterns related to the phenomenon. In the same way, watching a character with whom one can identify, can have a positive effect on one’s own self-esteem. People feel more represented and valued as full members of society. However, insufficient or inaccurate representation can have the opposite effect. When someone rarely sees people like themselves in the media, they may feel insignificant and unaccepted. Movies have the unique ability to not only capture, but also articulate and support what matters to society.

The social-constructivist perspective, which believes that reality is a constantly transforming social construct, prompts the question of how the Czech media, in this case specifically feature films, contribute to this construct. What types of characters with mental illness can be identified in the Czech cinema? What is their place in the narrative?

The first pictures from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, not only the Czech ones, are an echo of the times when people with disabilities were confined to institutions, excluded from society and hidden from the public eye, or faced pressure not to show their handicap. They were simply not granted the same rights as the rest of society. In movies of the silent era, we find a number of mad scientists and lunatics whose actions cannot be logically explained (a parody of this popular character type is Orfanik played by Rudolf Hrušínský in The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle, [Tajemství hradu v Karpatech] 1981). We cannot accurately diagnose these archetypal figures, whose appearance dates back far into the past. They represent irrationality as such and are consistent with the period discourse in which mental illness represented something mysterious for which medicine had no explanation. Like authors before them, filmmakers realized (for the implied reasons) that these characters were ideal for the horror and detective genre. The association of variously deranged characters with these genres, however, continues to the present day.

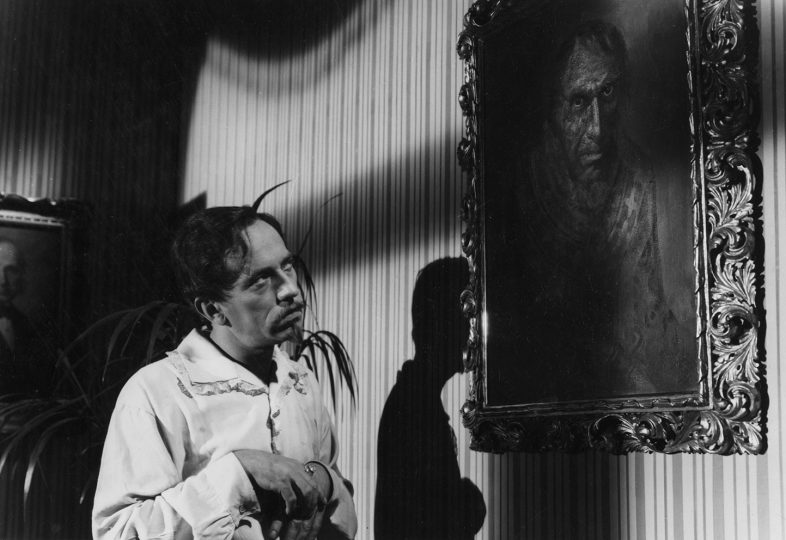

In horror movies, the threat that mental illness poses to society and its stability is dramatized through deranged characters. Behaviour that defies the realm of rationality serves primarily as a tool for evoking terror and unease, as a metaphor for what cannot be integrated into the known structures of knowledge. This can be seen in the domestic example The Portrait (Podobizna, 1947), based on a short story by Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol. At the centre of the story is a painting, which causes the characters to descend into madness one by one. Death is their only escape. The archetype of the dangerous madman is also used in The Curse of the Hajns’ House (Prokletí domu Hajnů, 1988), an adaptation of Jaroslav Havlíček’s book. Petr Čepek plays the character Cyril, who is convinced he is invisible. When he tries to rape his niece Sonia, the young woman also goes mad because of the trauma. In both films, madness is transmitted from character to character like a contagious disease.

Mentally ill people are also a threat in later horror films such as An Eye in the Wall (Oko ve zdi, 2009), based on a short story by Iva Hercíková, or T.M.A. (2009) by Juraj Herz. The film Normal (2009) also explores the conventions of (expressionist) horror, where Milan Kňažko plays a character inspired by the sadistic serial killer Peter Kurten. Mental disorder – traditionally a hereditary form of insanity – is also ultimately confirmed in the case of the antagonist in Zdeněk Troška’s romantic historical drama Angelic Face (Andělská tvář, 2002). The representation of mental illness in these films is subject to genre conventions, and we can assume that the audience accepts them accordingly – i.e. not as realistic images.

