The biggest attraction of the Czechoslovak Pavillion at the 1967 Expo in Montréal was a spectacle named Kinoautomat. The system enabling the audience to vote how the interactive film titled One Man and His House (Člověk a jeho dům) should continue was created by a team led by Radúz Činčera, who was in charge mainly of the technical aspects of the project. The script of the film was written by Pavel Juráček, and live-action scenes were directed by Ján Roháč and Vladimír Svitáček. Just like the Laterna Magika, the world’s first multimedia theatre, the Kinoautomat screenings utilise the interaction between an actor – moderator (Miroslav Horníček), filmed scenes and the audience.

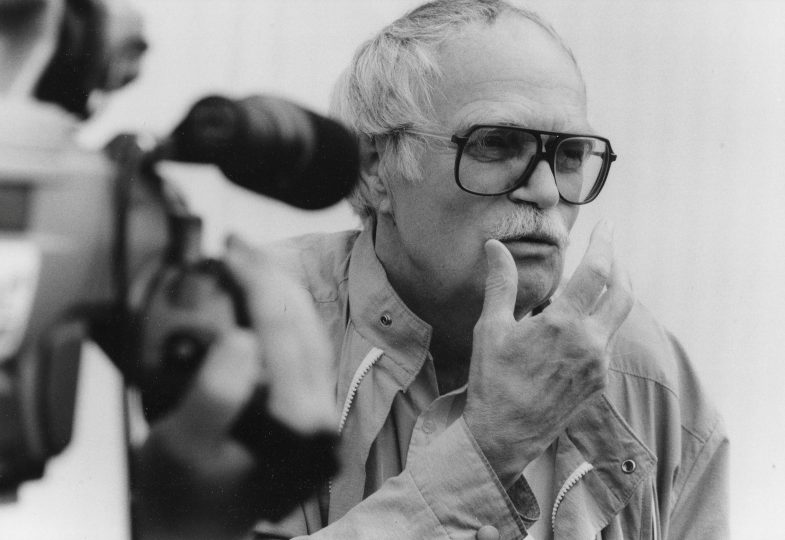

Thanks to the timeless interactive film, Činčera gained international renown, and the event marked the beginning of the second phase of his career, which took him around the world in order to prepare similar multimedia projects for various exhibitions. But Činčera experimented with the film medium and various genres already in his previous – documentary – work, characterised by distinct aesthetic elements, humour and thematic diversity ranging from natural history to physics to history to sociology to art.

Činčera was born in June 1923 in Brno. After high school, he completed a construction course because during the Protectorate, universities were closed and students were mostly sent to Germany for forced labour. Through scenographer Vladimír Vychodil’s intercession, Činčera was employed as a stage technician in the Beskydy Theatre in Hranice (the theatre later moved to Nový Jičín). After the war, Činčera studied theatre at Charles University in Prague.

His first experiences with film production came when he filled in for his dormitory roommate Vladimir Svitáček, who had a part-time job at the shoot of the nature documentary Flowers of the Tatras (Kvety Tatier, 1954). Svitáček eventually turned the job down, and Činčera filled in for him as the camera bearer. The film’s director, Karol Skřipský, offered the young assistant a dramaturge position in the Studio of Popular Science Films in Bratislava, where Činčera made a short school film about plant reproduction titled Why Do They Bloom (Prečo kvitnú, 1956).

After another intercession, this time by dramaturge Karel Kraus, Činčera became a dramaturge in the Studio of Popular Science Films in Prague, where he worked for instance on Miro Bernat’s acclaimed film about the children of the Terezín ghetto called Butterflies Do Not Live Here (Motýli tady nežijí, 1958). In addition to dramaturgy, Činčera also wrote scripts and commentaries (see the poetic film about the ocean surface movement Waves, the Language of the Sea [Vlny, řeč more, 1958]). When Václav Borovička took over the role of the Studio’s dramaturge, Činčera started directing his own films.

Dancing Around Dance (1960), which Činčera made with Rudolf Krejčík, is a documentary depicting the history of the rhythmical movement of human bodies in various cultures. Archive footage of diverse dances is accompanied by slightly sarcastic commentary read by Miloš Kopecký. Činčera re-used this unusual approach to an education film, which presents the information with (intellectual) humour instead of didactically, in his The Judgement of Paris (Paridův soud, 1962). The film with a subheading The Small History of Beauty uses live-action footage combined animation and archive footage to humorously explain the development of the perception of beauty and attraction.

