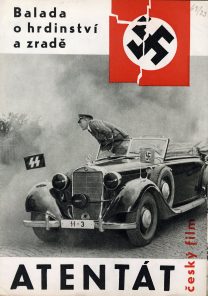

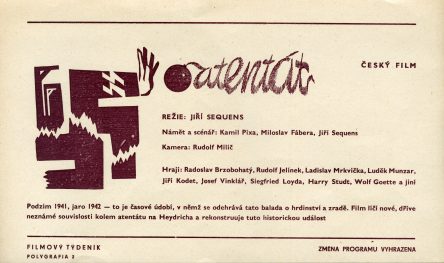

Jiří Sequens’ 1964 film The Assassination was the first Czech film attempt at adapting the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich for the big screen. Already during the war, Hollywood adapted the events surrounding the assassination of the Reich-Protector – in a very embellished manner – in films by Fritz Lang (Hangmen Also Die, 1943) and Douglas Sirk (Hitler’s Madman, 1943). Jiří Sequens, on the other hand, strived to achieve as accurate a depiction of reality as possible. To this end, he used detailed historical knowledge at his disposal at the time, including primary sources stored in ministry archives and direct eyewitness reports.

The first version of the script was created in collaboration with Miloslav Fábera and Kamil Pixa in spring 1959. The script originally called Operation Cannibal (Operace kanibal) was, however, turned down. It was subsequently reworked twice and finally approved in September 1963. Its authors placed the paratroopers’ mission in a wider historical context formally divided into several plotlines running in parallel: Operation Anthropoid itself, London-based Czechoslovak resistance, and the conflict between Heydrich and Admiral Canaris. The film also singles out the key dramatic plot built around the traitor Čurda (in the film, the characters use their codenames). All plotlines intertwine at the very end of the film culminating with the scene depicting the shootout between Gestapo and the Heydrich’s assassins hiding in an Eastern Orthodox church on Resslova Street. Sequens also transferred the efforts to achieve a faithful depiction of the events from the pages of the literary script to his directorial concept. The film was shot from February to mid-October 1964 mostly on location in Prague, Chrudim and in the Central Bohemian countryside. Extensive sets were built in the Barrandov and Hostivař studios for scenes taking place inside the church and its crypt, flooded by the Nazis during their attack. Sequens used archival photographs to build the set and allegedly went so far as to pay attention to exact positions of characters and vehicles in the scenes.

The film’s civil tone stems also from the minimalist physical performances (Radoslav Brzobohatý, Rudolf Jelínek, Ladislav Mrkvička, Jiří Kodet) and laconic dialogues filled with military jargon. For that matter, the overall austerity is indicated already in the opening credits displaying only the surnames of the actors and crew.

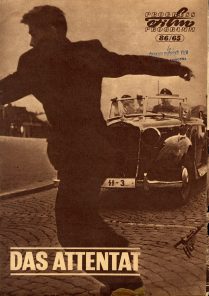

On the other hand, Sequens didn’t hesitate to use fully stylised genre techniques to add to the film’s suspense and its emotional effect on the viewers. For example, the scene of the assassination itself is built according to the principles of classical gangster and western films and uses careful analytical editing, point-of-view shots and suspense-increasing details. Cinematographer Rudolf Milič (The Devil’s Trap, Accused) also occasionally digressed from the film’s prevailing quasi-documentary style – for instance, in chiaroscuro night sequences and dialogue passages dynamically staged in width and depth thanks to a combination of widescreen format with short-focus lenses.

After its premiere in August 1965, Assassination attracted a significant number of viewers (almost 1.5 million). Also the reviews were favourable. But historians had some reservations about certain digressions from reality. Their objections concerned mainly the insufficiently explained role of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, a unilaterally depicted reception of the paratroopers by Czech people, and the suppression of the real motivation of Karel Čurda’s betrayal, as summarised by historian Karel Bartošek in Film a doba. According to him, this created a paradox when a film striving for authenticity eventually ended up – because of certain flattening – being less dramatic than reality.

“It is not my task to look for causes even though I feel that the desire for outer attractiveness at times prevailed over the inner attractiveness of this big subject,” concluded the article’s author.[1] It should be noted that filmmakers who tried to adapt it later on got carried away by this desire even more.

In addition to a positive reception at home, the film also enjoyed success abroad. It won two prestigious festival awards (Golden Prize in Moscow and the main award at the Thessaloniki Film Festival) and was sold into many countries including big distribution markets such as France, Italy and Great Britain. It was also involved in a curious situation – before its official screening in Helsinki, the film was seen by Heydrich’s widow. “She didn’t comment on its content in any way. But who else would be better suited to comment Sequens’ Assassination and the person of the SS-Obergruppenführer and General of Hitler’s Police Reinhard Heydrich than Linda Heydrich herself?” asked the head of the dramaturgical group Bohumil Šmída in his memoirs.[2]

Jan Křipač

Notes:

[1] Karel Bartošek, Atentát jako dokument? Film a doba 11, 1965, no. 8, p. 441.

[2] Bohumil Šmída, Jeden život s filmem. Prague: Mladá fronta, 1980, p. 224. Jiří Sequens recalled that this occurred in Oslo – see The Making of the Assassination (Spěváček family, 2006) on the DVD published by Bontonfilm in 2007.