The silent film Amazon: Longest River in the World (Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo, 1918–1920) is a key piece of work in the history of Brazilian documentary film that, until recently, had been considered lost. For several decades, it had been classified as a 1925 US film in the collection of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague.[1] Having previous experience with foreign travel documentaries from the same period, the film curator Iwona Łyko suspected that it probably hadn’t been produced in the US. Watching the film, she noticed the coherent concept of the work and that the author must have known the environment very well. That’s why she joined forces with the US curator Jay Weissberg, who then theorised that it might be the lost Brazilian film directed by Silvino Simões Santos Silva (1886–1970). The fact that the missing film Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo had been preserved in Prague was confirmed by Cinemateca Brasileira and the researcher Sávio Luís Stoco from Universidade Federal do Pará.[2]

The fate of the film’s author is tied to the rubber rush and the city of Manaus. During his career, he made 83 short films, 8 feature films, and 5 medium-length films.[3] In Brazil, he was making commissioned films for private companies and the Brazilian government, and in the 1920s and 1930s, he also worked in Portugal, making for instance Miss Portugal (1927) and Terra portuguesa (1934). Popular was his feature-length documentary film No Paiz das Amazonas (In the Country of the Amazons, 1921/1922).[4] Silvino Santos was born in Portugal but already at the age of thirteen has left for a job in the northern Brazil. He worked as a salesman, while trying to find work as a painter and photographer. At the time, the Amazon city of Manaus in the Brazilian inland was getting rich very quickly thanks to the tapping of natural rubber,[5] being in great demand with the development of cycling and car transport. However, it was not easy to extract rubber latex in the forest. To collect it, the seringueiros or borracheiros had to cut a path through thick undergrowth, travelling long distances as the intact system of the Amazon forest contained only one to two rubber trees per hectare.[6] Life in this part of the Amazon was also made very difficult for the tappers by other climatic conditions, such as the alternation of dry and wet seasons (during the wet season, the extraction was nearly impossible), humidity, heat, and tropical diseases. Many seringueiros died of fever, malnutrition, due to animal attack, snake bite, or after falling from great heights when cutting into a tree. In the camps, there was not enough quinine to treat malaria, and poor hygienic conditions contributed to the spread of other diseases. Children born in isolated tapper camps did not have access to schooling and often remained illiterate. Seringueiros weren’t employed; they only got a percentage of the price at which the dealer later sold the rubber.[7] It was often those who had exhausted all other options who were willing to work under such conditions.[8] The Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company got the scarce cheap labour by enslaving original indigenous people. As such, it could make the most of the newly acquired land as its owner was right to worry that rubber cultivation would soon be moved to South-East Asia.[9] Around the Putumayo River at the border of Peru and Colombia, people from the Uitoto, Muinane, Bora, Okaina and other communities were forced to tap rubber under the threat of physical punishment, torture, rape and even murder. The estimated number of original inhabitants having died in camps around the Putumayo River varies in different sources but amounted to several tens of thousands of victims. The infamous practices of the Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company and its owner, the Peruvian politician and businessman Julio César Arana, went down in history as the “Putumayo genocide”.[10]

J. C. Arana contacted Silvino Santos in Manaus in 1910, sending him, an amateur interested in photography, on an internship to the Parisian Pathé-frères film studios. Here, Santos learnt the basics of filmmaking and got the necessary equipment for shooting his first films.[11] In 1912, the book The Putumayo: The Devil’s Paradise by the US engineer Walt Hardenburg was published in Britain, in which the traveller described the way Arana’s company acted at the rubber tapping location.[12] The company was based in London, and that’s why the judicial proceedings and fights for the favour of shareholders didn’t take place in Brazil or Peru, but on British soil. The newly trained director Silvino Santos set sail from Paris back to Brazil and in 1913, he was shooting for Arana around the Putumayo River (at that time, he was already married to Arana’s adopted daughter, Ana Maria). The film was called Rio Putumayo and was made with a clear purpose: to give the foreign shareholders of the Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company a positive impression of the rubber industry[13] and its “civilizing” mission, with which the company justified its actions in the region, among other things. The photos by Santos for Arana of indigenous peoples of the Amazon served a similar purpose. According to the director’s unpublished autobiography Romance da minha vida (1969), the film was destroyed, but it is possible that fragments (capturing for instance the Uitoto community) appeared in Santos’ later film Amazon: Longest River in the World. After the Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company was dissolved by court action, Arana maintained his high social standing in the South American region and substantial property and was never punished for the crimes he had committed.[14]