The commentary to this stylised documentary is provided by actor Jan Přeučil, who, inspired by the mythological Paris, picks the most beautiful woman, a goddess, at a Prague swimming pool. This framework is lined by an explication of artistic styles and changing criteria of beauty throughout history – in prehistoric times, the baroque period and during the renaissance…

In the early 1960s, just like his fellow documentarists, Činčera searched for escapist topics far from the reaches of ideology. But at the same time, his films included multivalent allusions to the social and political situation. He realised that criticism of the system may be overlooked if uttered by small children. He used this approach for the first time as a dramaturge of What They Think of Us (Co si o nás myslí, 1958), which uses hidden cameras to capture the behaviour and opinions of children to provide an indirect insight into their homes.

The film That’s My Bucket (To je můj kyblíček, 1963) is a survey conducted among pre-school children who reveal their understanding of personal and social ownership.

-Who owns the tram?

-The state.

-Do you know what the state is?

-It’s where the trams stay at night.

The film showing how child psychology inclines towards private (i.e., capitalist) ownership was approved by the censorship committee without any reservations. It fulfilled the ambition Činčera mentioned in an interview with Martin Štoll: “The goal of honest documentarists was to avoid direct confrontation with the ideology and power, so we searched for escapist themes. But we often managed to include something the censorship committee overlooked in seemingly harmless films.”[1]

Činčera used the survey among children again in the films Citizenship: Child (Národnost dětská, 1965) and Forgotten Words (Zapomenutá slova, 1965). In the first one, he wanted to find out how Czech and Slovak children unburdened by various concepts and prejudice perceive terms such as “home” and “nation.” The children agreed that home is a place where one feels good. They don’t see it as a restricted space claimed by a certain group of people. When asked who owned the Tatras, their response was “Woods and animals.”

Činčera once again proved his extraordinary talent for work with children and the ability to understand their psyche and way of expressing themselves in Forgotten Words, a film made to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Czechoslovakia. In this film, Činčera confronted children with facts about the Second World War. Four Times and Again (Čtyříkrát o jednom, 1963) uses a playful form to draw attention to the unfair remunerations system of employees in state-owned companies.

Sometime in 1962, the method of film-truth became trendy in Czechoslovakia. Shooting on real locations without any script and staging, shifting the core of the directorial work from the space in front of the camera to the editing room… Also the audience is involved in the process of discovering reality. Činčera’s creative process is captured in his most acclaimed documentary Romeo and Juliet 63 (Romeo a Julie 63, 1964), which won awards in Bergamo, Oberhausen and Karlovy Vary.

Due to his original profession, Činčera looked for themes in the theatre and had lots of friends in the Theatre Institute. The Institute commissioned a methodological film about the directorial methods of director Otomar Krejča. In addition to several hours of study material for internal purposes of the Institute, a 60-minute-documentary for the cinemas was made. For five months, Činčera observed how Krejča and his actors rehearsed Shakespeare’s titular tragedy. Činčera tried to stay out of their way as much as possible but had to work with a heavy studio camera which was “about as suitable for capturing life naturally as an armoured vehicle for tracking wild animals.”[2]

The film begins with the premiere and then circles back to the first meeting of Krejča with Marie Tomášová and Jan Tříska, who played Juliet and Romeo, respectively. Footage of a weekend workshop at a cottage near the Sázava River was filmed with a concealed camera. Činčera and one of his cinematographers hid behind a window in a closet inside the cottage and the second cinematographer was stationed behind a basement window. The microphone was placed in a flower basket above a table at the veranda. Thanks to this approach, we don’t see actors rehearsing their roles, but rather a group of young people openly discussing their ideals. The film subsequently step by step captures their effort to unravel the essence of bringing the play to life: readthroughs, staging, dress rehearsals and the premiere in the National Theatre. The leitmotif of the preparations is the effort to shape the play in a way that would appeal to a contemporary audience, with focus mainly on the ideas of tolerance and defiance of hate.

The complexity and strenuousness of theatre work is further explored in The Fog (Mlha, 1966) dedicated to the staff of Theatre Na Zábradlí. Also in this case, Činčera made a study version for the Theatre Institute. But this time, he didn’t follow the process of staging a single play. Footage from rehearsals of various absurd dramas (The Bald Soprano, King Ubu, Waiting for Godot, The Garden Party – where we see a young Václav Havel) paint a picture of the theatre and the time, which the authors saw just as chaotic, complex and bitterly comical as the themes of the rehearsed plays themselves.

