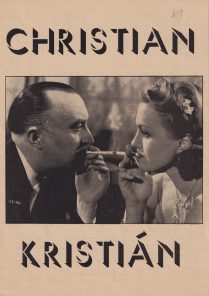

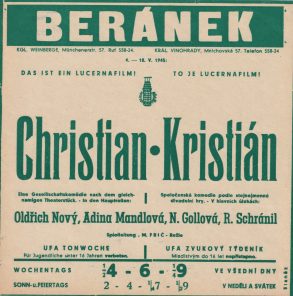

Just like other stars of the First Republic, Oldřich Nový also formed his image through the media – in theatre, film and on LPs. His current image as a star, however, is derived mainly from his film roles, for which he is most often remembered. Especially during national holidays, the likelihood of seeing Nový as a sensitive, charming, fit lover wooing a lady rises rapidly when you turn on the TV. But this popular actor didn’t find his ideal character right away. The turning point came with his role in Kristian, which, with its premiere in September 1939, was one of the first and biggest film events of Protectorate-era cinematography.

The film’s success is not the result of coincidence, as sometimes happens, but of careful calculation. Kristian was based on the comedy Christian by the French playwright Yvan Noé, which had already been a success in the mid-1930s when it was performed on the Vinohrady theatre scene. While the director Martin Frič did choose the theme at random, together with screenwriters Josef Gruss and Eduard Šimáček, and probably with the help of Oldřich Nový, he made considerable changes. He adapted the characters and the setting to Czech circumstances and the nature of the actors. Even the pessimistic ending was changed at the last minute. Originally, Kristian was supposed to end with the protagonist’s divorce.

In the 1930s, Nový would appear in film and theatre in the roles of various tricksters who do not play fair with others. Kristian partly follows this pattern. At the same time, there is a certain romanticization of deception. The main character is the downtrodden travel agency clerk Alois Novák. At work he obediently fulfils the wishes of his customers and the manager, and at home he just as submissively submits to the routine expected by his wife Marie (played by Nataša Gollová). He breaks out of the stereotype by frequenting the Orient Bar, where he seduces other women with the intention of spending the night with them (which, of course, he fails to achieve – and perhaps he wouldn’t even have the courage to actually do). Nonetheless, towards that end, he very consistently creates a complete alternate identity.

When Alois arrives at his favourite establishment in the opening scene, the staff address him respect, believing him to be an engineer, factory owner or general manager. In any case, he is Kristian to them – and to the audience, at first. The cleverly constructed script only reveals the true face of the dashing bon vivant half an hour into the movie. Till then, we are held under the illusion, along with the other film characters, that we are watching a famous figure of Prague nightlife. The opening introduction of the hero contributes to this. First, we only see his legs, then his torso in a perfectly fitting suit. We hear how he is greeted by everyone. Only then does he stop at the mirror to check that his appearance is tip-top from head to toe, and we finally get to see the mythical figure in all his splendour.

Kristian is greeted with a drink at the bar and seated at a table by a trio of keen waiters.

Additional clues reveal that he is no ordinary guest, but a distinguished one, worthy of the most exquisite service. Kristian is unfazed, as if he were used to this level of admiration and flattery. In reality, this is just a perfectly learned role, the execution of a clearly written script. His next stage is to find his prey. For this evening, it is Zuzana (Adina Mandlová), a bored woman from high society who, in her white dress (from the renowned salon of Hana Podolská), sparkles across a room filled exclusively with people in black outfits. No wonder Kristian can’t take his eyes off her.

Oldřich Nový was also famous for sticking faithfully to the script. He would practice every gesture and line, and he is said to have calculated exactly how many steps Kristian had to take during his flamboyant entrée to ensure that it had the right rhythm and that he radiated dignity at all times. His thorough preparation came in handy considering the hectic filming, which took just 23 days (and it wasn’t just for Kristian – this was standard production time in its day). Furthermore, the highly efficient Martin Frič only did one or two takes for most shots. Perhaps this is why the film occasionally has distracting jumps across the timeline and why the continuity of some of the shots falters.

It was also Nový, who was 40 at the time of filming, who reportedly pressed for both acting partners, 29-year-old Adina Mandlová and 27-year-old Natasha Gollová, despite Frič’s reservations. Kristian lusts after the former, and she initially succumbs to him. But when Zuzana learns that the strapping, handsome man with the flawless diction is actually the perpetually crouching, mumbling Alois, he ceases to be attractive to her. Instead, she sets the rules of the game and starts to plot how to punish the two-faced womanizer. The other woman, on the other hand, must embody what the protagonist desires. Until that point, she is almost invisible to him as the bland Marie, who is most excited by an evening game of dominoes. It is only when she becomes an attractive modern woman with the help of her impertinent aunt („No wonder she doesn’t want you!“) that the marriage regains its lost sparkle.