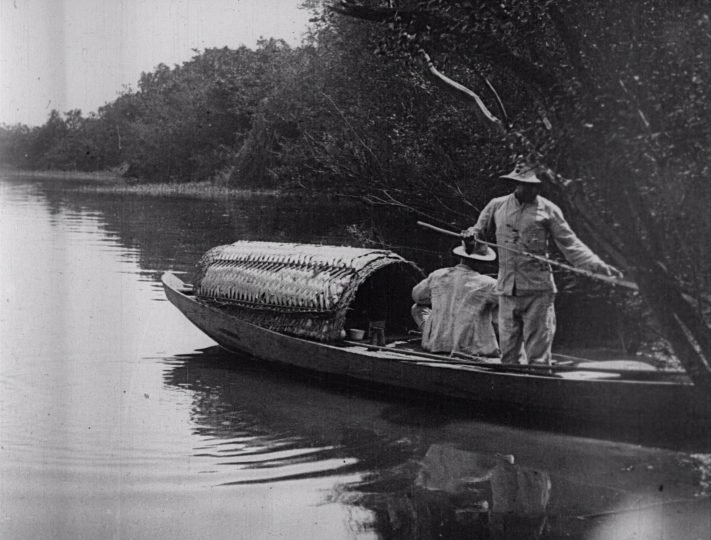

It was Amazon: Longest River in the World that Silvino Santos directed next. The film makes the best of the Amazon nature: meat, skins, rubber, and other raw materials are complemented by shots of indigenous people of the Amazon, its fauna and flora and towns, described by Czech intertitles as “more civilized”. In 1924, Film magazine promotes the work with an exoticizing description: “In addition to hunting adventures, the film also contains valuable examples of local plants, birds, and animals. What we see is the fabulous wealth of countries abounding in rubber, tortoiseshell, silk, fish, etc. A chapter in itself is the ruling tribe of armed women, called the Amazons.”[15]

Silvino Santos gave the film negative to the typing teacher Propércio de Mello Saraiva, who left Brazil with it promising to make copies and introduce the film to European audiences. To understand why Santos entrusted his work to Saraiva, it is necessary to understand the relationship of the Manaus rubber elite to Europe in the 1920s. “Paris in the tropics”, as Manaus wanted to be viewed, was bombarded by orders of European products[16] and, among other things, the luxurious Teatro Amazonas city theatre was built here in Art Nouveau style.[17] And when there was a chance to present an original piece of work made in the Amazon to European audiences, the Manaus shareholders of Santos’ film probably considered this an important milestone.

It was through Propércio de Mello Saraiva that Amazon: Longest River in the World arrived in Europe in the early 1920s.[18] A nitrous toned copy with Czech intertitles was made for Czechoslovak distribution. The press of 1924 describes the work as a new film by the R. Ehrlich a spol. film and rental company and an “adventurous film made by professor Saraiva on an expedition along the entire Amazon River”.[19] Outside of Brazil, Propércio de Mello Saraiva probably passed the film off as his own, concealing the true author. In the next decade, the film was lost from distribution and until his death in 1970, the director Silvino Santos, having permanently settled in Manaus, didn’t have a chance to see his work. The film was later archived in Národní filmový archiv on acetate material, and the original nitrous copy hasn’t been preserved. Amazon: Longest River in the World is now coming back to its country of origin in a digital version, and Cinemateca Brasileira and the local research community can examine and critically analyse it.

Notes:

[1] In this form, the audience of the Ponrepo Cinema could watch it in 2021 as part of the Film and Climate cycle accompanied by live music by Alexandra Cihanská Machová.

[2] Sávio Luís Stoco wrote a dissertation about Silvino Santos’ films entitled O Cinema de Silvino Santos (1918–1922) e a representação amazônica: história, arte e sociedade, which will soon be published in book form. This article draws on his valuable research as well.

[3] Sávio Luís Stoco, O Cinema de Silvino Santos (1918–1922) e a representação amazônica: história, arte e sociedade. São Paulo: USP 2019, p. 12.

[4] Ibid, p. 93.

[5] E. Bradford Burns, Manaus, 1910: Portrait of a Boom Town. Journal of Inter-American Studies, Cambridge University Press 1965, p. 400.

[6] The fact that in Brazil rubber trees did not grow in isolation, but were surrounded by other plants, protected them against the microscopic fungus Microcyclus ulei, causing defoliation. The fungus later taught a lesson to the American businessman Henry Ford, who in the late 1920s decided to buy a part of the forest in the Brazilian region of Pará, had it burned down, and found there a city with an adjacent plantation. However, due to Microcyclus ulei, artificial planting of rubber trees using the plantation system allowing for more efficient extraction didn’t work in Brazil, and Fordlândia was thus doomed from the start. See Greg Grandin, The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. New York: Picador 2010 (online).

[7] Established in Brazil, this practice was then transferred to the plantations of South-East Asia, where it is still common today. As a result, any drop in redemption prices means a reduction of the already very low earnings of rubber tappers.

[8] John Tully, The Devil’s Milk: A social history of rubber. New York: Monthly Review Press 2011, pp. 78–81.

[9] Ibid, p. 87.

[10] Ibid, p. 86. According to The Devil’s Milk, 32,000 people, mostly from the Uitoto community, died in the rubber camps around the Putumayo River; according to Imaginário e imágenes de la época del caucho: Los sucesos del Putumayo, there were 30,000 victims between 1903–1910.

[11] J. P. Chaumeil, Guerra de Imágenes en el Putumayo (1902–1920). In: Alberto Chirif, Manuel Cornejo Chaparro (eds.), Imaginário e imágenes de la época del caucho: Los sucesos del Putumayo. Lima: CAAAP, Kopenhagen: IWGIA, San Juan – Iquitos: UPC 2009, p. 53.

[12] Ibid, p. 40.

[13] Ibid, p. 54.

[14] Ibid, pp. 98–99.

[15] Film 4, 1924, p. 4.

[16] E. Bradford Burns, c. d., p. 403.

[17] A shot of the then new architectonic monument of the city also appears in Amazon: Longest River in the World.

[18] Sávio Luís Stoco, c. d., p. 139.

[19] Film 4, 1924, p. 4.