The physical and psychological breakdown of the individual is depicted with greater authenticity in the horror-themed Oil Lamps (Petrolejové lampy, 1971), another Havlíček adaptation starring Petr Čepek. This time the reason is not inherited madness, but syphilis. However, also in this case the character’s deterioration is expressed, among other things, by the fact that he tries to rape a woman, namely a young maid. In contrast, the protagonist of The Cremator (Spalovač mrtvol, 1968) is a psychopath from the very beginning of the narrative. The worst aspects of his personality, however, only begin to emerge after the rise of Nazism, when he acquires ideological support for his sick visions. Morgiana (1972), which was originally intended to be a much more overt account of schizophrenia, also has a sinister edge. All three films are connected by the personality of director Juraj Herz, who was fascinated by the dark aspects of the human nature throughout his career.

In detective stories, madness usually serves as a trigger for suspicion – the different behaviour is out of place, something about it doesn’t add up. Therefore, it needs to be subject to an investigation based on logical reasoning and the order that had been disturbed by the irrationality must be restored. The boom in detective stories featuring characters with various mental and experiential disorders took place in Czechoslovakia hand in hand with the expansion of psychiatric care in the 1960s. The popularity of this genre, which is now more frequent on television screens, continued into the 1980s. Mental retardation, aggression, paranoia, hallucinations, sadism, and other types of paraphilia… See, for example, Death of Hitch-Hikers (Smrt stopařek, 1979) or Petr Schulhoff’s four dark psychological detective stories with Rudolf Hrušínský as Major Kalaš: Fear (Strach, 1963), The Murderer Hides His Face (Vrah skrývá tvář, 1966), On the Trail of Blood (Po stopách krve, 1969), Diagnosis of Death (Diagnóza smrti, 1979). The mentally ill characters are not always also killers or rapists, but the genre framework itself gives them an unsettling quality.

The less known crime drama The House of Lost Souls (Dům ztracených duší, 1967) revolves around a psychiatric hospital nearby which the body of one of its patients is found. Various institutions are still a common way in films to indicate that characters have mental problems, may be potentially dangerous to themselves or others, and should be medically treated under expert supervision. Sometimes this is taken in all seriousness (Dead Bug, [Mrtvej brouk] 1998), other times it can be a parody, whether intentional (The Girl on the Broom [Dívka na koštěti,1972], Joachim, Put Him into the Machine [Jáchyme, hoď ho do stroje, 1974]) or unintentional (Daria, 2020).

However, some titles, such as the so-called vault film The Ark of Fools or Tales from the End of Life (Archa bláznů, aneb Vyprávění z konce života, 1970), relativise the distinction between normal and insane characters and blur the boundaries between the two worlds. In Ivan Baladi’s only completed film, the head of a mental institution attempts to transform this neglected facility. But he cannot help the patients. On the contrary, his attempts at reform give rise to suspicions that he himself is ill. Similarly, Jan Švankmajer’s Lunacy (Šílení, 2005) can also be perceived as an allegory of a repressive society that is unable to incorporate absolute freedom into its structures. The growing anxiety and volatility of Nadia, the protagonist of Unbalanced (Zešílet, 2022), is also a reflection of a distorted external world with disrupted social structures.

The black and white ballad-like film Vojtěch, Called Orphan (Vojtěch, řečený sirotek, 1989) by Zdeněk Tyc is more a story of defiance against the prevailing order than a realistic portrait of a man with a lower intellect. The main character lives outside the system, in harmony with nature. Nevertheless, he longs for socialisation, or at least contact with women, which is „traditionally“ manifested by his attempt to rape a young student (who later becomes his partner). Tyc expanded his debut in terms of motive – and also by using multiple metaphorical images – with the autobiographical film Razor Blades (Žiletky, 1993), whose misguided protagonist searches for serenity in a psychiatric clinic.

Requiem for a Maiden (Requiem pro panenku, 1991), Filip Renč’s naturalistic directorial debut, is also open to metaphoric interpretation. The underage main heroine finds herself in an institution for the mentally ill due to a bureaucratic error. She subsequently faces sadistic and drastic disciplinary methods from one of the orderlies. Although this treatment of the inmates was actually inspired by real events at the Institute of Social Services for Youth in Měděnec in the Ore Mountains, they can be metaphorically interpreted as a testimony of the cruelty of a totalitarian regime that deprived citizens of their autonomy and dignity. Although the exploitative film exaggerates negative events, it has become embedded in the public consciousness and for a long time has been used to justify why large institutions for people with disabilities should be reformed. The high concentration of people in psychiatric facilities is consistent with the real state of the Czech mental health care before 1989.

