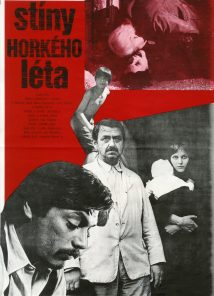

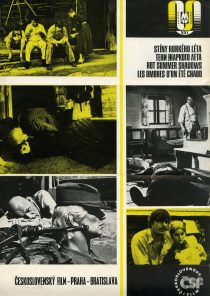

Two years after the war. A hot summer in the Beskid Mountains. A bird of brey circles above Ondřej Baran’s remote farm. The taciturn farmer takes a rifle and shoots the bird down. So far, he’s protecting only his livestock. But a couple of days later Baran, his wife Tereza and their two children will find themselves in danger. Baran’s farm becomes a refuge for five Banderites heading to Austria. The Ukrainian nationalists take the reticent farmer, his family and the local doctor hostage because one of them is wounded and unable to go on. A suspenseful wait for the next gunshot begins.

Jiří Křižan (1941–2010) first worked as a Mladá fronta editor and then became a dramaturge in the Barrandov Studios where he also edited dialogues for dubbing. After two collective projects, Shadows of a Hot Summer (Stíny horkého léta, 1977) was his first solo script. The story was inspired by one of the motifs in his novel Shadow (Stín). Křižan wrote the novel in late 1960s, but for political reasons it was published 8 years after his death (in the meantime, it was adapted into a film titled Silent Pain (Tichá bolest) in 1990). The book was inspired by memories (his own and witnesses) of the time after the 1948 Communist Coup.

In 1975, Křižan adapted the story to a film treatment and subsequently into a literary script. The story was co-authored by Zdenek Sirový who was logically considered as a suitable candidate for the director’s chair. But it wasn’t clear whether he would be allowed to return to directing after his previous film Funeral Ceremonies (Smuteční slavnost, 1969) ended up in a vault. František Vláčil, who worked for Krátký film back then, was in a similar position. Barrandov Head Dramaturge Ludvík Toman eventually approved Vláčil. This was in June 1976, too late to begin summer production. It was therefore postponed to the following year.

In the meantime, Vláčil made another film. Locations in Moravian Wallachia were scouted in parallel with finishing touches on his Fires on Potato Fields (Dým bramborové natě, 1976). As the main exterior location for his mountain ballad, Vláčil eventually chose the magistrate’s house in Velké Karlovice built in 1793 by carpenter Jan Žák and later renovated by Ján Bill. Other locations included Štramberk and Velké Meziříčí. Another important phase of preparations was the casting process.

As for the main role, Juraj Kukura was a perfect match for the weathered shepherd who seems a bit alienated in his environment. The ideal choice for Baran’s fragile and caring wife was Marta Vančurová. The casting of Banderites was, however, a bit delicate. At first, Vláčil wanted Polish actors. Perhaps because of his concern that the villains could be characterised by the Ukrainian language. In the end, he made use of the fact that the cutthroats don’t have a single line of dialogue in the film and decided to cast unknown actors from Czech theatres.

One of the was the 30-year-old Jiří Bartoška who had his hair bleached for the role. But according to the crew, it didn’t catch on and he had to wear a blonde wig. When Bartoška talked about the filming for magazine Záběr, he praised Vláčil’s direction: “Vláčil could simply describe the feelings of the characters we were supposed to play. Very accurately, thoroughly and knowledgeably. Before every take.” In addition to the hair dye and high temperatures, the crew had problems with the equipment. Cinematographer Ivan Šlapeta was forced to reshoot some scenes.

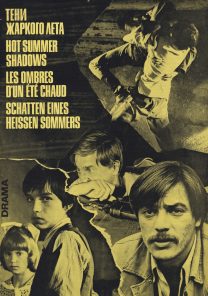

The first cut was finished in October 1977. But it took almost a year before Shadows of a Hot Summer entered domestic distribution. The premiere was postponed due to screenings at various festival, including the Karlovary Vary IFF, where Vláčil received the main award, the Crystal Globe (ex aequo with Soviet film White Bim, Black Ear). Thanks to the film’s festival journey, it received considerable publicity in Czechoslovakia and abroad, where reviews noticed mainly the usage of Western film methods and the ability to overlay the adventure framework with a psychological story.

