A reflexive film, such as Daleká cesta (Distant Journey, 1948)[1] by Alfréd Radok, also needs a reflexive film theory. There are numerous well-trodden paths for interpreting this canonical film, progressing from the horrors of Nazism, war and the Holocaust to the universal fate of humanity.[2] And since the extreme theme is combined with a distinctive, prominent form, such interpretations generally do not fail to mention the “expressionist” camera and mise-en-scene or “documentary” clips from newsreels and Nazi propaganda.[3] All these motifs can be seen in the film, and yet one could further question the media techniques that frame our vision of Radok’s comprehensively built world.

In a few precisely selected moments, a “trick montage”,[4] namely the interaction between larger and smaller image on one surface, becomes such a technique – from today’s point of view nearest to the term “split-screen”. Fictional events shift into a small frame in the lower right corner while documentary and newsreel shots of war destruction, Nazi emblems, and anti-Jewish terror emerge in the background. Although these moments intrude into the film only a few times and never last more than half a minute, in a way they do form the top of Radok’s multi-layered mosaic. Documentary and fictional, or “big” and “small” history of the Holocaust, collide in one cinematic shot – on one level of meaning – but equally important is the regime of seeing that allows comparison of these different registers of reality.

When Radok describes how horrible yet strangely fascinating the footage of the Polish patriots seemed when manipulated in the editing room,[5] he suggests that the editor’s double vision is a way to save the Holocaust tragedy for at least a moment from predestination – whether historical or narrative. The distribution of attention between the thumbnail and the enlargement reveals documentary and fiction as two forms of determinism whose truth lies in permeating one another. In this principle, the presence of a meta-view, the way a moving image can analyse itself, becomes manifest, including both the conditions in which it is formed and received. However, to fulfil this role, it must be freed from an overly specific fictional world and embrace both.

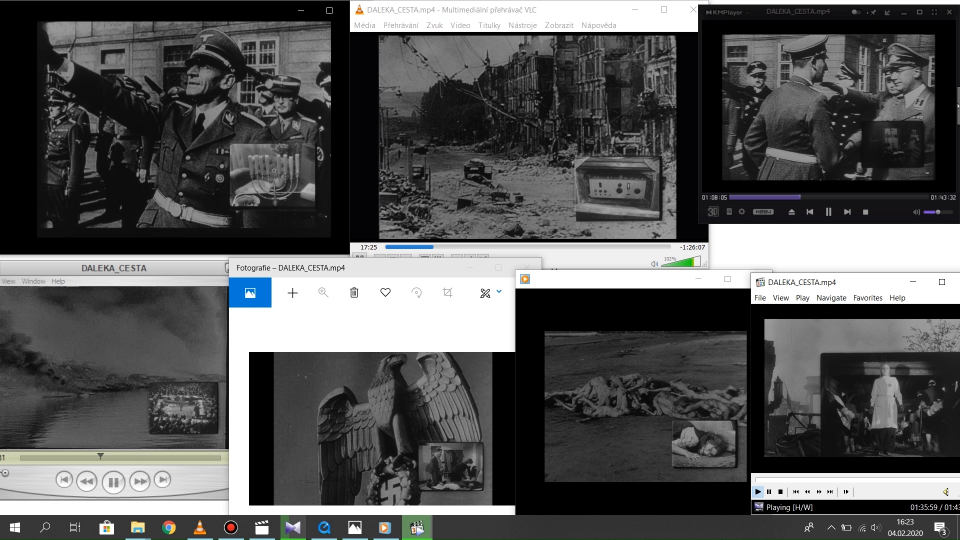

To this end, two works were created – one is audiovisual, included in the bonus features of the Blu-ray edition,[6] and one is the text that you are now reading. With slight exaggeration, their relationship can be perceived as akin to the interaction between two frames in Radok’s film. From the existing textual reflections of Distant Journey, a poetic-research video emerges that extends the reflexive movement of the film into the interface of the computer desktop and video-editing software. This form conveys the epistemic conditions of watching and analysing films in the digital space, and at the same time conjectures Radok’s idea of trick montage and his aforementioned editing experience into the consequences. However, video still needs the printed word for moments when the language of images and sounds becomes too immersive or too confusing. The main task of the text, therefore, is to clarify the terms and ideas that give the media-reflexive play with split-screens and pop-up windows a positive content.

First, we must return to the intention from which the picture originated. The use of split-screen and other media-reflexive elements relates to Radok’s vision of “artistic report” and the ideal film as a multidimensional structure in which “a realistically descriptive layer and a markedly stylised layer would permeate”, allowing comparisons of the points of view.[7] Radok was not given the opportunity to fully apply this idea in the film medium (he rather developed it in “polyecran” projections at the experimental theatre Laterna Magika;[8] nevertheless, the concurrency of various layers of reality already appears here in prototype form. Neither documentary nor fiction exists in some sort of imaginary pure state, but in comparison. The artistic report can only emerge when reality is permeated by the powers of the false, and at the same time when the narration refers to a space beyond its horizon.

