The screening of Ikarie XB 1 as part of the Cannes Classic presentation was not the first opportunity foreign audiences had to see the admired Czechoslovak sci-fi on the silver screen.

The card on which the foreign travels of Ikarie XB 1 have been recorded shows that in addition to countries of the Eastern Bloc, such as the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Bulgaria and Cuba, this representative of Czechoslovak science fiction also visited a number of countries in the West. Moreover, the first country outside the socialist bloc to ask for a copy was Japan, where Ikarie landed in mid-May 1963.

Less than three months after its domestic premiere in March 1963, the film made an appearance at the inaugural sci-fi film festival in Trieste, Italy (Festival Internazionale del Film di Fantascienza). Sharing the top spot with Chris Marker’s La Jetée (The Pier), Ikarie XB 1 returned from the festival with the Golden Rocket award (which subsequently was only delivered to director Jindřich Polák via Prague’s Film Club in September).

Even before the results were announced at the festival, Italian film critics expected Ikarie to scoop the top prize. And with reference to another two sci-fi movies from the same country of origin (Kybernetická babička [Cyber Granny], 1962), and Muž z prvního století [Man from the First Century], 1961), the press even wrote about the revival of the genre in Czechoslovakia. The certain earnestness and psycho-sociological message of Ikarie placed it ahead of the other two Czechoslovak entries. Enthusiastic critics described it as a work of a moral dimension and great symbolic values that “deserve to compete at a level well above the other films entered at this festival.” [2]

One member of the festival jury was Umberto Eco, 31 at the time, who spoke to Corriere della Sera about Ikarie XB 1 and the other two Czechoslovak entries in Trieste:

“Czechoslovak films Muž z prvního století and Ikarie XB 1 strike a perfect balance between carefully crafted utopia and a natural human sense. It is also worth giving a fleeting look to both films’ attempts to smuggle in some odd cultural tendencies: in the former the creators present their idea of a socialist society, established along the lines of our avant-garde art, a civilisation designed by Bruno Munari and his disciples, proponents of ‘programmed art’. What we see in Ikarie on the other hand, is most likely an ‘atomic twist’ danced by cosmonauts in their spaceship’s lounge area. But there is also poetry represented at the festival such as in the country’s third entry, Kybernetická babička, created by none other than the famous Jiří Trnka.” [3]

Il Piccolo also heaped praise on the film, appreciating its high technical quality (perhaps with the exception of the costumes, labelled “naïve”) and realistic depiction of everyday life on board a spaceship. It likened the film’s sweeping narrative to novels by Jack London and Joseph Conrad. By way of conclusion, the author voices their belief that Ikarie XB 1 was “one of the best science fiction films released in recent years.” [4]

Another journalist who watched Ikarie in Trieste was an editor of UK’s Financial Times. They called attention to the theme of the film, which years later became the starting point for the incomparably better-financed Interstellar, directed by Christopher Nolan: “What is more, Ikarie brings to the table something that may one day become one of the serious issues of estrangement: what happens to two people when she stays behind on Earth and ages 15 years while he ages a mere 18 months in those 15 years spent flying through space?” [5]

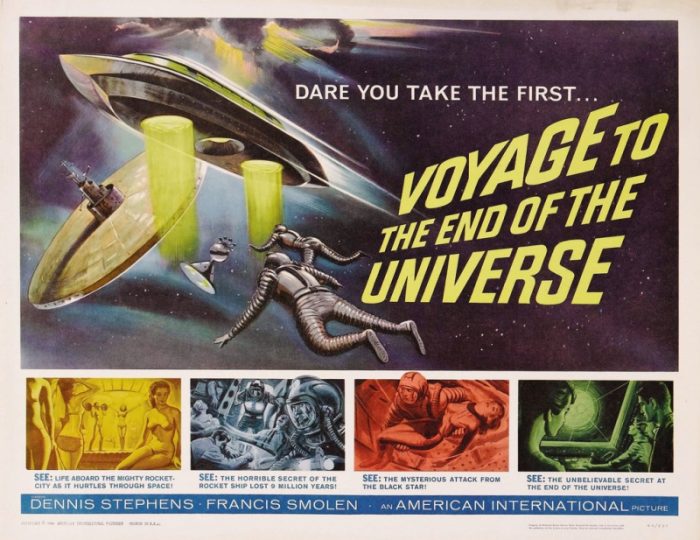

In January 1964, a 10-part wide-angle copy was sent to the USA to be distributed in the country by American International Pictures, a company owned by B movie producer Roger Corman. AIP adapted Ikarie XB 1 for US audiences, something that was regularly done with other not so dynamic eastern European sci-fi films, such as Soviet Planeta Bur (1962, released in the US as Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet). Ikarie XB 1 was cut to 65 minutes and was renamed to Voyage to the End of the Universe. It was also heavily edited and dubbed in English (with characters obtaining English names).

