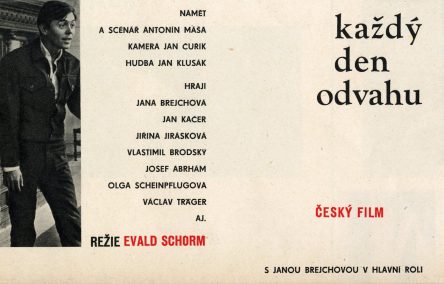

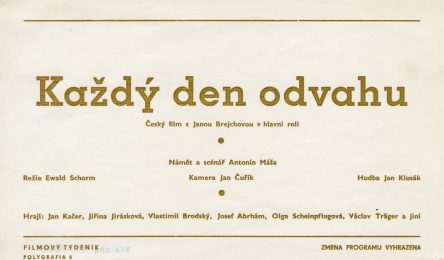

In his first feature film, Evald Schorm drew a portrait of a man facing his own limitations, in values and intellect. Schorm co-wrote the script with Antonín Máša. Since the film was supposed to be about small town youth, Máša started visiting schools, student halls of residence and various workplaces as well as meeting members of the State Security police specializing in juvenile delinquency.

During this research, Máša saw a popular Socialist Youth functionary in one of the plants. He found his life story so interesting that he and Schorm decided to base the emerging script on the functionary. The first version of the script was finished in autumn 1962. However, it took more than a year and another six versions of the script until everybody involved – Máša and Schorm, as well as the Barrandov Studio script editors – was happy with the final version, completed in December 1963.

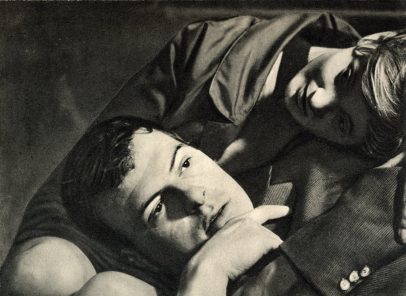

Jarda Lukáš (Jan Kačer), a former Socialist Youth Movement functionary, udarnik (“shock worker”) and National Security Corps member, had been devoted to communist ideals. In the new era he lives in, the cult of personality no longer exists and the myths that emerged after the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état have been dispelled. Jarda realizes that the words he used to believe in no longer carry their former weight. He does not think, though, that he has made a mistake. Instead, he views his friends and society as mistaken. The people around Jarda do not share his beliefs nor do they support or understand him. He feels deeply alienated since, in his view, the purposes of work and human existence are conjoined.

The socially engaged dogmatist faces both a political and a personal crisis forcing him to search – to search for an anchorage, for a place of his own in the ever-changing world, for the purpose of existence, for a reason to keep fighting despite his doubts, mistrust and loss of any supporting network. Like in other films by Schorm, the crisis of an individual reflects the crisis of society as a whole. The nonschematic drama offers no unequivocal solution to the protagonist’s fight. That is why some viewers criticised the film for only depicting “real life” but not the way people should live, as had been the norm with films from the working environment.

Courage for Every Day (Každý den odvahu) is reminiscent of Schorm’s documentaries not only thanks to the existentialist theme but also thanks to the non-moralizing, observational style also applied by other directors of his generation, such as Miloš Forman and Ivan Passer, although to a different effect and with a more detached view. Yet while the films by these directors show characteristic styles of their own, it is mainly Shorm’s interest in contemporary society, the ethical and philosophical questions depicted, and the director’s approach to the characters that links his films together.

Courage for Every Day was shot between April and July 1964. Even though the film was screened for the first time already in January 1965, it was not distributed until September 1965. Originally, the film was supposed to both start and end with a quote from Kafka’s fable The Vulture, but this did not stand well with Antonín Novotný. So Kafka had to be replaced by Jerzy Andrzejewski and his Ashes and Diamonds, which was one of the reasons why it took the film, criticized for the depiction of “hopelessness and futility”, almost a year to be distributed.

Some critics found the film too serious, constrained and overly thesis-based (which was repeated many times with other films by Schorm; despite that, the bitter psychological drama was awarded the Czechoslovakian Film Critics’ Awards in 1965). Nonetheless, journalists were not allowed to write about it. The film was further awarded with both the Overall Winner Award and the Audience Award in Pesaro, Italy, in 1965 and with the Grand Prize in Locarno, Switzerland. It was also screened within the Critics’ Week at Cannes. But the critics were better prepared for the film than the audience – only about 360,000 viewers came to see it.

Apart from the film’s overall bitterness , provoking not only with the forceful depiction of the inner tragedy of an individual, but also with too much nudity, violence, and informal speech, the low turnout stemmed from the limited distribution. After having been shown in the Paříž cinema in Prague for a week, the film was then screened only in several marginal cinemas. However, nowadays it is appreciated as one of the most valuable films of the Czechoslovakian New Wave thanks to the Shorm’s uncompromising and piercing critical eye.

Martin Šrajer