Just like Vláčil’s older film, this contemplation about the nature of courage makes minimal use of dialogue. The tension is emphasised with sinister silence or Zdeněk Liška’s score (it was his last collaboration with Vláčil). But unlike Vláčil’s more poetic films, Shadows’ visual style is based on non-stylised realistic depiction of reality. An important visual element is the visualisation of the summer heat. Sharp contrasts of light and shadows, scorching sun and drops of sweat on the characters’ foreheads amplify the suffocating atmosphere. Still air, stopped time. Miroslav Hájek’s editing underscores the film’s slow pace.

This film, with which, according to some, Vláčil returned to his directorial debut, adventurous adaptation of a story by Rudolf Kalčík In Pursuit (Pronásledování, 1958), utilises a genre framework, but the genre isn’t a classical Hollywood Western film with gunfights and horse riding. For better or worse, Shadows of a Hot Summer come across as if you took a “waiting” scene from one of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns and turned it into a feature film.

From a contemporary point of view when we can draw a comparison to many suspenseful and dramatic home-invasion thrillers, the main quality of Shadows seems to be the psychological ambiguity of the characters. Baran may be portrayed as a placid man who avoids contact with people from the town where he goes to trade, but it’s not because he disdains violence, but because he wants nothing to do with other people. The question whether he can take action against intruder is answered at the very beginning. His problem isn’t cowardice as his son Lukáš assumes, but rather individualism. He learned to rely solely on himself and he expects the same from his offspring.

The driving force of the plot isn’t the tense situation, but rather the inner tension stemming from the conflict between the father and son. Normal activities at the farm carry on even after the Banderites appear. The family tends to their everyday chores so casually that it’s easy to forget they’re held hostage by invaders armed with guns and knives. We know how dangerous they are only from the dialogues explaining that the Banderites don’t care about anything and are capable of everything. It’s Tereza who finds herself in the biggest danger as she’s the most attractive prey for the Banderites. Her only task is to take care of the baby and the household and fend off attempts to get raped. She is repeatedly saved by Baran. Tereza is a fragile, frightened character without any opportunity to affect the plot.

This dramaturgical redundancy corresponds with the way Baran perceives, or rather ignores her. The protagonist focuses mainly on their son and, in the face of a foreboding tragedy, tries to teach him as much as he can – how to fix the roof, mow the grass, attend to the sheep – and prepare him for the future in which he will probably have to take care of his mother and little sibling. Serious matters such as the presence of the intruders are discussed with the doctor. During the entire runtime, Baran only rarely talks to his wife, only assures her that everything is going to be fine when she confides in him that she’s scared to death – a thing we can tell from her every move and look. And even through Baran evidently cares about the safety of his loved ones, the film repeatedly accentuates his “cowboy-like” solitary nature. Whether it’s through the unwillingness and inability to fit in the community or aerial views of the hero alone in the nature. He lives according to ancient customs, in harmony with nature, which on one side makes him noble but on the other side vulnerable. Sometimes, true heroism isn’t plucking up the courage to take the shot, but rather asking for help. The balladic tones of the film’s closing minutes are rooted in the doubts whether Baran acted correctly under pressure and left his son with a legacy leading to gradual eradication of the violent legacy of the war.

Martin Šrajer

Literature:

Petr Bedna, Jiří Bartoška. S rolemi je to jako s počasím. Záběr: časopis filmového diváka 14, 1981, no. 14 (4th September), p. 8.

Miroslav Courton, Dramatická balada o hrdinství. Nový český film Stíny horkého léta. Kino 33, 1978, no. 33 (30th May), p. 7.

Petr Gajdošík, František Vláčil – život a dílo. Příbram: Camera obscura 2018.