In the American version, space travellers are looking for a green planet, instead of a white one. In an added closing sequence, the crew find their desired destination when they behold the Statue of Liberty from the spacecraft’s window, anticipating the surprising ending of Planet of the Apes (1968). There has been speculation that besides the screenwriters for Planet of the Apes the US version of Ikarie also inspired John Carpenter when he created his sci-fi comedy Dark Star (1974), which presents a satirised view of boredom experienced during extended space flight.

The hobbled API version of Ikarie XB 1 was for a number of years screened in cinemas and on TV in many other countries making it for quite some time the only version known to Western audiences. The situation was rectified only in 2004 when the Czech Centre in New York put on a travelling retrospect of Pavel Juráček’s work that included Bláznová kronika (Jester’s Tale, 1964), Koncem srpna v hotelu Ozón (Late August in Hotel Ozon, 1967), Případ pro začínajícího kata (Case for the New Hangman, 1969) as well as the unabridged version of Ikarie XB 1, complete with the original soundtrack (obtained from a copy loaned by the NFA). Titled “Pavel Juráček: New Wave Master Rediscovered”, the Czech Centre show was launched in early March in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. It lasted until August when the films were screened by Hollywood’s American Cinematheque at the Egyptian Theatre.

In February 1965, John Stapleton, a representative of the British Film Producers Association, and Peter Baker, editor-in-chief of Film and Filming, made the trip to Prague with the aim of selecting suitable candidates for a Czechoslovak cinema overview at London’s National Film Theatre planned for early summer of that year. Ikarie XB 1 did not fail to catch their attention. Just like the majority of the selected films, Ikarie was screened twice in London.

A note on the London film show reported on Polák’s sci-fi movie as follows: “(…) a very imaginative film, devoid of propaganda, and as scientifically accurate as possible. The pace is slow but the story is absorbing, and the human beings behave in a credible way.” [6]

In early 2006, Czech and foreign fans of science fiction movies were delighted by the first ever release of Ikarie XB 1 on DVD. Filmexport Home Video provided subtitles for the DVD, making the film accessible to viewers for whom Czech is not a native or acquired language. One such viewer wrote an insightful review on the DVDtalk website, touching, among other things, upon the differences between the original and US versions:

„The original Ikarie XB 1 is a much different experience than Voyage to the End of the Universe. American-International altered the story to make the spaceship an alien craft from an unknown planet. The American dub described the voyage as a one-way pioneering trip. Although we recognise the derelict spaceship as being from Earth (the playing cards, numbers written on the bulkheads) the voyagers theorise that it’s a ‘primitive craft’ from some unnamed warlike civilization.” [7]

A new digital transcription of Ikarie XB 1 was created in 2013 by UK company Second Run. The disc also includes an interview with film critic Kim Newman and the booklet features an essay by film historian Michael Brooke. It points out, among other things, what Stanley Kubrick borrowed in terms of style for his cult sci-fi movie 2001: Space Odyssey (1968). [8]

In addition to Italy, the USA and UK, Ikarie XB 1 was also purchased for distribution in Belgium, Cyprus, Switzerland and Canada (a Week of Czechoslovak Film was held in Ottawa in 1966, mirroring an earlier event of the kind in London). Ikarie entered distribution in almost 40 countries and it keeps acquiring new fans even though it is decades since it was made. It is safe to assume that more will follow now that Ikarie XB 1 has been included in Cannes Classics, a festival category that has previously reintroduced such timeless works of world cinema as The African Queen (1951), Psycho (1960) and Il Gatopardo (1963).

Notes:

[1] Kybernetická babička won the Golden Seal at the festival although at least one journalist writing for Giornale del Mattino considered it worthy of the main prize. See Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1963 [Czechoslovak cinema in the foreign press], issue 9, p. 15.

[2] A review in Bianco e Nero. Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1964, issue 1, p. 10.

[3] Report from Trieste film festival. [1963]. BSA, SCE, film: Ikarie XB 1.

[4] Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1963, issue 9, pp. 13-14.

[5] Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1964, issue 2, p. 16.

[6] Czechoslovakian Film Week. [1965]. NFA, ÚŘ ČSF, R5/AI/1P/7K.

[7] Erickson, Glenn, Ikarie XB1. DVDtalk: http://www.dvdtalk.com/dvdsavant/s1867ikar.html

[8] For more information on the disc see: http://www.secondrundvd.com/release_ikarie.php