In totalitarian regimes, allegories or other methods of indirect expression have represented one of the few ways for filmmakers to critique contemporary society or the establishment itself in their films. The establishment was naturally aware of this, and both sides thus tried to advance their own interests using various methods. After the period of normalisation, the second half of the 1980s brought a loosening that – in Czechoslovak film – was characterised by more civil and sometimes even documentary-style films with socially-critical topics such as Why? (Proč?, 1987) by Karel Smyczek and Bony and Peace (Bony a Klid, 1987) by Vít Olmer, and that eventually culminated in the demise of the socialist republic at the end of the decade. To portray reality, it was no longer necessary to use complicated symbols; the dictatorship of ideology and state was replaced by the dictatorship of money, and some films were produced faster in more modest production environments and were designed to attract viewers’ attention in the most effective way. Their style is characterised by attempts to be straightforward and direct, and usage of attractive themes and tabloid methods[1]; more layers were sacrificed in favour of attacks on the primary instincts of the viewers. As distorted as this superficial reflection may be[2], these commercial spectacles conserve the reflection of their time much better than timeless artistic films.

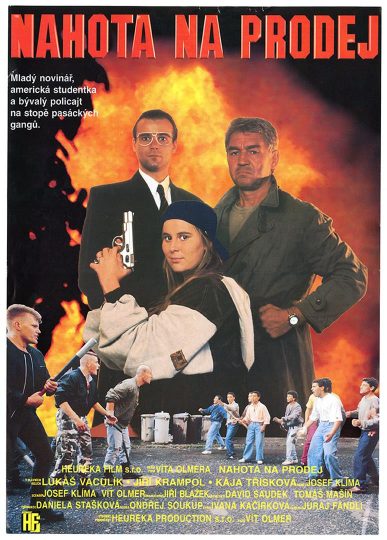

It is for this specific quality that the aforementioned films could become sought-after goods in the future – if they are not being already rediscovered today. An exemplary case of this process is arguably the whole post-revolution filmography of director Vít Olmer and in particular his Nudity for Sale (Nahota na prodej, 1993) provoking ambivalent reactions from shock and shaking one’s head through amusement all the way to a certain kind of admiration. When it premiered, the film received scathing reviews, but it was a box office hit, and with 865,367[3] viewers, also the film had the third-biggest attendance of the year in Czech cinemas.[4]

To this day, the average rating on various online Czech film databases is negative, but when looking at individual ratings, we find out they are often either the lowest or highest possible, and some commentaries label Nudity for Sale as “a phenomenal memento of its time and age.” As some users mention, the film was brought back to the spotlight thanks to an article in Premiere magazine from 2008 with an introduction stating that “every mature film industry needs its hilariously bad films” [5] saying that the viewers will have a good time as long as they don’t take the film seriously. But that doesn’t change the fact that the authors of Nudity for Sale meant their film seriously, and the record number of cinemagoers probably didn’t visit the cinemas to be amused in the first place. So, what can the film say about itself by its choice of themes, method of storytelling and the construction of its characters, provided that we don’t think of it as of a bizarre relic of a time of weird taste?

The West is Just an Inch Away

“Their descent into the underworld is lined by various crimes, from frauds through corruption all the way to the climactic bloodbath, as if taken from Hollywood films. (…) The intention is clear: to serve the viewers an “American” film set in the Czech Republic,” [6] writes Filmový přehled about Nudity for Sale. The framework for watching and perceiving the film is provided, and let us add that it had its grounds. Nudity for Sale was one of the first projects of Heureka Film, a company that bought expensive special effects equipment and was determined to compete against American genre production.[7] Vít Olmer, who later stated that if he had a choice, he would have focused on other projects, was at the time inclined to making American-style action films. Two years prior to that, he turned down an offer to direct The Elementary School (Obecná škola, 1991) written by Zdeněk Svěrák because he wanted to adapt something less tame but rather rawer and more topical. [8] After the very successful Tank Battalion (Tankový prapor, 1991), Olmer found what he was looking for in a story about prostitution and pandering by investigative journalist Josef Klíma. Together, they wrote a completely fictitious script about a journalist named Egon who descends into the Czech underworld dreaming about getting material for an attractive news story and perhaps also rescuing an innocent girl from the grip of Romani pimps.

He is accompanied by an American student of Czech origin named Nancy who came to the Czech Republic to carry out a research project about local journalism as at American universities “no one really knows if it’s freedom or they write about the same old shit”, and a retired cop named Joe, referred to throughout the film and in the credits only as “Cop”. Alluding to its American counterparts, the three different characters try to find a way to each other and gradually untangle the network of a mob organisation that emerged during the “resurrection” of our country right after the Velvet Revolution in 1989. The country still finds itself in a strange period of development as the “old” isn’t gone (the constant shortage of everything is reminded at the very beginning of the film by the broken starter of Egon’s car) but the “new” is ready to stake its claim – as if the Czech Republic, previously long tied to the Soviet Union, was reaching its hands to the West.