More specifically, the reportage construction of the work can be divided into three levels. The first involves the story of Hana Kaufmannová, a Jewish doctor struggling to survive in Nazi-occupied Prague. The melodramatic undertones of a love triangle and Hana’s mixed marriage with her colleague Toník are almost the only aspects that temporarily diminish the existential fear of randomly arriving transports, even at the cost of lightening the tone of the film. The second level, let’s say an expressionist one, comes when this fear is realised. It depicts a deformed reality in the unbearably claustrophobic Terezín concentration camp, but also its harbingers, which the characters have sensed all along. If the expressionist scenes at least indicate what is representative of the horrific experience of the Holocaust, the third level of the film, which consists of the trick sequences, represents the historical context outside the fictional frame. However, even this level cannot be seen in isolation, so as not to result in dry historicism or indistinguishable abstraction. A frame must be preserved, but in a form where one image will not suffice – this is when the picture-in-picture or, in our terms, split-screen comes in.

The first split-screen appears at the end of the second sequence of the film. It closes a series of scenes from Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda documentary Triumph of the Will (1935), which Radok inserts in the film. Although this passage transcends the fictional plot, it implicitly returns to it. The vigorous marching of Nazi soldiers, which begins the archival sequence, immediately responds to the sluggish procession of Jews in silhouette in the opening title sequence – two separate actions, deportation and mobilisation, are pitted against each other. Other scenes continue in this alienating spirit: shots of military marches, speeches by Nazi leaders and heiling crowds are accompanied by an ironic commentary that deliberately puts these monumental scenes down. Even the newsreel footage of war destruction and concentration camps, subversively cut into the sequence, does not fit into the world of Nazi propaganda.

Then comes something totally incongruous: a shot of a procession in front of the main Terezín gate, which is neither part of Triumph of the Will nor of the newsreels. When the same scene is repeated later in the fictional story, the reportage mystification is revealed – the archival sequence contains elements of falsification that extend the frightening harbinger of the Holocaust to the macro-historic and micro-historic levels. The falsified moments of all these types gradually converge until they implode… The final link between the fading “documentary” with the forthcoming fictitious shot in split-screen is thus, in a sense, a logical progression.

How can this sequence be explained through the optics of film theory? A strong starting point is offered by Jaimie Baron, who in her book The Archive Effect writes of a “false archive effect”. If the archive effect is generally based on the viewers’ confidence they are watching an authentic imprint of the past, a false archive effect arises when the film creates the impression that we are observing authentic archival footage, even if it is not.[9] A snapshot of this effect can be achieved in various ways, such as via fictional reenactments or the manipulation of archival material, often so as to challenge the claim of any visual representation to exclusive truth.[10] The mocking commentary, embedded newsreel footage and staged documentary moments provide an illustrative example of this effect – they break not only the uniform language of Nazi ideology but also its spatio-temporal coordinates, which now inescapably veer from the traces of the former presence to a (self)destructive outcome.

However, a truly unique case of the false archive effect comes in sequences where documentary and fictional moments appear together on one screen. In total, there are seven split-screen sequences in the film: each is triggered by a symbolic moment in the fictional story (close-up of a menorah, Professor Reiter’s suicide, a Terezín prisoner being trod upon in the mud etc.), which gradually diminishes and frees up much of the space of the scene for the wartime newsreels, and, after a short interval, returns to the fiction interface. The main thing that connects the sequences is not the possibility to track big and small history on one screen. Even the subversive montage of newsreels or the spectacular freezings of events at key moments are not, in themselves, crucial. From the point of view of the false archive effect, the main thing is that the viewer gains a relatively significant freedom to search for similarities and differences between the documentary and fictional levels.

For example, the third split-screen sequence can be interpreted from the perspective of tension between that which is present and that which is absent. It begins with a shot of a darkened room with an open window, from which Professor Reiter has just jumped to his death after receiving his notice for “relocation” to Terezín. This disturbing absence contrasts with the emerging newsreel footage of Reinhard Heydrich’s accession to the role of Reichsprotektor in Prague, which, through the Nazi salutes and fluttering swastikas, shows the superiority of the occupiers spectacularly. Roughly halfway through, however, the roles reverse: the plot shifts from the professor’s tragedy to a relatively banal scene (Toník taking off his socks), while the archival footage moves to the suggestive panorama of concentration camps. The interplay of the visible and the invisible, the concrete and the abstract, thereby takes place alternately on both fronts.