Evald Schorm approached the subject of institutional care and the associated stigma with greater sensitivity in his psychological drama The Return of the Prodigal Son (Návrat ztraceného syna, 1966), where engineer Jan Šebek attempts suicide. His stay in a psychiatric institution, however, does not alleviate his feelings of existential anxiety, uprootedness and insecurity. The impulse to produce this film was the high suicide rate in Czechoslovakia at the time, as well as a greater willingness to address the issue publicly (for example, the Healthcare Act No. 20/1966 Coll. was passed a year before the film’s premiere). Schorm critically examines Jan’s diagnosis as being „crazy“. The protagonist became less free, paradoxically, because he dared to express his individual freedom. Others watch him intently after his suicide attempt, believing they have the right to control his life.

Schorm’s film, which is equally psychological and socio-critical, also stands out in that it sees depression as society’s problem, a reaction to a difficult situation, not as an individual’s weakness, as was often the case in neoliberal discourse. The overall depiction of depression and anxiety in Czech cinema is, however, relatively rare, which may be related to the low prominence (and thus difficulty in visualising) of the causes and manifestations of mental pain. In the Normalization dramas Lovers in the Year One (Milenci v roce jedna, 1973) and Leave me alone! (Nechci nic slyšet, 1978), severe trauma is the reason for the characters‘ reclusiveness and paralyzing sadness (rape by German soldiers in the first film, the death of parents in a car accident in the second). Meanwhile, the young heroine of Lea (1996) has not spoken since she witnessed the brutal murder of her mother. The single mother Dáša from Something Like Happiness (Štěstí, 2005), who is struggling to raise her two boys, manifests her mental illness in hysterical scenes and promiscuity. Unable to exercise self-control, she ends up in hospital.

Some films from the last two decades have nevertheless avoided such a strong initial impulse, or even an affective, even theatrical expression of inner unease, indicating the growing awareness of mental health issues among some filmmakers. The emotionally dampened Parallel Worlds (Paralelní světy, 2001) owe their persuasiveness to the performance of Lenka Vlasáková, whose character Tereza falls into an increasingly deeper depression mainly because of her insecurity and fear of separation, not childhood or teenage trauma. The unhappy protagonist of Moments (Chvilky, 2018) cannot seem to find the words to describe her problems during a therapist session. The psychologist Eliška struggles with psychosomatic issues in the emotional Two Ships (Marťanské lodě, 2021), becoming increasingly self-absorbed and harder to understand for her partner and the audience.

While the three mentioned films evoke sympathy for their tormented heroines, Jan Těšitel’s David (2015) presents us with a more difficult challenge. The protagonist, a young man with an intellectual handicap, perhaps an autism spectrum disorder, is not a likeable character; he does not evoke pity. He runs away from home, masturbates in the train station toilet, shoplifts, suffers an uncontrollable seizure… The filmmakers do not moderate the symptoms of his illness to make him more appealing and easier to process. To spend most of the film in David’s proximity is not a pleasant experience. If we want to connect and have empathy with him, we must step out of our comfort zone, also in light of the minimalist, non-communicative narrative. This raw, dark film was a revelation also because cute, amusing or daydreamy „fools“ are much more common in Czech cinema.

Apart from characters who pose a threat and arouse fear, there has been a comparatively long „tradition“ of infantilising people suffering from mental illnesses in Czech cinema. Their prototype could be the Idiot from Xeenemünde (Blbec z Xeenemünde, 1962), from Jaroslav Balík’s medium-length satire, who in wartime Germany begins to kill his fellow countrymen with home-made rockets, or Otík from My Sweet Little Village (Vesničko má středisková, 1985). The grown man with the intellect of a child amuses the audience and the other characters in Menzel’s tragicomedy with his appearance alone (with headphones on his protruding ears and a broad smile). At the same time, his character makes the humanity of the other villagers stand out, which is his main function in the narrative. Eventually, even the strict driver of the cooperative truck, Pávek, takes pity on the troubled racer and brings him from Prague back to the countryside, where he feels safest. Otík himself does not experience any development.

This type of protagonist with mental illness is used in many other films (and not just Czech ones) to reinforce the characterisation of someone else and to make the audience feel deeply moved. Fanny (Fany, 1995) tells the story of two adult sisters, Jiřina and Františka. The latter is mildly mentally challenged. Following her mother’s death, her aunt takes care of her. But she decides to move to America to be with her son. The sister is therefore reluctantly taken in by Jiřina. She doesn’t want to send her to an institution because she promised her mother before she died that she would take care of Fany. A disabled person is initially a burden, a curse to their loved ones, although not as literally as in The Curse of the Hajns’ House. Fany acts like a child – and is treated as such by others. But she threatens no one but herself. On the contrary, she triggers the humanisation of Jiřina by her guilelessness and reliance on others. After fulfilling this task, she dies.