This fermentation serving as a background to the plot is probably what fascinates today’s viewers and represents the zeitgeist time capsule. An influx of everything the free market has to offer (and what socialism barred from entering) from modern technologies (the mob boss already owned a mobile phone[9]) to Eastern philosophies, represented by firewalking, which Egon covers in a story and tries himself. In Nudity For Sale, we can notice the roots of visual smog in public space (a frequent topic of discussions today) in the form of ubiquitous billboards, neon signs and advertisements – one of them, on Wenceslas Square, invites us to the newly opened McDonald’s restaurant, a symbol of American consumerism. But the authors’ main focus isn’t documenting Czech stereotypes in the early years after the revolution, it lies in the “tax for democracy”, as Egon’s boss puts it, in the form of a criminal case from the world of organised crime.

Or does it? We can surely agree that the starting point of the story comes when the father of a missing girl named Dita asks Egon to investigate her disappearance and thus initiates the subsequent search. But rather than a seamless flow, the plot dramaturgy serves to present the described attractive themes (exploitation approach) as phenomena that emerged after the revolution. Because of that, some scenes with two characters discussing racism, prostitution and even general topics may come across as illogical or may provide excessive information. The exemplary sequence of this type is the conversation Egon and Nancy have on the bank of Vltava. It’s not important that their confused contemplations unexpectedly changing directions find some answers, the point is that they mention several keywords: capitalists, mobsters, Prague… The way the relatively surprising point of the film is handled is also a testimony of the importance of this method. The revelation that Dita prostitutes herself willingly is quickly overshadowed by the reason she does so: she believes that her client Karl will take her with him to Germany and she will find a better future. So it’s not about Dita’s fate (that would probably be important to her father, but he only serves as a catalyst of the film’s story), but rather about all the material we gathered with Egon that can now be used in his article with a striking title Nudity for Sale.

Founding a Union of Czech-American Friendship?

Today, the interest in Nudity for Sale is the result of what the authors gave it rather unintentionally or incidentally. But, as mentioned before, it became an instant box-office hit. What were the reasons? Apart from a massive promotion campaign,[10] an important role was played by the fact that the film reached the audience at a very good time and managed to strike the right chord. The film poured everything that was previously in short supply (violence, eroticism, action) to the silver screen, associated itself with admired Western icons, and managed to sell everything as a reflection of contemporary problems. It capitalised on the moment when Czech society sobered up from the post-revolutionary euphoria and showcased the seamier sides of capitalism in full force. Along with an inclination to Western genres and its socially-critical tone, the film has one more aspect that, in fact, opposes the first mentioned tendency – an attempt to stop the flow of Western thinking and the shift of traditional values.

Nudity for Sale transfers contact with the West represented by the United States from the formal level to the thematic level by means of its protagonists. Nancy, who is their embodiment, introduces American customs and viewpoints, or at least their stereotypic notion. For her, an absolute trust in the state and its institution is crucial, so when getting to know the Czech environment, she never ceases to be amazed that there are no “social programmes” that would help ethnic groups find their place in the society, and when discussing prostitution, she suggests that “the prostitutes should have a union”. Nudity for Sale presents this attempt to transfer a way of thinking between cultures with different historical developments as a process that is unproductive and potentially dangerous, as best evidenced by the fate of one the film’s minor characters, Egon’s girlfriend Eva. Thanks to her job as a therapist, Eva quickly adopts foreign ways of thinking and, being devoted to exact procedures, now tries to apply psychoanalysis on Egon. But all her tests and graphs are pointless when confronted with the real problem – aggressive Romani pimps.

On the other hand, the practical approach (and therefore the right one) is represented by Egon and the Cop, two seasoned men and defenders of conservative values. Their parts are clearly laid out. As the brains of the operation and a journalist, Egon uses his intellect to deal with problems while the Cop, hired as a bodyguard thanks to his skills, uses brute force. The protagonists naturally have their weaknesses; Egon is an idealist whose desire to find the truth makes him jump to conclusions, and the Cop, who is tired of life, at first exhibits an unwillingness to return to action (a cliché of a detective who is forced by circumstances to go out there again). But what is important is that when the moment comes, they can pull together and are ready to act and even risk their lives. This quality is presented as their biggest strength, which gives them the right to laugh at “the achievements of the spoiled West” in their free time – for instance when Nancy tells them about her dog, who has his own toothbrush and psychiatrist. Even Nancy eventually proves to be a valuable member of the team, but she must take a gun in her hand and give up on her dreams of a union for prostitutes. From this point of view, the message of the film is clear: even in the Czech Republic, we can see a plot like from a foreign genre film, but we have to make the rules of the game ourselves, not thoughtlessly accept Western trends.