The sixth split-screen demonstrates how one eloquent gesture can encompass the entire trajectory of National Socialism. Through the trick montage, the screaming face of a Terezín prisoner crushed into the mud is opened both onto the past and onto the future. While stone swastikas and golden eagles highlight the mythical roots of Nazism, the shots of corpses from concentration camps, which regularly alternate with the Nazi icons, suggest where the ideology will lead in the end. The suffering of the heroine in the miniature is thus complemented by the perverse “before” and “after”.

It is in the final split-screen that the most powerful link between the archival and the fictional occurs. Hana defiantly walking in white despite the masses going to their deaths, and newsreel footage of the Red Army’s conquest of Berlin, both serve to herald the coming liberation of the Jews. As tanks and planes arrive and prisoners seek rescue outside the camp walls, it is clear that the archival footage and the fictional presence will soon be joined. Even this moment of fusion, however, has a subversive flavour – instead of the tanks and planes only a single motorcycle arrives.

Thus, the false archive effect of Distant Journey arises not only from manipulation, but from a technique of vision that allows you to continually monitor the changing relationships between the two visions of the Holocaust. Reality is revealed to us neither by documentary nor fiction, but through their mutual entanglement. Rather than unravelling it, we should try to actualise the possibilities hidden within it, seek ways to liberate the reflexivity of the film from a particular fictional universe, and translate it into the way we see the world.

Notes:

[1] The year 1948 features in the opening titles, but the film was supposedly still being edited in early 1949 and was not released until June of that year. For the circumstances of the distribution of Distant Journey, see e.g. Jan Láníček – Stuart Liebman, A Closer Look at Alfred Radok’s Film Distant Journey. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 30, 2016, no. 1, pp. 53–80.

[2] Probably the best-known interpretations of this film are two studies by Jiří Cieslar from the early 1990s, which were later condensed and adapted into English: Jiří Cieslar, Living with the Long Journey: Alfréd Radok’s Daleká cesta. Central Europe Review 3, 2001, no. 20. Online: <https://www.pecina.cz/files/www.ce-review.org/01/20/kinoeye20_cieslar.html>, accessed January 31, 2020. Both studies were also published in the volume Alfréd Radok mezi filmem a divadlem edited by Eva Stehlíková (Praha: Národní filmový archiv – Akademie múzických umění 2007).

[3] For more on the film’s expressionist allusions, see, for example, André Bazin, The Ghetto as Concentration Camp: Alfréd Radok’s The Long Journey. In: Bert Cardullo (ed.), Bazin on Global Cinema, 1948–1958. Austin: University of Texas Press 2014, pp. 92–96. The documentary sequences are explored in: Aaron Kerner, Film and the Holocaust: New Perspectives on Dramas, Documentaries, and Experimental Films. London and New York: Continuum 2011, pp. 21–26.

[4] This expression is used in the technical screenplay, see Mojmír Drvota – Alfréd Radok. Daleká cesta (technický scénář). Praha: Státní výroba dlouhých hraných filmů 1948. For the circumstances behind the screenplay development, see Lea Mohylová, Vývoj filmové idey snímku Daleká cesta v intencích autorského záměru Alfréda Radoka. In: Andrea Schnapková, Zdeněk Hudec a kol., Daleká cesta: Kritické a analytické studie. Praha: Casablanca 2018.

[5] Archiv divadelního oddělení Národního muzea v Praze, Přírůstek 15/90, 15/2004 – Alfréd Radok, kart. 12. Poznámky k připravované premiéře filmu Daleká cesta, 1949, p. 1.

[6] Jiří Anger – Jiří Žák, Distant Journey Through the Desktop. In: Jiří Anger (ed.), Daleká cesta / Distant Journey [Blu-ray]. Praha: Národní filmový archiv 2020.

[7] Quoted from: Jiří Cieslar, Daleká cesta Alfréda Radoka. In: Eva Stehlíková (ed.), Alfréd Radok mezi filmem a divadlem. Praha: Národní filmový archiv – Akademie múzických umění 2007, pp. 11–12. See also DO NM, Poznámky k připravované premiéře filmu Daleká cesta, 1949, p. 1.

[8] For more on the polyecran projections at Laterna Magika, see Lucie Česálková – Kateřina Svatoňová, The Dictator of Time: (De)contextualizing the Phenomenon of Laterna Magika. Praha: Národní filmový archiv – Filozofická fakulta UK 2019, esp. pp. 50–53, 86–87.

[9] Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. London and New York: Routledge 2014, pp. 50–51.

[10] These specific procedures are discussed, for example, in Alex W. Bordino, Found Footage, False Archives, and Historiography in Oliver Stone’s JFK. The Journal of American Culture 42, 2019, no. 2, pp. 112–120.