That’s why the film got its pessimistic title The Fog, alluding to obscurity and unintelligibility of social mechanisms. “In line with the dramaturgical direction of the Theatre Na Zábradlí, we see the start of the solution in naming the untransparency of the complex human and social fog in and around us. We believe that it’s a better way of art than singing about blue sky,” explained Činčera in an interview.[3]

Činčera managed to include a commentary on the conditions in Czechoslovakia in his travelogues, which he was able to film abroad after the period of political liberalisation in the 1960s. During their trip to the Edinburgh International Film, Theatre and Music Festival, Činčera and cinematographer Jan Špáta made Rebels and Bowler Hats (Buřiči a buřinky, 1965). In this documentary, he creates contrast between orderly clerks in bowler hats and rebellious long-haired youth finding themselves on the crossroads both in real life and metaphorically. “What’s happened to young people?”, asks the narrator.

This dynamical report has a similarly sceptical message as The Fog when ended by words of a policeman convinced that young people will outgrow their desire to change the world, put on bowler hats, and nostalgically remember the time they had long hair. While in Scotland, Činčera also made the documentary essay Looking Over the Fence (Pohled přes plot). It shows that fences in the country don’t have a protective and defensive purpose but work as a social contract: this is my land where you are welcome if I invite you. A portrait of a life in a distant country once again reflects the worries of Czechs and Slovaks.

One of Činčera’s last documentaries was Our Man in Hawaii (Náš člověk na Havaji, 1969), a profile of a Czech native named Kozelka, a former US Army Officer who served in Germany, Japan and the Philippines, and eventually ended up in Hawaii. “I think as an American, but speak as a Czech,” explains Kozelka in his broken Czech. Crystal clear water, sweet idleness, good food reminding him of home. His life on Oahu is a paradise.

But this time, the censorship committee took action. Not because Činčera showed how pleasant a life abroad can be for an emigree or because it provocatively mentions a “small and not very happy country” in Central Europe, but because it showed luxurious cars cruising through the streets of Hawaii.

The time when Činčera was allowed to make basically anything he wanted was over. But after the success of Kinoautomat, his career gravitated towards pioneering inventions and audiovisual projects. There wasn’t much for him to do with regards to film direction during the period of Normalisation. But he became known abroad as an award-winning author of multimedia shows.

In Australia, Spain and Japan, he inventively combined film elements with scenographic and architectonic ones in order to create a unique experience. To create a kaleidoscopic effect, he had a mirror hall built. In films made with cinematographer Jan Malíř, he used special effects such as chroma keying. In his Kinolabyrint for Expo 90 in Osaka, the viewers could choose between two doors leading to various screening halls. In the end, they all met in the same circular room.

In addition to using Laterna Magika and Kinoautomat principles in his programmes, Činčera kept reaching back to documentary methods and tried to create a poetic and truthful depiction of reality because, as he once said, “being a documentarist isn’t an occupation, but a way of seeing the world”.[4]

Literature:

Lucie Česálková, Atomy věčnosti. Český krátký film 30. až 50. let. Prague: Národní filmový archiv 2014.

Lucie Česálková, Kateřina Svatoňová, Diktátor času: (De)kontextualizace fenoménu Laterny magiky. Prague: Národní filmový archiv, Charles University 2019.

Radúz Činčera, Režie v dokumentárním filmu ve světovém vývoji. Krátký film 1964–1965. Prague: Ústřední ředitelství Československého filmu – Filmový ústav 1965, pp. 24–25.

Radúz Činčera, Romeo a Julie 63 v zápiscích režisérových. Kino 19, 1964, no. 11 (4th June), p. 7.

Jiří Hrbas, Film se obdivuje divadlu. Divadelní noviny 10, 1966, no. 3 (5th October), p. 4.

Eva Jelínková, Interview with Radúz Činčera. Kinorevue 1, 1991, no. 2 (22nd January), p. 11.

Antonín Navrátil, Cesty k pravdě či lži. Prague: Akademie múzických umění 2002.

Jana Patočková (ed.), Divadelní ústav 1959–2009. Prague: Institut umění – Divadelní ústav 2009.

Martin Štoll, In Memoriam. Dva rozhovory Martina Štolla s Radúzem Činčerou. Film a doba 45, 2000, no. 1., pp. 27–28.

Notes:

[1] Martin Štoll, In Memoriam. Dva rozhovory Martina Štolla s Radúzem Činčerou. Film a doba 45, 2000, no. 1, p. 27

[2] Radúz Činčera, Romeo a Julie 63 v zápiscích režisérových. Kino 19, 1964, no. 11 (4th June), p. 7.

[3] Jiří Hrbas, Film se obdivuje divadlu. Divadelní noviny 10, 1966, no. 3 (5th October), p. 4.

[4] Jelínková, Eva, Rozhovor s Radúzem Činčerou. In Kinorevue, y. 1, no. 2 (22nd January), 1991, p. 11.