Even though the simple classification of the film’s heroes into two groups faithfully reflects the fundamental elements of their personalities, it doesn’t cover all the nuances. Among them are for example the personal lives of the protagonists, in particular the volatile relationship between Nancy and Egon (as well as the overshadowed relationship of Egon and Eva). At first, Nancy rejects his advances (“You sexist! You pig!”), but before long, she changes her mind and without any prior motivation, she succumbs. Egon then brings her breakfast in bed in the form of an apple with little American and Czech flags pinned into it, kisses her and says, “While you were sleeping, I founded the union of Czech-American friendship”. Much like the plot, the characters’ behaviour is often adjusted to conform to a concrete message that can in this case be deceiving. What seems to be an offer of friendship eventually comes across as a symbolic gesture of conquering the West and along with it its adored export, genre film.

In Retrospect

With the passage of time, it came to light how close the criticism of contemporary problems and their exploitation really is, and if we have a tendency to see the aforementioned films from before the revolution as an opposition to the totalitarian regime, i.e. socially-critical, then the films made after the revolution lost their target, and only the second thing remained. Nudity for Sale perfectly managed to exploit all the vices brough by the early 1990s as well as its model, the genre film in general. Its theme and its story are reminiscent of a genre film, but if we look past its shell, we find a hidden story layer about the change of our attitude towards the United States and their goods after the fall of the iron curtain, governed by fear of a potential cultural imperialism. In this respect, Olmer’s first “American” film in a Czech setting can in fact be interpreted as a weapon against American films in Czech settings.

This layer exploring the uncertainty of the time when Nudity for Sale was filmed has with the passage of time lost its topicality, and only that which makes it a “humorously bad film” remained. Because of the extent to which the film used it, the omnipresent sexism and racism is almost comical, but laughing at it brings a certain soothing feeling. It creates a distance between us and the material we observe as something long dead – this approach reflects labelling Nudity for Sale as a “memento” (of its time). It is easily understandable how this cliché came into existence. The concentration of the phenomena of the early 1990s in Nudity for Sale is so strong that watching it even a few years after its premiere must have felt like a journey back in time. But it would be a mistake to think that a film with similar values cannot be made today. Ten years ago, one of its “followers” was premiered, and with regards to the number of viewers, it did very well in the cinemas.

Sources:

BARTOŠEK, Tomáš, Nahota na prodej. Filmový přehled, 1993, no. 1, p. 21–22.

CÍFKA, Petr, Nahota na prodej. Premiere, 2008, n. 11, p. 74–77.

FLÍGL, Jiří, New Yorku a Libni zdaleka se vyhni. Cinepur, 2010, no. 68, p. 4–7.

HALADA, Andrej, Český film devadesátých let: od Tankového praporu ke Koljovi. Prague: Lidové noviny Publishing House, 1997.

PROKOPOVÁ, Alena, The Beginning of Capitalism in Czechoslovakia or Czech Restitution Comedy. Alenčin Blog. Available at WWW: http://alenaprokopova.blogspot.com/2011/04/zacatek-kapitalismu-v-cechach-aneb.html

SEDLÁČEK, Jaroslav, Vít Olmer. Cinema, 2002, no. 9, p. 88–91.

Notes:

[1] You can find a detailed article by Jiří Flígl on Czech exploitation films made after the revolution in Cinepur, no. 68 from 2010.

[2] Alena Prokopová, The Beginning of Capitalism in Czechoslovakia or the Czech Restitution Comedy. Alenčin Blog. Available at WWW: http://alenaprokopova.blogspot.com/2011/04/zacatek-kapitalismu-v-cechach-aneb.html

[3] Cinema attendance published at server kinomaniak.cz

[4] Only Spielberg’s Jurrasic Park (1993) and Czech film The End of Poets in Bohemia (Konec básníků v Čechách, 1993) by Dušan Klein had bigger attendances.

[5] Petr Cífka, Nahota na prodej. Premiere. 2008, no. 11, p. 74–77.

[6] Tomáš Bartošek, Nahota na prodej. Filmový přehled, 1993, no. 1, p. 21.

[7] As Vít Olmer say in an interview with Jaroslav Sedláček for the September issue of Cinema, 2002.

[8] See the second episode of the documentary series Capricious Years of Czech Film (Rozmarná léta českého filmu).

[9] A classic example of an achievement of modern times, even more accentuated two years later in Olmer’s Playgirls (1995).

[10] In his aforementioned article in Premiere, Petr Cífka mentions the signing sessions of the authors, release of the soundtrack, publishing of a literary version of the script and the film’s premiere accompanied by fireworks.