Václav (2007), the protagonist of Jiří Vejdělek’s tragicomedy of the same name, has a less tragic fate. Václav is a man in his forties with an undefined mental impairment, whose disability changes depending on the needs of the script (e.g. suggesting an inability to distinguish delusions from reality). His actions constantly cause problems in the village where he lives (firing a gun at the postman, painting the office of the chairman of the agricultural cooperative). His family must continuously smooth things over for him. However, they do not become more sensitive through these interactions. Their patience gradually wears thin. The protagonist’s misdeeds become more and more serious until they escalate and Václav fires a gun at his brother, who had brutally beat him. He ends up in prison, but after four months is granted a presidential pardon. The crucial point is thus the presentation of the man with mental illness as a burden to the family, whose members don’t seem much more „normal“ than him, and at the same time we witness someone with whom one can only sympathize.

A more clearly outlined character, though again used mainly to mirror how abnormally others behave, is František from The Idiot Returns (Návrat idiota, 1999). After his release from rehab, he starts integrating back into society, as an immaculate pure soul trying to help others and to not cause harm to anyone. However, his guilelessness and lack of prejudice backfire on him several times. The otherness that František embodies in the film provokes hostile reactions and vigilance. What distinguishes Bored in Brno (Nuda v Brně, 2003) from other dark comedy films about village fools and harmless city idiots (see also Young Girls, Crazy Guys [Blázni a děvčátka, 1989] or Shark in the Head [Žralok v hlavě, 2004]) is that it does not approach mentally ill characters as children or saints. Instead, it addresses with their sexuality.

Standa and Olinka are two young people with intellectual impairments and are in love and about to have their first physical contact after a year-long pen-pal relationship. Although Standa enjoys fairy tales, to which the film also refers visually, he is also interested in women and is clear about wanting to have sex with Olinka. Thereby he is not presented merely as an overgrown child and observer of other people’s relationships who does not have drama of his own. He must overcome obstacles himself to get close to someone, which he eventually does. It even seems – in what can be perceived as a certain idealisation – that his relationship with Olinka is of more intense and more loving than those of „healthy“ people.

Although many stereotypes continue to persist over time, the focus on negative aspects such as violent tendencies is slightly less frequent in depictions of mental health in works after 1989. In the wake of projects fighting prejudice and the reform of psychiatric care, there has been a rise in plots attempting to normalise mental health issues, where these characters are not locked up in institutions but integrated into society (which of course brings with it another set of concerns for their families and caregivers).

Perhaps also thanks to the reform of the psychiatric care system and the ensuing efforts to demystify and destigmatize psychological illnesses, we see an increase in films that do not rely on the „familiar“ type of madman or madwoman, but in recent years movies work with a more clearly defined diagnosis, albeit with certain limits. In the drama Together (Spolu, 2022), Štěpán Kozub plays a man with autism. His character Michal seems at times like a child, at times like a high-functioning autistic person whose autistic traits are emphasized dramatically. Occasionally, though, he exhibits unexpected empathy or says insightful lines and shows self-reflection. Moreover, at the end of a film based on a number of autism myths comes the absurd revelation that the character’s mental disorder was brought on by an accident.

Martha Issová also plays an autistic character in the film Buko (2022). The simplifications and clichés that Czech filmmakers usually resort to when depicting the autism spectrum disorder are perhaps not so obvious here, thanks to the collaboration with a child psychiatrist. Compared to foreign works, however, we still see a prevalence of reducing characters that are different (which, in addition, is their main defining feature) primarily to a source of inspiration and humorous situations. Furthermore, the fact that Tereza is specifically autistic is lacking a deeper justification in the script.

As can be seen from our brief outline, in Czech cinema we can identify several recurring types when it comes to the representation of mental illness (dangerous maniacs who are feared by others vs. harmless fools who evoke amusement and sympathy), but also a wide range of characters who cannot be easily labelled in this way. Often, however, they are more likely to be passive objects of pity, or saviours and sources of inspiration to others whose own past, needs, and feelings are not given as much attention, or they are universally unhappy characters, suffering, and ultimately dying tragically. In the first case, the characters are there to help the „normal“ world; in the second case, the world must help them. In both instances, they are reduced to one aspect of their identity – their handicap. The question is whether the predominance of this pattern suggests that even as a society, we expect these people to be merely secondary, supporting figures in the story of someone we would call „normal“.