When Marie, in turn, asks Alois at the end to show her a bit of Kristian, presumably to indulge her fantasy for a change, her husband resists. He abandons the role of the assertive, almost aggressive seducer who does not respect personal space and explicit or implicit appeals from women to leave them alone forever. As much as the figure of Kristian is etched in the general consciousness as a model of First Republic gentility and gentlemanliness, today the response to his „pick-up“ techniques would probably not be a gradual melting of the heart, but a dose of pepper spray to the face.

Kristian ignores Zuzana’s request to leave, and instead audaciously sits even closer to her. When the annoyed victim wants to leave the bar, Kristian takes her to the dance floor without asking. He disregards her pleas to let her go. He deliberately takes advantage of her fear of shouting out and attracting unwanted attention. Later, Kristian argues over Zuzana with her current suitor, Fred. She is a mindless object for them to be used either by one man or the other. Nobody asks her what or whom she wants.

The initial seduction of Zuzana continues in the private lounge, where the tone of the conversation changes. She allows Kristian to come increasingly closer, he circles around her like a hungry vulture, with pretty words (the falsehood of which will soon be unmasked) as he tries to win her favour. At times playful, at times chilling, the courtship – reminiscent of American screwball comedies such as Bringing Up Baby – culminates in an almost erotic, intimate close-up lighting of one cigarette against another. A similar deviation from the dominant tone occurs again during the sentimental ending, apparently a remnant of the originally sad ending, when Alois self-pityingly accepts his defeat and the prospect of a solitary existence, and the dynamic comedy of confusion becomes, for a moment, a melodrama.

In the audience’s reactions to Kristian, one may come across the interpretation that Alois started spending his evenings with other women because his wife bored him. But the film shows that they are both boring, and Marie would have an equally compelling reason to create an alter ego living a lavish nightlife like her husband. Just as Kristian reiterates certain tried-and-tested catchphrases (e.g. „Close your eyes, I’m leaving“), Alois is also a man of habit. In the travel agency, he answers customers‘ questions with memorized phrases that, due to unclear breaks between the words, merge into one big, suffocating entangled noise. He is suffocating in his marriage but does nothing to revive it. On the contrary, he cowardly flees from it. At home, he just eases into his slippers and starts playing dominoes. It would be unfair to blame Marie for the greyness of their cohabitation, to blame her as Kristian does when talking to his colleague. They’re both guilty.

Besides hobbies, Alois also lacks self-confidence. When speaking to the director of the travel agency (Jaroslav Marvan), he only nods resignedly and nervously plays with his fingers. He doesn’t have the courage to speak up. If he comes across as worldly as Kristian – it will be in Men about Town (Světáci, 1969), in which Nový, after several futile attempts to make a sequel, at least partially revives the legacy of the iconic character – it is thanks to the aforementioned preparedness. He knows in advance what to do and what to say. He also has a set sum of money set aside for each evening. But outside the confines of the Orient Bar, where he is in control, he loses his confidence. Even in the role of Kristian. When he takes a taxi with Zuzana, he nervously watches the taxi meter with the increasing price of the ride, which he had not calculated in beforehand. He only has a measly 30 crowns in his wallet.

One of the most popular Czech comedies can thus be seen, with a slight shift in perspective, as the story of two insecure, unhappy partners who totally fail to communicate with each other openly. The husband assumes another identity to flirt with other women behind his wife’s back. The wife pretends that everything is fine while in reality, she is mentally devastated and plans to file for divorce. The husband’s reformation comes only after he becomes terrified at the thought of being left alone. More significantly, or more visibly, however, the wife is transformed in the finale, having in fact done nothing to compare with Alois’s secret dates. She just couldn’t express how much pain she was in.

However immorally Kristian acted, the greater demands are ultimately placed on his wife in their strikingly asymmetrical relationship. In this respect, Kristian did not merely represent the prototype of a new type of film lover – paradoxically in a character that is admittedly illusory, unreal, even impossible. In some ways, Kristian was also normative for the romantic comedy genre. To this day, domestic films of this genre follow a similar formula – leniency towards men, strictness towards women. Unfortunately, they are rarely as entertaining and charming as Kristian was.

Martin Šrajer